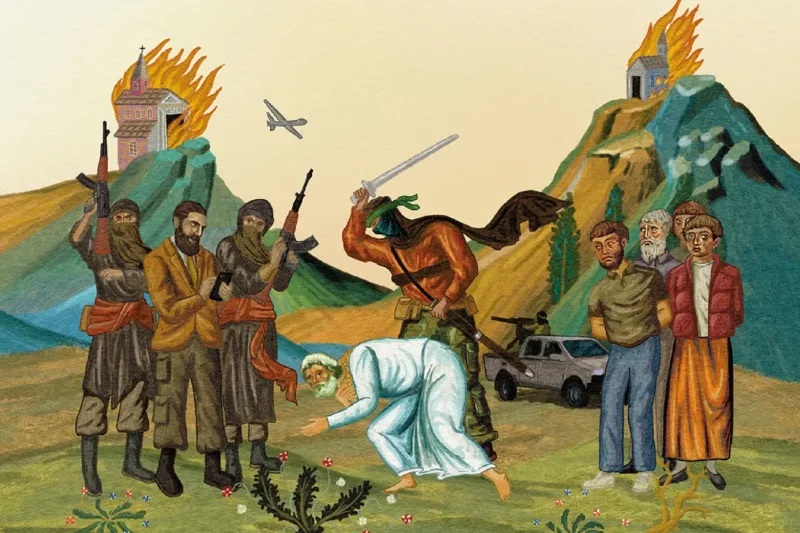

In the rush to declare Isis dead now that its caliphate has been routed from Iraq and Syria, it’s easy to forget that its Nigerian fellow traveler, Boko Haram, is still going strong. April’s five-year anniversary of the Chibok schoolgirls’ kidnapping, for example, passed with barely a celebrity tweet to mark it, despite the fact that 112 of the girls are still missing. Nor is much fuss likely to be made next month, when an insurgency that has killed nearly 30,000 will enter its second decade as violent as ever.

Out of sight and out of mind, Boko Haram’s power is growing. And to find out why, all you have to do is follow the children who beg on the streets of Nigeria’s northern cities.

Any visitor to Maiduguri, for instance, will soon find themselves surrounded by pitifully young kids tugging at their sleeve, begging for money. Cross a dusty palm with a 50 naira note (about 10p), and they’ll usually go away. The liberal guilt trip, though, should stay with you. Because in paying up, you’ve also just indirectly subsidised Boko Haram.

The street kids haven’t been sent out by some desperate parent whose poverty outweighs their scruples, or even some local Fagin gangmaster. Instead, the trail leads to the local madrassas, or Islamic boarding schools, of which there are scores in Maiduguri, and thousands across north Nigeria. Officially, these madrassas provide religious schooling for children whose parents either can’t afford western education or don’t want it. In practice, they function as Dickensian-style poorhouses, with conditions that even Mr Bumble, the poorhouse beadle in Oliver Twist, would baulk at.

Children as young as five can be left in a madrassa, but there’s often not even enough money for food. Begging, therefore, is as big a part of the timetable as rote-learning of the Qur’an, and children spend several hours on the streets each day.

Traditionally, this was justified as a form of almsgiving. By handing over a few naira to the madrassa pupils, who are known as almajiri, or ‘travelers in search of religious knowledge’, fellow Muslims could indulge in a spot of Islamic virtue-signaling. But thanks to Nigeria’s population explosion, the sheer number of almajiri has overburdened the public’s charitable instincts. There are now an estimated ten million nationwide — far more beggars than a country as poor as Nigeria has patience for. As a madrassa teacher in Maiduguri once told me, these days his students are as likely to be given a beating as a 50 naira note. ‘I have lost count of the times my pupils have come home with arms or legs badly hurt,’ he said. ‘They’ve even been knocked unconscious.’

This is where Boko Haram comes in. Having millions of alienated, half-starved young boys on the streets provides the Islamists with a potentially limitless recruitment pool. Many already come half–indoctrinated, thanks to the hardline, Saudi-influenced religious dogmas peddled in the madrassas. And for others, a few hundred naira is often enough to win them over, especially if it gives them a chance to inflict violence on the society that no longer looks after them. Indeed, it’s no coincidence that many of Boko Haram’s senior leaders are ex-almajiri: Abubakar Shekau, the cackling psycho behind the Chibok kidnappings, enrolled in one as a boy. Some almajiri are also groomed into the ranks of Boko Haram’s legion of child suicide bombers, three of whom killed 30 people in a village outside Maiduguri two weeks ago.

Nigeria’s government has belatedly woken up to the dangers posed by the almajiri system, aware that it also puts children at risk from other criminal influences: street gangs, sex abusers and slave traders. Yet little real progress has been made. Nigeria’s previous president, Goodluck Jonathan, pledged hundreds of new schools for the almajiri, noting that many had become ‘cannon fodder’ for the terrorists. However, many of the new facilities have either crumbled into disrepair or have never been properly used. Aid agencies are wary of speaking out about the problem for fear of being seen as anti-Islamic. Meanwhile, the numbers of almajiri continue to rise. Because the insurgency is still raging in rural areas, many parents think their kids are safer being packed off to a madrassa in a local town, unaware of the risks to their children.

Father John Bakeni, a Christian pastor, has seen how quickly youngsters can turn semi-feral. A few years ago, he was posted to Gashua, a town close to Nigeria’s northern border with Niger, where most of the 3,000-strong Christian community had fled because of Boko Haram attacks. During his time there, he buried four murdered parishioners, and saw his flock dwindle to just 200. What made the experience a real test of his faith, though, was the constant harassment from gangs of almajiri, who would hurl stones and dead animals into his compound, and shout: ‘Infidel, we will kill you.’

‘It was very tough psychologically — someone was clearly putting them up to it to try to drive us out,’ says Father Bakeni, who is now based in Maiduguri. ‘Unfortunately, the almajiri system has become a way for parents to relieve themselves of their responsibility for their children. A lot of the kids, if you asked them where home was, they couldn’t even tell you.’

Once again, this is a taboo that western aid agencies are ill-equipped to address. Most do not feel comfortable lecturing Africans, especially Muslims, on family responsibility. Nor are they likely to tell local Muslim men to stop taking multiple wives, a practice which is blamed for creating large numbers of children whom they cannot afford to look after. Instead, the main figure who has spoken out is a Muslim himself: Muhammad Sanusi II, the modernizing emir of the northern state of Kano. He wants a new system where fathers without financial means would be banned from taking more than one wife. ‘Those of us in the north have all seen the economic consequences of men who are not capable of maintaining one wife marrying four,’ he says. ‘They end up producing 20 children, not educating them, leaving them on the streets, and they end up as thugs and terrorists.’

His Highness is used to saying the unsayable. In his previous job, as head of Nigeria’s Central Bank, he blew the whistle on a $20 billion fraud in the state oil industry, allegations which carried all the more weight because he was seen as one of the few competent people to have held the post.

Whether anyone listens to him, though, is another matter. He was promptly sacked for his whistleblowing activities. And in challenging the almajiri system, he is challenging not only Nigeria’s Islamic religious establishment, but the interests of Nigeria’s mafia-like northern politicians, who also use almajiri as street muscle.

‘With politicians also relying on the almajiri, I don’t think there is the political will in northern Nigeria to sort this problem out,’ says Father Bakeni. In other words, a problem that is quite literally begging for a solution seems unlikely to get one.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.