South of France

Scotching my bright idea of a stiff gin for Dutch courage in the bar across the road, Catriona bounded straight for the door of the Colombe d’Or. My restaurant phobia was fast upon me, and I followed her into the bourgeois holy of holies more slowly than a nudist climbing through a barbed wire fence.

We were half an hour early and directed to the bar. Here my plea for strong spirits was again denied, and I had to make do with Champagne. Speechless with ecstasy — this was her birthday treat — Catriona toddled off with her flute to cast her eye over the Miros, Matisses and Chagalls in the dining room. I sat alone on the windowsill in the bar where Picasso and Yves Montand and James Baldwin had once parked their famous asses and I mourned.

A northern English couple came in and swapped serene platitudes over their Champagne flutes. Another couple arrived, also English. He had the huge head and pendulous earlobes of a captain of industry. He rather thought Champagne would be the thing, she gin. She gave way and they had Champagne. Tuesday night, I thought, in a hilltop village restaurant above Cannes during a world pandemic and the place is full of English necking Taittinger.

Catriona, now solemn with reverence for the art she’d seen, returned to the bar for another glass. We could smoke by the pool, she had found out. So I followed her to a seat next to a green swimming pool, and we sat and looked at the water and the surrounding artworks and silently smoked.

An elderly woman came past, propelling herself on hiking sticks. She was a very English, no-nonsense, wholly admirable Lady Circumference type. ‘Damn,’ she said to a pink-faced man in pink trousers following four paces behind. ‘Johnnie, I’ve left my bloody mask in the room.’ Johnnie harrumphed good-naturedly and tottered off to fetch it. ‘He doesn’t care about masks,’ she said, noticing us. ‘I do. I’ve had it.’ While Lord Circumference was away, she pointed her sticks at this and that sculpture or mosaic and rattled off the artists’ last names — Chagall, Calder, Braque — in a tone of voice suggesting that it was all rather regrettable.

At 7:30 we went into the garden and were shown to a table next to a 4ft-tall ceramic thumb and given laminated canteen menus. All the other customers seemed to surge in at once. From the wine waiter Catriona ordered a bottle costing more than my last car. I tutted and shook my head. ‘You could buy six boxes for that,’ I said primly. The wine waiter asked Catriona if she’d like a bigger glass. ‘Spot the lush,’ I said. ‘A bigger glass to let the wine breathe,’ she said with infinite patience. The only things I recognized on the menu were foie gras and turbot. So I had those. The foie gras was a brown doorstep laid on a thick white plate and nothing else. ‘You want foie gras, matey? Here you go,’ the chef seemed to be saying. The turbot came peeled and filleted and all I had to do was shove the soft white meat into my gob in four mouthfuls. Between the third and the fourth I told Catriona that at Brixham fish market in Devon you could pick up a turbot the size of a trash can lid for a tenner and anything this size was thrown back.

And then I looked around me at the other diners for the first time and realized I had made a silly mistake. Lord and Lady Circumference; the platitudinous northern English; the captain of industry and his memsahib; and that elderly gay couple over there with the dog: everyone was bent over their plates and browsing and sluicing with quiet enthusiasm. We might have been in a McDonald’s. Because for all its art and famous clientele, the Colombe d’Or is in actuality nothing more than a sort of upmarket canteen. If I’d been paying attention instead of paralyzed by the chip on my shoulder, the laminated menu written in childish colors in a huge font would have given me a clue. Or the school-lunch dispatch with which the waiters got the food out. Or their harassed good humor. Or Lord Circumference’s napkin tucked into his collar and the side dish of fries he was eating with his fingers.

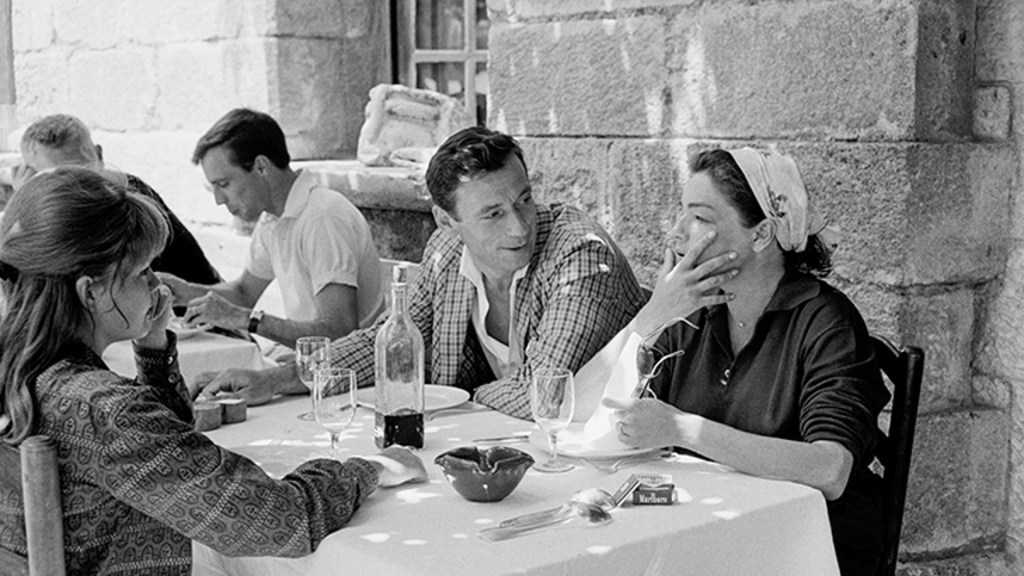

I went to the toilet, passing a large print of a sheep’s skull by Picasso. When I came back Catriona had pulled her chair up to a neighboring couple’s table and was chatting happily away to them as if she’d known them all her life. The garden terrace was now emptying as quickly as it had filled and I wondered if there was to be a second sitting. Meanwhile, I ordered a grappa, lit up a fag and better late than never — sorry, Catriona — I relaxed.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.