It’s of course premature to even speculate as to how the new administration will fashion a foreign policy. But enough declarations have been made to give an outline, so let us imagine the policies that might emerge.

The Founders never really envisioned foreign relations being a major preoccupation of America when they drew up the US Constitution. ‘Peace, commerce and honest friendship with all nations; entangling alliances with none,’ Thomas Jefferson famously admonished. In a document that brilliantly balances the government’s power and reach between executive, legislative and judicial branches, the executive is left with virtual control over making foreign policy, for little of that was expected.

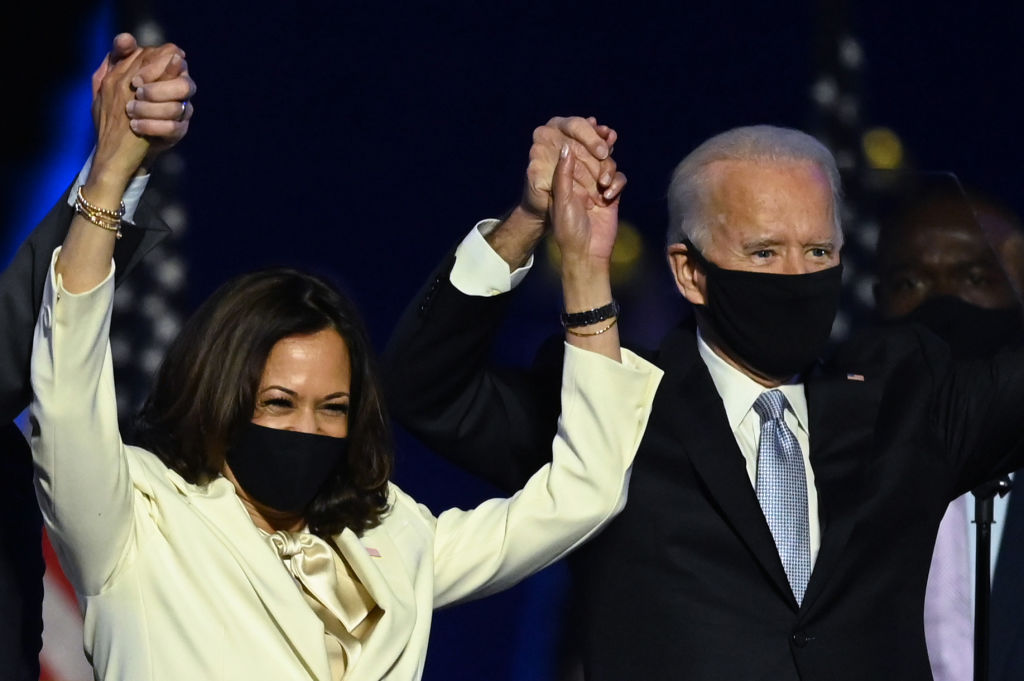

Moreover all branches of the US government resonate to the truism that ‘Personnel is policy’. This is particularly the case in foreign policy, where the president’s personnel choices effectively determine policy. The vice-president can also play a powerful, though opaque, role: in 2003 all of Europe assumed that Dick Cheney was the evil genius behind the Iraq War, despite his demurring.

So we really won’t know for certain until appointments are made for secretaries of state, defense and (now increasingly relevant) Treasury, along with the national security adviser. But statements from leading Biden foreign policy advisers and his vice-presidential pick Kamala Harris give us significant guideposts.

Anthony Gardner, an adviser to the Biden campaign and former American ambassador to the EU, has been mooted as a possible envoy to the UK. According to German news reports, he recently commented that Mr Biden would ‘prioritize relations with the European Union over the historic “special relationship” between the United States and the United Kingdom promoted by President Donald Trump’. A reporter present at Gardner’s talk had the impression that a declaration of support for the EU might happen ‘quickly, maybe on the first day’. This would be consistent with Obama’s admonishment on the eve of the Brexit vote that, were the British to opt out of the EU, they would find themselves at ‘the back of the queue’ when it came to a trade deal with the US.

It would also be consistent with Biden’s strong disapproval of Brexit. During the campaign, he promised to block a US-UK trade deal if Brexit led to a ‘hard’ Irish border. He probably resents Boris Johnson’s affable relationship with Donald Trump too. By all accounts, Number 10 will not find it smooth sailing in negotiations for a free-trade agreement with Biden, especially given how ready he is to use Ireland as leverage.

Having switched sides against one significant ally, it seems Biden’s vice president will advocate to quickly demote another. Kamala Harris recently promised that a Biden-Harris administration would ‘address the ongoing humanitarian crisis in Gaza, reopen the US consulate in East Jerusalem and work to reopen the PLO mission in Washington’. It seems team Biden-Harris were not impressed by the Trump-sponsored burst of peace-making between Israel and the UAE, Bahrain and Sudan.

Which brings us to the larger challenge the administration intends to pose to Trump’s foreign policy legacy: the Iran Deal.

Biden has made it widely understood that rescuing the Joint Comprehensive Plan of Action (JCPOA) is his foreign policy priority; reportedly, he feels it to be a critical legacy project. Biden has been selling the Iran deal since 2015, when he pitched Democrats in Congress to back it against Republican opposition in both Houses. Widespread concerns about the JCPOA’s verification protocols — from the UN’s IAEA, among other bodies — are unlikely to go addressed while Team Biden is struggling to get Iran back at the negotiating table. So confident are the Iranians of their new-found leverage that President Hassan Rouhani said recently that he believes the era of maximum pressure on Iran is over,’ according to Al-Monitor. No surprise that as of this writing they’ve refused the early overtures from Biden et al.

Given Israel’s assumed demotion in the line-up of allies, the Biden team will be shoulder-to-shoulder with Western Europeans who are heavily invested in developing Iran’s oil-refining and export capabilities. Israel has carefully chronicled Iran’s nuclear ambitions through 55,000 Iranian documents and a further 55,000 files on captured CDs that detail Tehran’s nuclear development programs. Further expansion of Iran’s long-range nuclear missile capabilities — which were not covered in the JCPOA — deepen concerns about the utility of the agreement. Many in Congress, and almost all of Iran’s neighbors across the Gulf, have growing concerns about this version of arms control whose advocates, ignoring Ronald Reagan’s advice, argue ‘Trust — but don’t bother verifying.’

The spate of recent (and surprising) agreements between the Gulf States, who have long been concerned about Iran’s military ambitions, and Israel — heretofore a sworn enemy — is likely rooted in the acknowledgement that Israel is the key military power in the region intent on countering Iran. These deals came together against the backdrop of a more aggressive US policy against Iran. Absent America’s commitment to challenge and contain Iran, these states may feel they’re going to have to make a deal with Tehran. They live in the neighborhood and Team Biden does not.

The craving to revive the JCPOA won’t go unchallenged by Congress, where Iran is unpopular on both sides of the aisle. Moreover the deal’s shaky record and the IAEA’s statements on Iran’s noncompliance will make Biden’s sales pitch that much harder. But the JCPOA was billed as an ‘agreement’ precisely to get around requirements that treaties binding the US must be approved by the Senate. So we can probably expect whatever new incarnation the agreement takes on will be similarly veiled. In any event, the reality is that Congress has little control over the President when it comes to foreign policy, short of declarations of war which require the approval of both Houses.

And then there is the genuinely outsized challenge of China. Biden has acknowledged the shift in US attitudes in recent years that has yielded a significant bipartisan cooperation in reining in Beijing’s trade practices as well as her growing military ambitions. Both sides of the aisle approve of Trump’s crackdown on Chinese spying and intellectual property theft, as well as the spectacle of Chinese professors and researchers being arrested and deported. Biden claims to be committed to the same vigilance, but says he will make this more effective as he’ll bring along US allies in this effort.

You wonders which allies he’s referring to. US allies in the Pacific have been sounding the tocsin on Chinese regional ambitions for years, and sought the Obama administration’s help in countering China’s new military bases on the Spratly Islands. Trump expanded military aid and cooperation with India in response to these same concerns, and even the Philippines — of late not fans of US military presence — have complained to various international bodies about Beijing seizing Philippine fishing vessels within their own waters. The Australians have been well ahead of Washington in recognizing the Chinese threat, especially in technology. They banned Huawei well before Washington did — an extremely courageous move, given that China is Australia’s biggest trading partner. Biden will indeed be ‘leading from behind’ if it’s these allies he’s thinking of.

But if it’s the Europeans — good luck. Western Europe’s dire fiscal situation has resulted in several countries signing up for Beijing’s Belt and Road infrastructure initiative. China has long cultivated (and remunerated) Europe’s political elites: investing in universities and offering lucrative incentives for supporting a few business deals on the side. In addition to ingratiating China among the political leadership, these decisions come down to cold fact.

What choice had the Port of Genoa but to accept Chinese investment? The EU has nowhere near the coffers required to bail out decrepit ports in the Mediterranean, and even less political inclination to do so for the periphery. The Chinese astutely observed this to be the West’s soft underbelly and have expanded their land-link ambitions and investments. Ursula von der Leyen, the president of the European Commission, recently warned of the risks to key infrastructure these deals have created, and voiced concern over the opacity and hidden companies behind the sale of prized European companies to the Chinese. But this is all a little too late. Europe’s fiscal crises have expanded considerably as a result of Covid, and America hasn’t sufficiently deep pockets to address its own infrastructure challenges, much less Europe’s.

[special_offer]

As for bringing allies along in US efforts to contain China, one is left to wonder about a suggestion made by Biden’s likely pick for defense secretary, Michèle Flournoy, to the effect that the US should have the capacity ‘to sink all of China’s military vessels, submarines and merchant ships in the S China Sea within 72 hrs’. Probably a good deterrent policy, but quite possibly not one likely to gain Western Europeans’ enthusiastic support.

Of surpassing importance in contemplating the new administration’s policy toward China will be the role of the supra-national investment community that has been flooding into China over the past two years, investing heavily in the major tech companies as well as in Chinese debt. This combination plays beautifully into Beijing’s plans, which are increasingly invested in a strategy of ‘technomic warfare’, as featured in Xi’s ‘China 2050’ plan. More than one titan of this international investment cohort has already been mentioned as Biden’s possible secretary of the Treasury, leading to speculation that any national security concerns brewing in Congress and the Defense Department will be overwhelmed by a push for a ‘China Reset’, to achieve a ‘win-win’ with Xi.

It’s quite possible that the very vocal anti-capitalist wing of the Democrats in Congress will raise Cain over the growing influence of these powerful financial interests. But given the vast expansion of US debt involved in printing money at the clip favored by the new monetary theorists, and the prospect of grim growth on the heels of COVID, the new administration could find itself investing in China at a clip. That might well be selling China the rope with which to hang us.