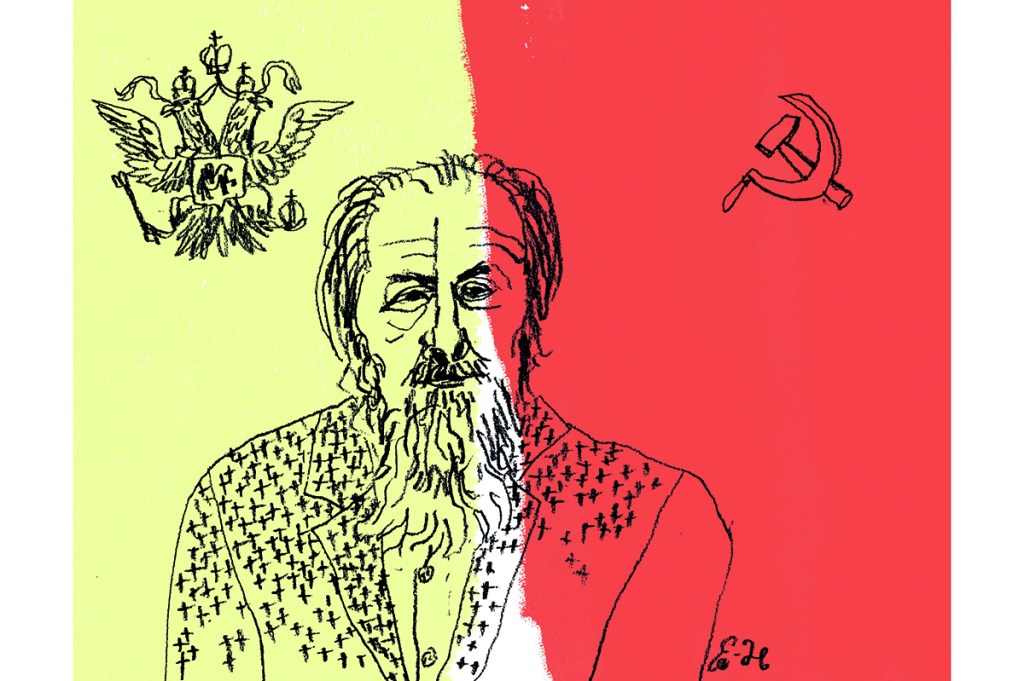

In the mid-1970s, exiled from the Soviet Union for exposing its vast crimes against humanity, and having won the Nobel Prize in Literature for that endeavor, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn turned his back on the lionization that awaited him in New York and other cultural capitals of the West and instead settled with his family in the woods of Vermont. Avoiding visitors for the better part of the next two decades, he churned out half a dozen or so books, averaging roughly 750 pages each, that together tell the story of the Russian Revolution and its antecedents. This act of sheer energy, self-discipline and renunciation of the conventional worldly pleasures bestowed by the literary elite was in the spirit of Russia’s own eastern monasticism. It made Solzhenitsyn, a conservative traditionalist who died in 2008, not merely a great man of literature, but one of the great men of the twentieth century.

The Red Wheel series consists of discrete “nodes,” as Solzhenitsyn calls them: August 1914, November 1916 and, so far, three fat volumes of March 1917. (More are to come as Marian Schwartz’s work on the translation continues.) Most of The Red Wheel, except for August 1914, was substantially written in Solzhenitsyn’s self-imposed exile in Cavendish, Vermont, before his return to Russia following the collapse of the Soviet Union.

These novels are history told in the spirit of the present tense. Solzhenitsyn seems to leave nothing out, not even the tedium of a deranged marathon of sleepless nights in the palaces of Petrograd and elsewhere, fueled by tea and alcohol. He relives and recreates how it all happened in Russia in the second decade of the twentieth century, and he does not allow this pivot of world events to be bastardized by the clever hindsight of historians and the comfortable value judgments of our time. It speaks volumes about the decline of our culture that only the first two nodes — August 1914 and November 1916 — were brought out by a Manhattan trade publisher. Thanks to the University of Notre Dame Press, we have and will have the rest.

Solzhenitsyn painstakingly and minutely demonstrates — rather than simply states — how order is more important than freedom, since without order there can be no freedom for anybody. Order in pre-revolutionary Russia constituted a medieval totality, represented by the absolutism of the Romanov dynasty. Czar Nicholas II, as Solzhenitsyn both shows and intimates, was stupid, indecisive and self-destructive. He had no judgment. But as much as Nicholas retreated into a reactionary past — even as Russian society was experiencing the early upheavals of modernization — there could simply be no Russia without the monarchy. Alas, Nicholas was hated as much as his family was necessary; this is the signal tragedy that Solzhenitsyn captures in these novels.

In terms of ruling institutions, early twentieth-century Russia was less developed than late-eighteenth-century France:

“The French Revolution had gripped the minds of society on a mythical plane. Nonetheless, the French monarchy resisted for three years, while ours — all of three days [in March 1917]. How on earth could everything have fallen apart so quickly?”

The answer comes not through grand concepts or thrilling explanations, but through the monotonous course of hundreds of details, complete with newspaper clippings from the time, as Solzhenitsyn relates the events that occur in the minutes, hours and days that follow the czar’s decision to abdicate. A plethora of gatherings continue literally all day and night among politicians and officials, but few of the meetings have any structure. Purposelessness predominates, everyone is interrupting everyone else and next to nothing gets accomplished. The daily functions of authority, so ordinary that we in the West still take them for granted, turn out to have no existence in Russia without the Romanov dynasty: “What agenda! No matter what agenda was announced, it was never going to be followed.” Meanwhile, criminals are released from prisons. Soldiers desert from the army after nearly beating to death their officers. Mutinies lead to the collapse of the Baltic Fleet. It is as if the entire Russian military organization is being eaten away by “microbes.” The army, the “most stable of society’s organizations” is “melting and spilling away.” Gangs of arsonists set fire to public buildings. Entire staffs disappear from government offices, along with the cumulative safety that such flimsy institutions had attempted to provide to society. Youths even tear down a statue of the great modernizing prime minister, Pyotr Stolypin, who had struggled to reform the monarchy before his tragic assassination in 1911.

And yet at the same time there was jubilation in every city across the longitudes of Russia. All of Petrograd was celebrating for days. Bands formed and played in the streets of towns. People embraced. Portraits of the czar were taken down and royal monograms ripped off and unpicked from clothes. All this was actually thought to be a moment of national greatness. Almost everyone implicitly assumed that the revolution would end naturally with Nicholas’s abdication, and in fact was all about Nicholas’s abdication. That was not only tragically wrong, but completely opposed to the emerging facts on the ground and the eternal laws of politics. What Solzhenitsyn gives us in The Red Wheel, and particularly in this latest volume, is the organic process and tactility of a political transition which began with Nicholas II’s abdication but had its immediate roots in the outbreak of World War I in August 1914.

The delusional naïveté of the early revolutionary process is encapsulated in Solzhenitsyn’s portrait of the young Aleksandr Kerensky, the key government minister in the months between the revolution of February 1917 and the October Revolution, the coup that brought the Bolsheviks to power. Kerensky darts about with a “swift, springy step” as he endlessly holds forth about a “free Russia” and a “bloodless revolution.” He rarely stops speechifying as he rides the intoxicating revolutionary crest, and he is always greeted by thunderous hurrahs. Kerensky fled Russia in 1918 and spent the last five decades of his life in exile. He was among the lucky ones. Many of the other characters in Solzhenitsyn’s vast history ended up imprisoned and executed, as the perilous and intoxicating course of “bloodless revolution” led to the murder and death of tens of millions.

The “swinging of history’s weight,” as Solzhenitsyn puts it, can be determined by the barest of contingencies. Had Nicholas not abdicated for both himself and for his son; had Grand Duke Mikhail Aleksandrovich not been forced to abdicate almost immediately after the crown passed from Nicholas to him; had the somewhat more capable Grand Duke Nicholas Nikolaevich been able to secure the throne following his military command in the Caucasus; had Stolypin not been assassinated; had Kerensky had better political instincts and been more than a gifted and inspiring speechmaker; had the Czarevich Alexei’s hemophilia not distorted the life and politics of the royal family — much might have been different. The Bolsheviks might not have gained control in the way that they did and when they did. Much hung on a thread, and because the Russian Revolution itself hung on a thread, so did the trajectory of the twentieth century.

An individual life consists of mistakes, according to Solzhenitsyn, and so does history. That is only one of the tough lessons he teaches in this most recent volume. The strong, he says, know how to lead and also how to obey, whereas the weak “require the illusion of independence.” Order, no matter how complex the social organism, rests upon some kind of chain of command or multiple chains of command. Hierarchy is everything, especially in Russia, which was a huge and geographically endless organism lacking a real middle class. Given this and the way in which events unfolded, the only question was what kind of dictatorship Russia would have.

But did it have to happen as it happened? Solzhenitsyn does not say it, but if the royal family had not been executed — and if a quasi-constitutional monarchy had been established — the twentieth century would have been far less bloody. Instead, the abdication and subsequent arrest of Nicholas II and his family led to a vacuum of authority. The worse the anarchy, the worse the solution. Meanwhile, Lenin, brooding in his Zurich exile, had his mind fixed on the mistakes of the Paris Commune (the insurrection that followed France’s defeat by Prussia in the war of 1870-71). As Solzhenitsyn inhabits the thoughts of Lenin, the leader of the October Revolution-yet-to-come condemns all displays of weakness and humanity. We must seize the banks. We must not be magnanimous. Don’t save people in order to re-educate them; conduct cellar executions instead: “The proletariat had to be taught pitiless mass methods!”

And so it happened thus. As each new book in the series appears in translation, Solzhenitsyn’s Red Wheel is emerging as the ultimate monument to the perils of illusion and disorder.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.