‘The Spectator, having quite recently been a very bad magazine, is at present a very good one.’ Those gratifying words began a full-dress leading article in the Times on September 22 1978, headed ‘On the Side of Liberty’. Its occasion was this magazine’s sesquicentenary, which we celebrated with a grand ball at the Lyceum Theatre, and much else besides. Although I can’t possibly be objective, I think that the praise was deserved. The revival of The Spectator 40 years ago was wonderful: it assured what had been the very insecure future of the paper, and it was the time of my life.

Founded in 1828 by the Dundonian Robert Rintoul to promote the cause of Reform, by the late 19th century The Spectator had become Liberal Unionist under the almost 40-year editorship of John St Loe Strachey, ‘pompous, pretentious and futile’ in Lloyd George’s derisive words. Then, in another long reign from 1932 to 1953, Wilson Harris made The Spectator what A.J.P. Taylor called a voice of ‘enlightened Conservatives’. By the time I discovered it as a schoolboy in the early 1960s, The Spectator was enjoying a purple patch, thanks to Ian Gilmour, who had bought the magazine and edited it himself for some years, promoting his own brand of liberal Toryism while assembling some excellent writers. But he sold The Spectator to a shady businessman in 1967, and over the next eight years it went fast downhill, low in tone, hysterically Europhobic, shedding three-quarters of its circulation and by no means sure to survive.

Then came the miraculous rebirth, credit for which, as the Times rightly said, went to ‘Mr Alexander Chancellor, its still new editor, and Mr Henry Keswick, its still new proprietor’. Sir Henry, as he now is, bought The Spectator in the summer of 1975, and installed Alexander, possibly because he was the only journalist he knew, even though Alexander had worked for Reuters and as a television reporter, but never for a paper, daily or weekly. It proved an inspired choice. While The Spectator moved from 99 Gower Street to 56 Doughty Street, close to Dickens’s house, Alexander found himself like a manager who takes over a faltering football club and has to reshape the team.

Some survivors of the previous regime went on writing for us. Bryan Robertson, a delightful old queen who’d had a distinguished career as curator of the Whitechapel Gallery, wrote one of the unlikelier pieces for our arts pages on ‘Punk Rock and the Sex Pistols’, while Peter Ackroyd also stayed on, and once a week could be just about perceived in a corner of the editor’s office through the pall of cigarette smoke (Alexander smoked 80 a day, alas), turning out an impeccable 900-word film review in an hour.

But others were more or less gently shed, as Alexander picked his own people, some of them old friends, such as Simon Courtauld as managing editor and John McEwen as art critic. Years before, George Hutchinson had worked for the magazine, and was brought back as deputy editor to provide continuity, as well as his own kind of bohemian urbanity. My own brief and inglorious career in publishing had ended when I was sacked, and by pure chance I bumped into Alexander a couple of months later. After a bibulous evening, he offered me a job as assistant editor, and changed my life.

Our first star signing was Auberon Waugh, but finding a political columnist was a problem, and there were a couple of false starts, as well as a farcical episode when my friend Alan Watkins was hired but reneged when he was made a better offer. I’d have liked to have a go myself, but with his unerring instinct Alexander made a far better choice in Ferdinand Mount, while I became literary editor. After Taki joined us, one of my own picks on the team sheet was Jeffrey Bernard, whom I knew all too well from sundry dens in Soho, and so we hit on the double act of High Life and Low Life. If anyone ever needed a first-rate secretary to bring order to chaos it was Alexander, and he found one in Jenny Naipaul, wife of my dear friend Shiva Naipaul, who also wrote for us. And then we found the wonderful Clare Asquith, the one person from our team who’s still working for The Spectator today.

To look back is exhilarating but poignant. Contributors to our 150th anniversary issue of September 23 1978 included Waugh, Richard West, Nicholas Davenport (the veteran City columnist), Peter Jenkins (the Guardian political columnist, whom I’d recruited as theatre critic), George Gale, Robert Blake, Nicholas von Hoffman and Henry Fairlie writing from America, and in the books pages Michael Foot on Silone, Anthony Quinton on Isaiah Berlin, Ian Gilmour on Jo Grimond, Watkins on Waugh, John Biggs–Davison on Ulster, Thomas Szasz on R.D. Laing, and Francis King. All of them are now gone, as is a former literary editor who generously offered his help: Graham Greene gave us the puff of puffs, calling The Spectator ‘the best-written magazine in the English language’.

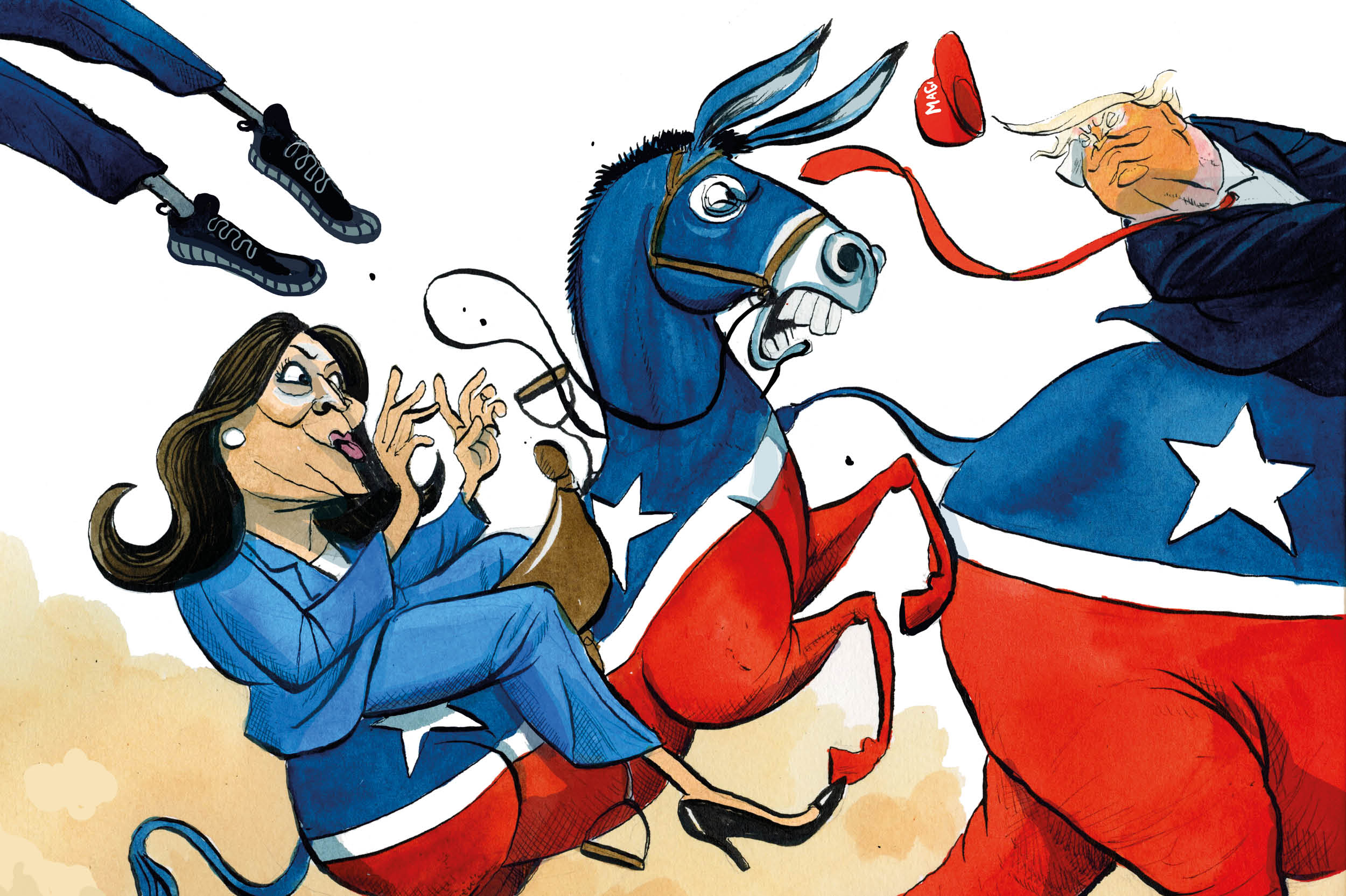

That other laudatory tribute, from the Times (in a leader unmistakably written by William Rees-Mogg, its editor), claimed that, ‘The Spectator now plays an important part in the most interesting intellectual movement of our time.’ What the New Statesman had been in the 1930s and 1940s in advancing the corporatist-collectivism which was to prevail for so long in British politics, said the Times, The Spectator had become to the new mood rejecting it. That wasn’t wholly wrong. A libertarian tone was set by Ferdy Mount, who later worked at Downing Street for Margaret Thatcher, by Bron Waugh, although his own brand of Tory-anarchism took the form of contempt for all politicians, including Thatcher.

But if the Times was flattering, it was also misleading. No magazine edited by Alexander was ever going to be doctrinaire. He had never voted Tory before he became editor, and he was no kind of ideologue. Closer to the mark was the American journalist Michael Kinsley when he said he loved ‘the bitter wit… that makes American journalism seem paralyzed by gentility, the jaunty undertones of self-mockery and unseriousness that run through The Spectator’.

Under Alexander’s almost effortless guidance it combined the grave and the frivolous. We had Jeff’s inimitable column and Dick West’s idiosyncratic foreign reports. But we also had Hans Keller’s fine translation of that most beautiful passage of German prose, Grillparzer’s oration for the funeral of Beethoven, and Colin Haycraft’s ode on the election of the Oxford Professor of Poetry, which commented wittily on the candidates in faultless Latin, with 14 echoes of Horace.

All this may sound cliquey, but a successful weekly is a club, with its private jokes and scandals, and its conviviality. There we really couldn’t be faulted. The sesquicentennial ball was merely the high point, with le tout Londres sipping and bopping, and marked by a violent altercation between two women journalists which led to a libel action, mercifully not concerning us, although we had our share of those. Then there was our summer party, and the lengthy Thursday lunches. Sometimes we had American visitors, from Spiro Agnew to Alger Hiss, sad to say not on the same occasion. Agnew’s fellow guest was Barry Humphries, who, toward the end of lunch, left the room. After a remarkably short interlude, Dame Edna entered, to the consternation of Agnew.

Many years later, when Kingsley Amis’s letters were published, it transpired that after visiting the office he’d written to Robert Conquest to say that, ‘Six of them came into the boardroom where I had been trying to read back numbers and each opened a bottle of wine. I don’t know how they bring the paper out.’ That really did take me aback: crikey, if Kingsley had thought we drank a lot… but then we did somehow manage to bring the paper out.

Reading John Preston’s book A Very English Scandal and watching the equally enjoyable television adaptation, with Hugh Grant’s brilliant performance as Jeremy Thorpe, reminded me that it was in that sesquicentennial year that the Thorpe affair leapt into the headlines and our pages, with Waugh, Mount and Christopher Booker all writing about it in different registers — and not just our pages. Our local, or alternative office, was the Duke of York in the mews opposite, where Dave Potton — still ducking and diving, I hope — was our genial host, and a repository of Cockney humor. One day when I looked in rather early, he greeted me: ‘Tell me, Geoff, why is Jeremy Thorpe like William the Conqueror?’ ‘You tell me, Dave.’ ‘Cause they’re both fuckin’ Normans.’

If Henry Keswick hoped that his generosity would be recognized by the Tory party, he was sadly wrong, while for all that praise the circulation stubbornly refused to shoot up (that was to come later), and the only thing that mounted was losses, until Henry understandably tired of them and sold The Spectator. In 1984 Alexander was removed. Now he is the saddest loss of all. At his funeral in early 2017, Craig Brown observed that Alexander was a wonderful editor, even if those of us who worked for him could never quite work out why. In his indefinable way, as an animating genius, he was the best editor I’ve ever known, and he really had made The Spectator ‘a very good magazine’.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.