Laramie, Wyoming

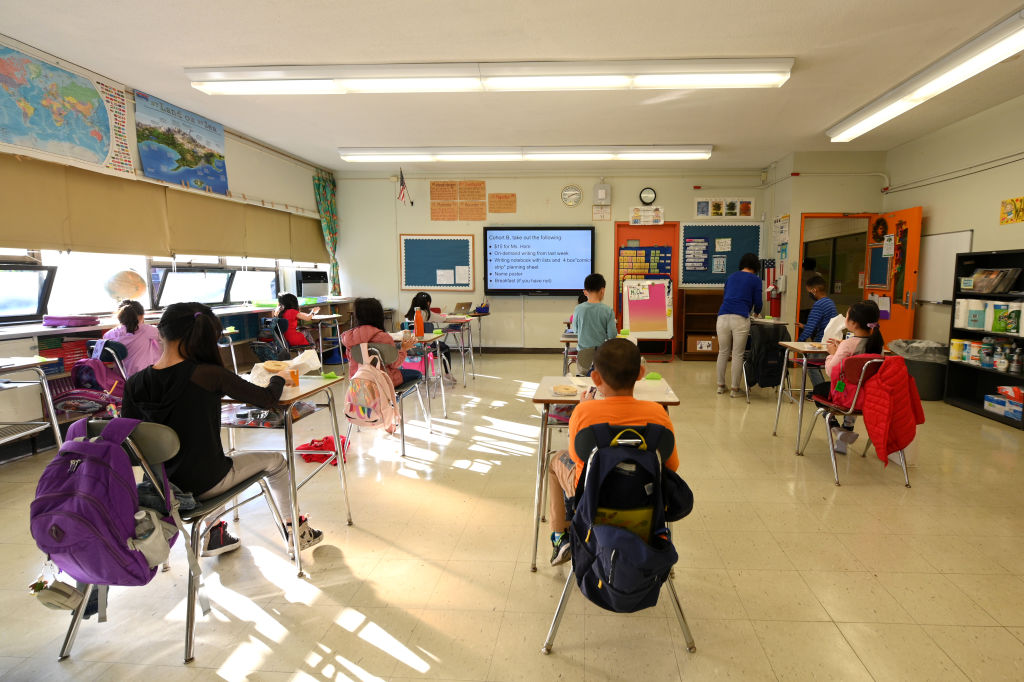

It used to be an axiom of America’s hard-driving, aggressive and acquisitive culture that ‘Those who can, do; those who can’t, teach.’ Over the past half-century it has become dreadfully plain to Americans, whether they abandon their children to the system of public education in the United States or not, that American teachers can no longer teach. This year, as the national teachers’ unions threatened to strike rather than return to their classrooms in the fall, their members admitted that they don’t really want to teach. Taken together, these facts give taxpayers no reason whatever to continue to support the educational profession, such as it is, in this country.

After that glittering commodity called money and the ghostly platitude that is democracy, Protestant Christianity and universal public education were the institutions most cherished by the American public from the birth of the nation down to the second half of the 20th century. Since then, the two have been joined in suicidal freefall toward a bottom whose depths have yet to be plumbed. The cause of the disaster is, quite simply, that the theological and intellectual demands of the churches and schools as they existed in the early days of the Republic were too strenuous to be agreeable to the majority of America’s clergy, pew-sitters, educators, children and parents of more recent times.

Their Puritan and Congregational ancestors, including the Deists among them, had been variously strict in their theological standards and also in their adherence to the intellectual rigor that reflected the high-mindedness of a morally and intellectually serious aristocracy. But aristocrats were in no position to ensure that criteria of excellence were enforced among the lower orders; and so, pretty early on, compliance with them began to weaken, as popular society and thought were progressively infected by the leveling democratic spirit that afflicted politics during and after the 1820s, when vox populi ceased to be the voice of the aristocracy reshaped downward during its transmission to We the People. Thus, as politics became more demotic, so did religion and education in America.

Still, American education retained some of its original integrity at the top of the system, and also at the bottom of it. The great universities of the Northeast and South continued to flourish, while, at the other end of the spectrum, education in rural America (which was most of it) and on the frontier, though simple, was mainly basic, honest and true. Public school faculties generally had little formal learning themselves, but what they did have was likely to be sound, much of it being historical and Scriptural; this they passed on to their pupils, with a success confirmed by the private journals and correspondence of the mid-19th century, among other such documents. Americans with an education worthy of the name could read to understand and write to be understood. In short, educators in that period knew less, perhaps, than what their contemporary equivalents know, but their knowledge was real knowledge, rooted in the realities of life and of the world that they were preparing their charges to confront, manage and live in. It was another case of less proving to be more.

Since John Dewey in the 1920s, progressive educators, obsessed with what the world should be rather than in interested in what it actually is, have been preparing children for a softer, gentler and more indulgent place by encouraging them to imagine that they are at the center of it. Thus education in the United States was transformed, for teachers as well as for their students, from a morally and mentally rigorous process that was also a plain and straightforward one into a mystery that only adepts, professionally trained in procedure rather than educated in substance, could comprehend, and in which ordinary people beyond the magic circle — including especially parents — have no business interfering. This mystification of pedagogy was associated directly with the advance of secular positivism, the rise of the public intellectual, the scientist, the ‘expert’ and the specialist, and the decline of the educated and cultivated non-specialist as a person worthy of intellectual respect.

It has also been the means by which the public-school teacher has sought to elevate himself to the exalted intellectual, social and financial status of the college and university professor. This ambition, alas, is an impossible one for the prodder of the dull sons of husbandmen, the keeper of the often violent products of the ghettos and the tentative coddler of the offspring of parents who financed and built the single-level brick-glass-and-plastic temples of learning in middle-class suburbs across the land. And so he looked in the opposite direction for his model of worldly success: the unionized working class. The result is the American Federation of Teachers and its lesser equivalents, whose members have succeeded in having it both ways: winning recognition as the cadet branch of the nation’s intellectual elite, and as members of the exploited and suffering industrial proletariat, the downtrodden but virtuous working classes.

The achievement might have been a lasting one. Instead it is failing and doomed to failure, for two principal reasons. The first is the public nature and ready availability of the compiled national educational statistics, which, when compared with those of numerous less wealthy and powerful countries, continue to demonstrate as they have for many years that America’s teachers can neither do nor teach. The second is the degenerate postmodern curriculum with which the pedagogical profession has replaced the traditional academic one, inculcating the principles of soft Marxism, rebellion and revolution, racism in reverse, sexual perversion, personal neurosis and a false, materialistic and corruptive metaphysics.

A worthy social experiment by a culture addicted to such exercises would be to tolerate a boycott of the schools by the AFT, allowing it to close them down for a period of, say, two years, after which a national evaluation would be conducted to determine how much of what the AFT and the media call ‘learning’ had actually been ‘lost’ to American children, and how great the resulting damage to the nation had been. We might then be in a position to decide whether our public ‘educators’ are essential, nonessential or expendable to society, or simply enemies of it.

This article is in The Spectator’s October 2020 US edition.