As the cross-Channel ferry noses into Ouistreham, I have a perfect view westward along the D-Day beaches. The excitement of arrival is heightened by the fact that this is the first time I have traveled to the Continent since COVID struck. Not since the age of 17 have I been absent from what the English call ‘Europe’ for so long — although of course, living in England, I have been in Europe all the time. My first objective on this trip is to see the new British Normandy Memorial at Ver-sur-Mer, the very place where my father landed with the first wave of the 6th Green Howards shortly after H-hour, 7:25 a.m., on D-Day in 1944. Located atop a high coastal bluff, the memorial commands a spectacular view of the Normandy beaches. Flanking a central monument is a giant rectangle of pale limestone columns, like a cloister but open to the skies, the columns connected by timber beams on top, as in a pergola. On these columns are engraved the names of 22,442 people from more than 30 countries who gave their lives while serving under British command in the Normandy campaign, from June 6, 1944 until the liberation of Paris at the end of August. I am deeply moved to find the names of two of my father’s comrades who were killed doing the same perilous job as he did, being forward observation officers for the artillery. The Normandy memorial is a thing of beauty. It reminds us Brits of deeper ties that no little contemporary spat over Australian submarines or Channel Island fish can break. You can contribute to its upkeep via britishnormandymemorial.org.

From Normandy, I drive to Brussels. The only thing that tells me I have crossed the frontier into Belgium is my GPS, which flashes up new speed limits. In Brussels, life is getting back to normal, although still with an awkward COVID dance at building entrances: putting on your face mask with one hand, searching your smartphone to find your proof of vaccination with the other, while hanging on to your papers with elbows or teeth. Politically, everyone is waiting for Godot — that is, the German elections.

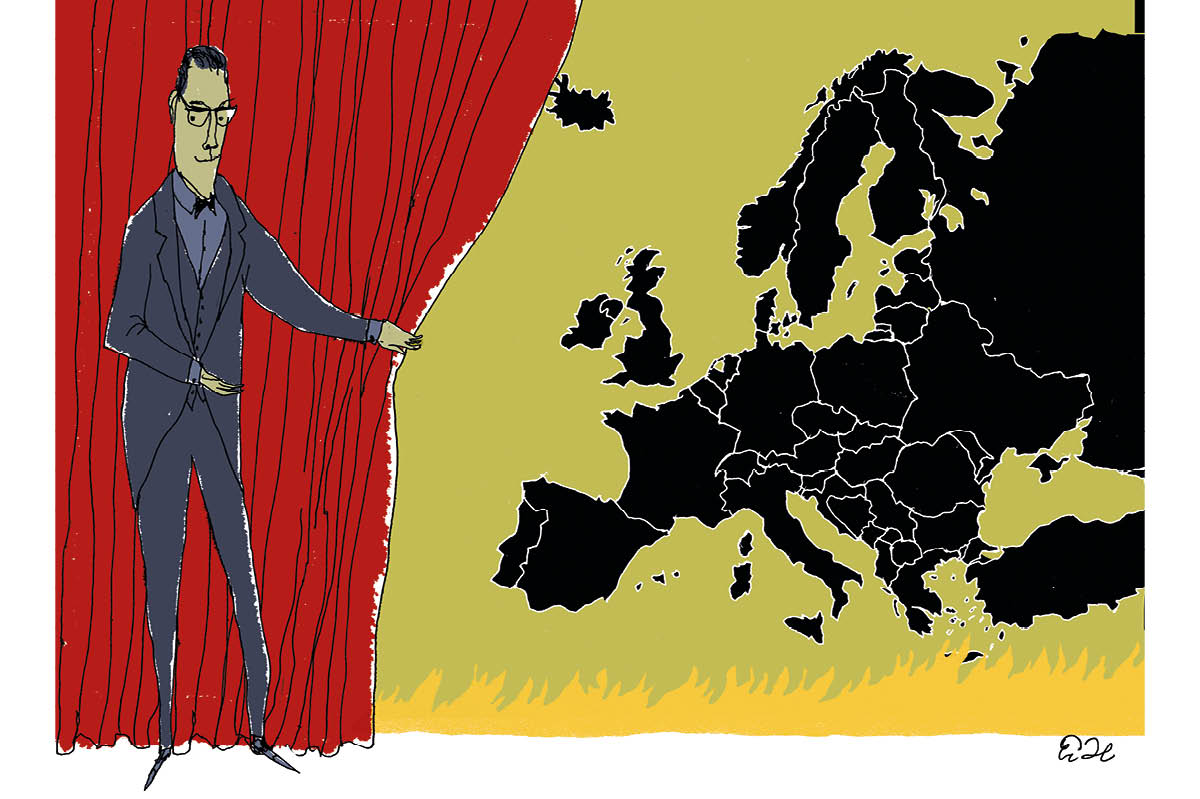

I fly on from the capital of Europe to, well, the capital of Europe. Actually, the European Union has many capitals and therefore none, but the most important national one is obviously Berlin. When I first came here, in the mid 1970s, the historic center was still visibly war-damaged, gray, gloomy and cut off from the West by the Berlin Wall. I wandered around the heart of the divided city with a 1923 Baedeker, its finely printed pink-and-gray map showing all the great buildings that were no longer there — the French embassy, the British embassy, the Hotel Adlon. People thought I was mad. Today, that 1923 map is a better guide to the city center than my 1970s East German atlas. I can have a coffee in the reconstructed Adlon, then pop round the corner to visit a new British embassy in its old place. And Germany is again Europe’s central power.

Berlin conversations about the coalition government that will emerge from this Sunday’s election are conducted in a curious code, composed of nicknames for possible coalitions based on the colors of participating parties: Jamaica (black, yellow, green), Deutschland (black, red, yellow), Kenya (black, red, green), Traffic Light (you guessed). In an unpredictable race, and with Germany’s complicated electoral system, any of these coalitions might be arithmetically possible. The two things we know for sure are that it will be a coalition and will be formed only after many weeks of fraught negotiations.

Meanwhile, Angela Merkel will continue as chancellor. I’m told the chancellery is already making contingency plans for her to attend a European Council in Brussels in mid-December. What government finally emerges matters a lot, partly because of things she could not have anticipated, such as COVID, but also because in many areas she has muddled through rather than acting strategically: the eurozone, Russia, China, to name but three. I’m struck by how critical many of my German friends are of the balance sheet of her chancellorship. Her great achievement is to have kept the European show on the road through a decade of crises, but she leaves her successors a mighty to-do list.

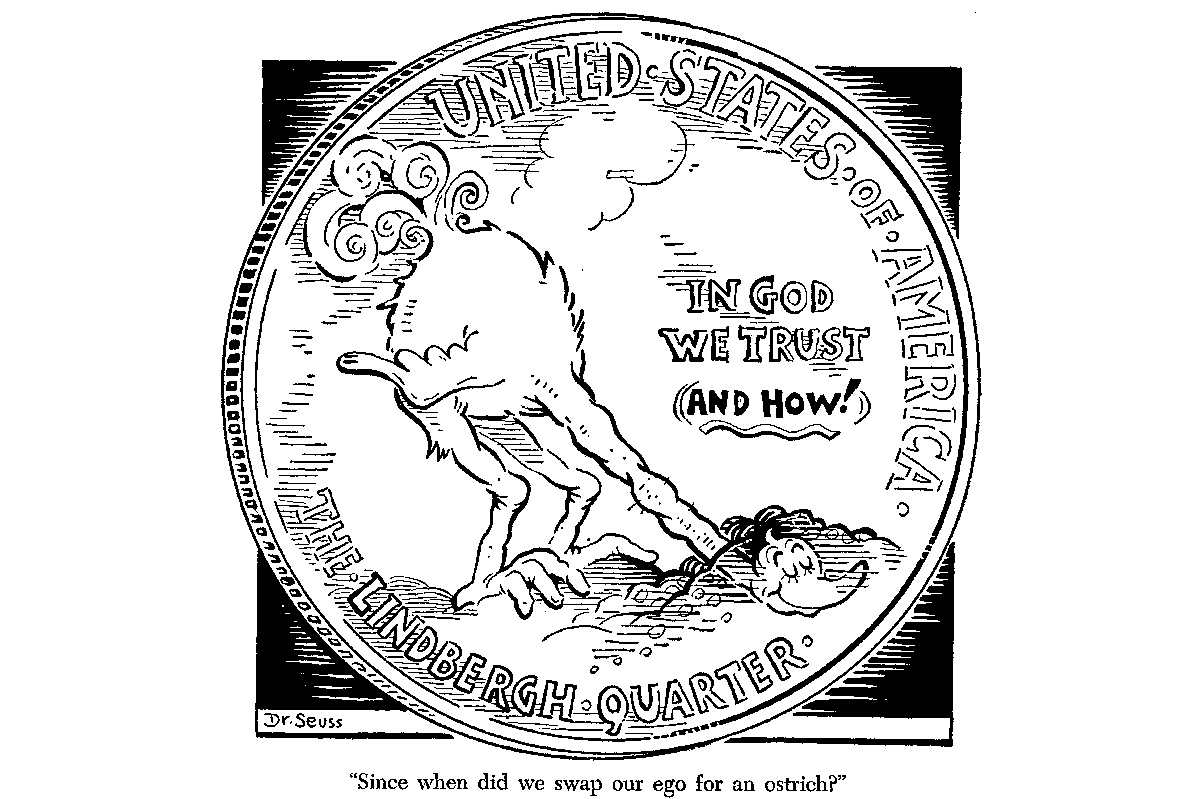

One of the strangest things about this election has been the almost total absence of foreign policy. In three long television debates between the candidates for chancellor, the rest of the world was hardly discussed at all. This despite the fact that German forces were directly impacted by the precipitous American withdrawal from Kabul. Everyone pays lip service to building up Europe’s ‘strategic autonomy’, but it’s not a focus of serious political debate.

Short-haul air travel has long since lost any glamour it might have had. The combination of COVID, the ongoing terrorist threat and a heavy rainstorm turns my flight back to England into a sweaty obstacle race of security, passport and medical document checks and a long delay before piling into a cramped, pressurized metal tube, relieved only by British Airways’ munificent provision of a small bottle of water and a packet of crisps. I find myself agreeing with the old lady, quoted by the musical duo Flanders and Swann, who said that if the good Lord had intended us to fly, he would never have given us the railways.

Timothy Garton Ash is professor of European Studies at Oxford University. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.