Mindfulness makes you smug. And not just mindfulness; a whole raft of alternative spiritual practices such as chakra cleansing and past life regressions feed a sense of superiority over normal mortals. That’s the finding of research from Radboud University in Nijmegen in the Netherlands involving some 3,700 people. The leader of the research, Professor Roos Vonk, first engaged in this field of study when she found that a boyfriend who went on a quasi-Buddhist spiritual retreat for clinical psychology students came back with ‘an enlightened, elevated look in his eyes’ and became really tiresome.

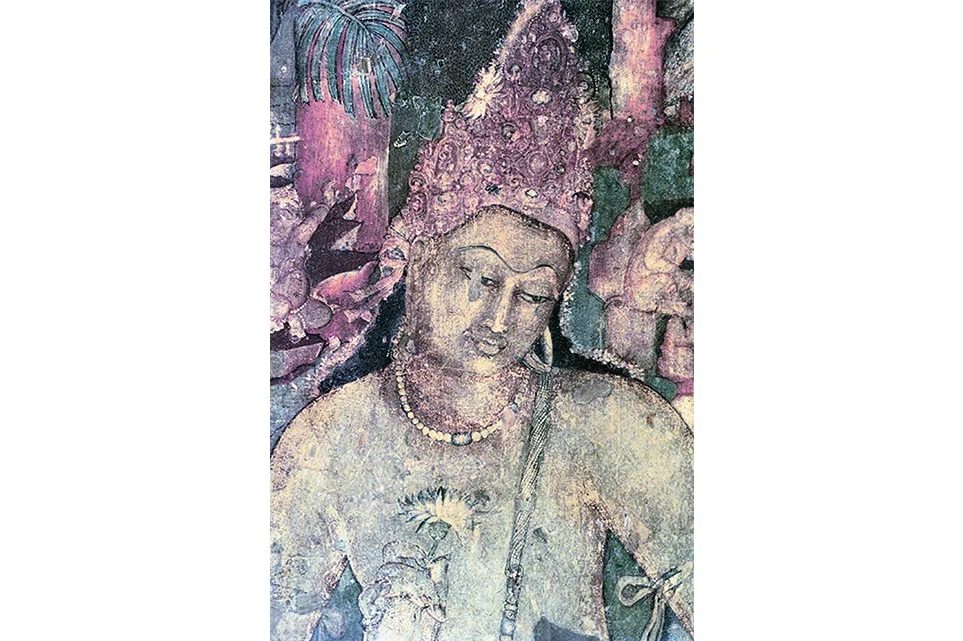

In particular, she wanted to test whether the ideals of a Tibetan Buddhist meditation master, Chogyam Trungpa, who taught renunciation of self, actually worked out in practice. She doesn’t say categorically that mindfulness and other spiritual therapies are proven to make you narcissistic, but she does observe a striking association between them.

As the study, published in the European Journal of Social Psychology, observes: ‘Spiritual training is assumed to reduce self enhancement, but may have the paradoxical effect of boosting superiority feelings… It can, thus, operate like other self enhancement tools and contribute to a contingent self worth that depends on one’s spiritual accomplishments.’

The research measured what researchers defined as ‘a feeling of superiority over those who lack the spiritual wisdom they ascribe to themselves’. There were three questionnaires, the first involving 533 people, the second 2,223 people and the third 965 people. They asked people to respond on a scale of 1 to 7 to a series of statements testing their ‘spiritual superiority’, including ‘Because of my education and experience, I am observant and see things that others overlook’, ‘The world would be a better place if others too had the insights that I have now’ and ‘I am more in touch with my senses than most others.’

And — are you actually surprised? — those who had taken part in forms of meditation scored higher in the questionnaires than those who had no spiritual training. The participants who engaged in practices like chakra cleansing and reiki scored around 67 percent more than people with no training, while those who had undergone mindfulness sessions scored about 50 percent higher than those who didn’t engage in practices such as meditation.

It’s the finding about mindfulness that’s striking. Relatively few people cleanse their spiritual auras or regress into former lives. But mindfulness is perhaps the defining practice of this millennium. It’s everywhere, from schools to boardrooms. It involves focusing on the moment in a non-judgmental sort of way, with especial attention to your breathing. It’s meditation for busy people. And in the pandemic it’s really taken off.

Sensor Tower, the app store analysts, report that between January and April, as the pandemic took hold, downloads of the world’s 10 largest English-language mental wellness apps rose from eight million to nearly 10 million downloads a month. Headspace, a popular mindfulness app, had 1.5 million alone. To cope with frightening and unpredictable events, people have tried to focus on the present moment, which is about the only thing they can control.

Of course, if you embrace a practice or belief you will think the world would be better if more people shared it. Lots of conventionally religious people meditate. But these mindfulness findings register something different: a sense of superiority over normal people. They suggest that the practitioners see themselves on a plane rather different from the spiritually unwashed.

Granted, there’s no shortage of smugness among ordinary religious people, but it’s the exact reverse of the virtue that’s most valued in Christianity, humility; it’s the paradox of the faith that he who humbles himself will be exalted. Judaism is about walking humbly before God. Religious meditation is directed outwards, at God, and expressed in our dealings with other people, especially those that society doesn’t very much value. Mindfulness, by contrast, is very much focused on your interesting self.

In our part of the world, mindfulness is almost entirely marketed as a non-religious thing. Jon Kabat-Zinn, an American popularizer of mindfulness, was introduced to Buddhism as a student at MIT. In 1979, he founded the program that became Mindfulness-Based Stress Reduction (MBSR) by adapting Buddhist teachings and removing the Buddhist framework.

American mindfulness is now a largely secular exercise — it’s spirituality for those who don’t do religion — and has moved even further, from spiritual practice to medical treatment. In 2007, the US National Library of Medicine says, only 70 scientific articles were published on its therapeutic uses. In 2019, more than 7,000 studies included the word ‘mindfulness’.

Divorcing mindfulness from its Buddhist roots is, I think, one reason why it has produced the spiritual swank registered in this Dutch research. As practiced here, it involves self-discovery and ego-bolstering, whereas its spiritual roots are underpinned by exactly the opposite aim: surrender and renouncing the ego.

When I was participating in mindfulness sessions, we were encouraged to practice compassion and to direct benevolent thoughts to a random stranger. There’s nothing wrong with this pleasant philanthropy; quite the contrary. But it’s easy to puff yourself up by projecting compassion on strangers without having to do any of the hard stuff that actual charity involves: engaging with the individual, in all his or her messy humanity. Heavens, you might actually have to think about their conditions of life.

Mindfulness has helped millions of people find calm. It has enabled them to direct their attention usefully on the here and now, though my mother did that whenever she told me to mind what I was at. But it’s not surprising that it can lead to narcissism, to undue focus on the self. It’s individualism in 10-minute sessions. At its worst it can, as Ronald Purser’s polemic, McMindfulness, suggests, result in a kind of quietism that absolves us from engaging in the world outside our breaths: ‘The ideological message [of mindfulness] is that if you cannot alter the circumstances causing distress, you can change your reactions to your circumstances.’

As for the Dutch study, we’re left to ponder whether mindfulness makes you more narcissistic or whether narcissists engage in mindfulness. It could, of course, be both.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2021 US edition.