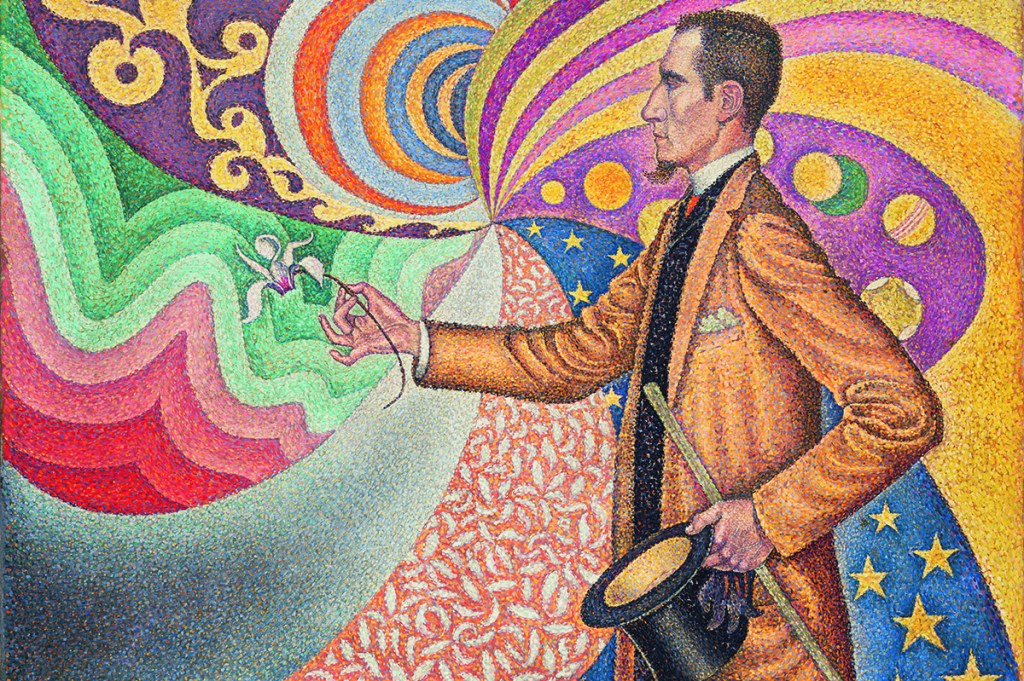

Paul Signac’s portrait of Félix Fénéon is a striking and historically important painting. But is it a good one? Its subject didn’t think so. Signac profiles Fénéon against a swirl of complementary colors and kaleidoscopic shapes, as if anticipating an acid-trip scene from a Roger Corman movie. This radioactively abstract background was bold stuff for Paris in 1890, when the picture was made, but contemporary critics disapproved, one finding the work ‘cold and dry’, another calling it ‘neither decorative nor comprehensible in terms of feeling’. Fénéon himself was similarly vexed by the final result, though he held onto the portrait throughout his life out of loyalty to his painter friend.

For those wondering just who this lanky fellow in the yellow topcoat is, Félix Fénéon: The Anarchist and the Avant-Garde — From Signac to Matisse and Beyond, now at the Museum of Modern Art, is an exhilarating introduction. A prescient critic, tireless editor, influential dealer and voracious collector, Fénéon (1861-1944) championed some of the most important painters of early French modernism, working to win these innovative but often unknown artists the recognition they now receive as canonical founders of the avant-garde. At the same time, he was an anarchist — probably of the bomb-throwing variety — who aspired to destroy the bourgeois institutions that seem to have been good to both Fénéon and the artists he loved. Just how Fénéon squared his aesthetics and his politics is a central concern of the exhibition’s curators, and with good reason: in many ways, the enigmatic Fénéon reflects the story of modernism in miniature.

Born in 1861 and raised in Burgundy, Fénéon excelled in school and moved to Paris after landing a cushy job at the war ministry. He was an excellent bureaucrat, but the enterprising twenty-something soon ensconced himself in the city’s literary, artistic and anarchist circles; before long he was founding magazines and moonlighting as an editor and writer. After an encounter with Georges Seurat’s ‘Bathers at Asnières’ at the Salon des Indépendants of 1884, Fénéon devoted himself to the cause of Seurat and other artists who seemed to offer a path out of Monet’s blink-of-an-eye Impressionism. These ‘Neo-Impressionists’, to use the term Fénéon coined in 1886, adopted the Impressionists’ divided brushstrokes and their interest in color’s optical effects, but in the service of a more permanent, classicizing image. Fénéon’s enthusiasm for Seurat’s frieze-like figuration — a ‘modernizing Puvis [de Chavannes]’, he said, associating him with the Symbolist and muralist — is vindicated in the numerous Seurats on display at MoMA: landscapes and portraits as well as a study for his acclaimed ‘Dimanche à la Grande Jatte’ (1884) and several excellent conté crayon drawings.

Signac, a colleague of Seurat’s and a fellow practitioner of pointillism (a word Fénéon himself never used but which has since become the popular term), fares less well. Whereas Seurat’s forms seem to coalesce and evaporate through the countless tiny dots that the painter so laboriously applies, Signac’s feel filled-in, as if he has drawn the lines first and then added the colorful dots via paint-by-number. It’s the difference between sensitive looking and surrendering to a formula. The result is a series of utterly unfeeling pictures — remarkably so, given their radiant hues. This is true for the lifeless portrait of Fénéon, but the bodies really start to reek when Signac hazards the monumental ‘Demolition Worker’ (1897-99), a shirtless abomination of proto-Soviet realism.

That Signac is a demolition man, and not a bricklayer, is relevant. Signac, like Fénéon, was an anarchist who believed in ‘propaganda by deed’, the idea that direct action can force society towards the beautiful and inevitable future. For a while, Fénéon believed that aesthetic formalism in painting might encourage a similar drive to autonomy in the viewer, by emphasizing the abstract ‘autonomy’ of the artwork. This hope was vital to his love for Neo-Impressionists like Seurat.Yet by the 1890s he seems to have lost some of his faith in art’s anarchist potential, and he turned more directly to politics.

‘Propaganda by deed’ also meant terrorism. With Paris beset by random acts of violence, the police began building files on Fénéon and his friends. After the posh Foyot restaurant was bombed in 1894, police found six detonators and mercury in his office at the war ministry. Fénéon, along with 29 others, was arrested. Joan Halperin, author of the definitive biography, argues that he was probably guilty. Seemingly unperturbed by a future engagement with the business edge of a guillotine, the workaholic Fénéon passed his four months in jail learning English and then translating Jane Austen’s Northanger Abbey into French. When the day came to take the stand, he wisecracked his way out of conviction:

‘It has been established that you surrounded yourself with Cohen and Ortiz,’ the prosecution charged.

‘One can hardly be surrounded by two persons; you need at least three,’ replied Fénéon.

He was acquitted for a lack of evidence, but the well-publicized trial was a bad look for the ministry. Losing his job, he was now free to devote all his time to the arts and was soon offered an editorial post at La revue blanche, then France’s leading ‘little magazine’ of the liberal arts. Within a year or two he ascended to the role of editor-in-chief. Under Fénéon’s leadership the journal published some of the great writers and poets of the fin-de-siècle: Mallarmé, Apollinaire, Oscar Wilde, Valéry, Verlaine. Claude Debussy was its music critic for a year, and painters such as Pierre Bonnard, Edouard Vuillard, Félix Vallotton and Henri Toulouse-Lautrec frequented the office. Their appreciation for Fénéon’s largely anonymous editorial efforts is evident in the two near-identical portraits by Vallotton and Vuillard of the goateed man hunched over his desk late into the night, readying some belatedly filed manuscript for publication at the eleventh hour.

La revue blanche folded for lack of funds in 1903, but three years later Fénéon made perhaps his most surprising move to date — to direct contemporary programming at the Bernheim-Jeune Gallery. Bernheim-Jeune (which only recently shuttered after more than 150 years in the business) was at the time one of Paris’s most prestigious galleries, but it dealt mostly in older, more conservative artists. Fénéon was brought on to bring fresh blood and avant-garde credibility to the shop. The anarcho-communist’s entry into the business side of art puzzled some of his friends, but others squared the post with the politics: ‘Fénéon, as a good anarchist, planted Matisses among the bourgeoisie from the back room at Bernheim-Jeune as he might have planted bombs,’ one fellow traveler remarked.

Looking at Matisse’s gorgeous ‘Interior with a Young Girl (Girl Reading)’, from 1905-06, it’s hard to believe that anyone could compare it to a bomb. Instead we might think of Matisse’s own, rather more comforting ideal for his paintings: ‘What I dream of is an art of balance, of purity and serenity, devoid of troubling or depressing subject-matter…something like a good arm-chair which provides relaxation from physical fatigue.’ A chief success of this exhibition is that it reminds us just how subversive and disorienting pictures such as this were for their initial audience.

Fénéon was a model Bernheim-Jeune employee for both clients and artists over nearly two decades, though privately he remained an anarchist to the end. His support was crucial for the early development of painters like Matisse, whom he signed to a lengthy contract in 1909, and Bonnard, who had regular solo exhibitions throughout Fénéon’s directorship. At MoMA, Bonnard is represented by four paintings, including a large double portrait of the businesslike proprietors ‘Frères Bernheim-Jeune’ (1920), on loan from the Musée d’Orsay, Paris.

The last section of the exhibition pulls examples from the Italian Futurists exhibition that Fénéon organized at Bernheim-Jeune in 1912. This succès de scandale was a signal moment in the avant-garde’s combative relationship with mainstream taste. Yet, compared to the treasures in the earlier galleries, it’s an unfortunately slack conclusion to the show. These Italians, dedicated as they were to speed, machinery and electric lights, were all about the future, but nothing seems so hopelessly dated now that we’re there and they’re past. No matter: let’s return instead to that stunning small Bonnard on the wall over there, whose placard says it was formerly Fénéon’s and is now in a private collection. Surely MoMA and these unnamed patrons won’t mind if I walk out with it under my shirt. I think oncle Félix would approve of the gesture.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s November 2020 US edition.