Let me give you a free piece of relationship advice: just break up. If it’s more work than pleasure, if your heart sinks when they call, if you catch yourself writing ‘have sex’ on your to-do list, break up. Life is short, death is certain, relationships are for loving in, and if you can’t be with the one you love, you can at least leave the one you’re with.

I give this advice because I know that people in bad relationships don’t take it. They are like those evacuation refuseniks, stumping around on the volcanic hillside, saying they’ve lived there 20 years and they’ll be damned if the whole thing blowing sky-high will change that. You may be weary, you may be sad and sorry and enmeshed in tangled webs of silence and rejection, but you’re in it for the long haul. OK. Sit down. I have a podcast for you.

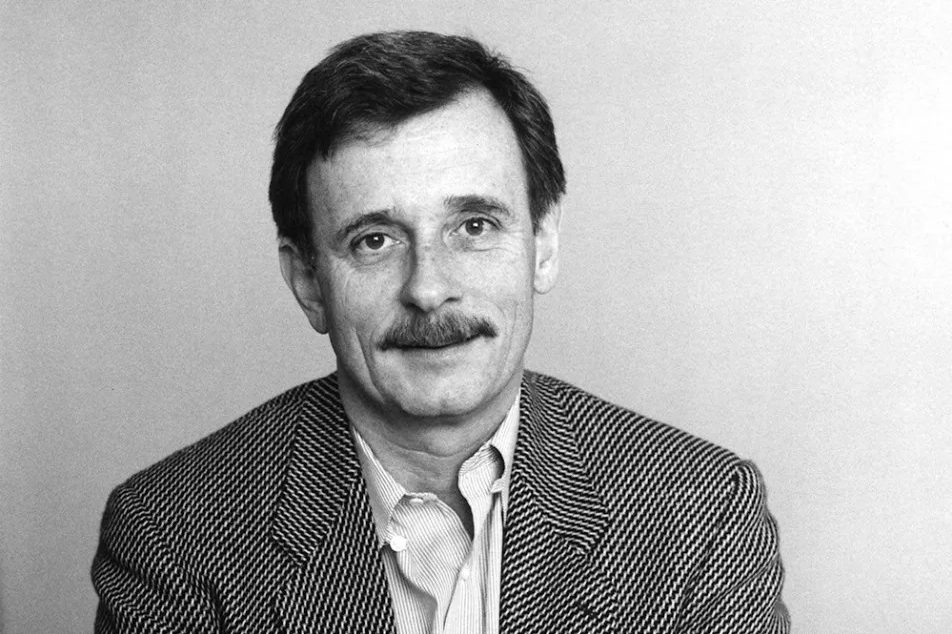

Where Should We Begin? is about people desperate to make it work. It is a thing of savage beauty. Each episode consists of a single counseling session, in which the host, relationship therapist Esther Perel, peels back layers of self-deception until she finds the writhing, needy ganglion at the root of the pain.

The episode titles reproduce the guests’ idea of their Big Problem. ‘It’s Very Hard to Live with a Saint’, goes one, in which she can do no right and he can do no wrong. ‘What Would It Take For You to Come Out?’, reads another, in which she is out and proud, but she isn’t, after four years together. Some of them seem self-explanatory. ‘He Loves Her, His Family Rejects Her’. ‘When I’m Manic I Cheat’. ‘The Chronic Philanderer’.

What we discover, over the course of a 40-minute conversation, is that these narratives are only approximations of reality. In Where Should We Begin?, the stories we tell ourselves are a functional fit: crude mittens, in other words, which we’ve fashioned to warm our raw and shivering hands. There may be wrongdoing and blame and inequality between these people, but that’s not what Perel is interested in. Tallying up black and white marks is what people do after they split. For those who refuse, the language of justice never quite holds, however much their friends think it ought to. I often think of something the philosopher Gillian Rose said. ‘There is no democracy in any love relation: only mercy.’

Perel herself is a merciless genius, not cruel, but all too aware that we perpetuate large-scale sadness by sparing the feelings of a moment. I spent a long time trying to work out where her accent was from: France? The French Pyrenees? The Basque Country? Alsace-Lorraine? She finds sibilants in words you didn’t know had any as she takes a necessary scalpel to some bunion of resentment. ‘Do you tell her, “You’re a wonderful lover”?’, she asks one half of a lesbian couple suddenly, pronouncing the word ‘lover’ with two ‘s’ sounds. ‘No!’ replies the woman, laughing. ‘Well, you should,’ cuts in Perel, without a hint of emotion and backed by the unanswerable rightness of a minor god.

Looking it up, I discover she speaks nine languages and grew up in Belgium.

In ‘Trapped in Their Own Story’, a man and a woman are struggling with intimacy of all kinds. She feels disconnected. That he doesn’t want to talk to her, that they don’t communicate. He feels he’s trying and trying to be what she wants, but it never measures up. And then there’s the infidelity. On both sides. And his porn addiction, which she feels is a betrayal and he feels is just a dude thing. Perel unpicks it with emotional intelligence to turn a dude’s hair white: ‘The betrayal — was it that he was watching? Watching more than you cared for? Watching other women and rejecting you? Making you feel that there was something wrong with you for judging it? Or being uncomfortable with it? Where was the betrayal for you?’ And on we go, into his background, her fears, their mutual anxieties. In less than an hour we see 20 years of unhappiness sifted down to a few abrasive gems — a process that’s a little like reading a brilliantly executed short story.

There are two ways to listen to Where Should We Begin?. The first is on your own, as a bracing journey into your past failures, long-forgotten conversations returning to your ear with the clarity of a 3 a.m. mosquito. The second way — and this is more my speed — is with friends, where the back and forth between partners becomes a kind of team sport, with people cheering and groaning each fresh revelation, or tearing their hair out and shouting: ‘Please! For the love of God, you two, just break up!’

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.