A dinner party without good conversation is like flat Champagne: pretty pointless. It’s like that not-so-funny joke about the inscription on an atheist’s tombstone: “All dressed up and nowhere to go.” Of course at a miserable dinner party you and your glad-rags have reached a destination of sorts, but (as for the late atheists) it’s not the one you were expecting.

How to avoid such an infernal disappointment? Jean-Paul Sartre famously felt that hell was other people; all I can say is, that’s no attitude to bring to the table. To ensure that scintillating repartee is the order of the evening, let Sartrean egotism be set aside in favor of the timeless advice of another Jean, bearing the surname of de La Bruyère: “The spirit of conversation consists much less in being witty oneself than in bringing out the wit of others.”

Of course, it helps if the stage is set with a carefully prepared — even if simple — meal and pleasant lighting (a candle never hurts) and if the social wheels are given a little oiling in the shape of alcoholic beverages. And this is where the fizz comes in.

Try a Blushing Angel, which starts with two ounces of Dubonnet and four of Champagne (or prosecco). An ounce of cranberry juice turns the angel a delicate pink, and a lemon twist would complete its embarrassment, were it not for the fact that angels are pure spirits and do not experience emotion (even when crowned with lemon twists). I was served this drink recently, and while it may not have actually had any measurable effect on my levels of wittiness, I definitely felt wittier. La Bruyère could not have avoided tendering his rare approval to my delightful hosts. In the Christmas season, the lemon twist can be swapped for a floating cranberry and a pine-needly branch of sugared rosemary.

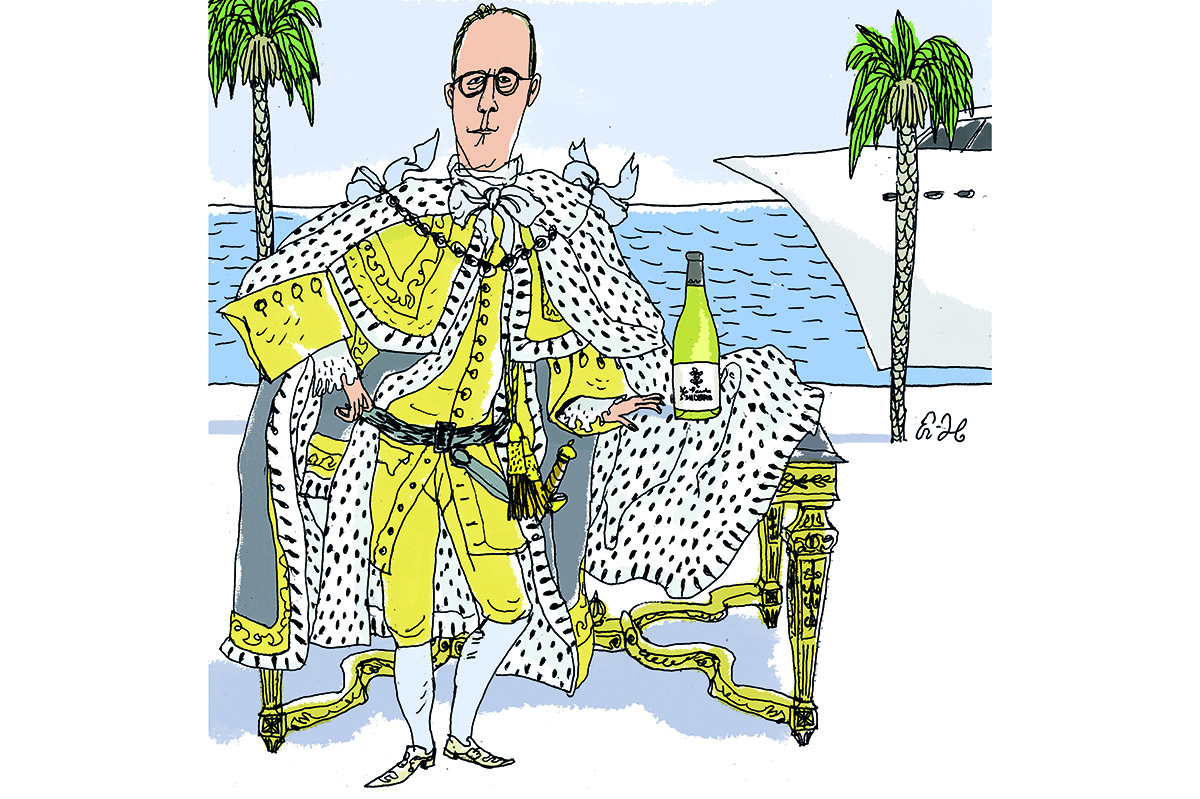

A Kir Royale is also a wonderful choice for Christmas: you pour half an inch of crème de cassis in the bottom of a flute and fill it up with bubbly, preferably a dry Champagne. The crème de cassis turns it a lovely red. Ubiquitous at formal French occasions, Kir is named after a rather colorful character, a Catholic priest, Canon Félix Kir, who served on a municipal committee running the city of Dijon when the mayor left during World War Two. Canon Kir got involved with the Resistance and helped thousands of prisoners escape, and, despite various contretemps, survived the war to be appointed — rather unusually for a priest — mayor himself, a position to which he was reelected over and over until he died in 1968.

It had been a custom for the mayors of Dijon to serve their guests a blanc-cassis since the early 1900s, a drink composed of white wine and Dijon’s specialty crème de cassis. Canon Kir, who was reportedly far from averse to building his own legend, decided to name the drink after himself. When he was elected to the National Assembly, he used to bring along the wherewithal to mix up a few for his traveling companions. He wore his black cassock everywhere, including at the National Assembly, and once when another legislator accused him of being a turncoat, he shot back, “Dear colleagues, I’m being called a turncoat, but look, my clothes are the same color on both sides!”

Replacing the white wine with Champagne makes a Kir into a Kir Royale, and at Christmas, once you’ve invited the Blushing Angel to announce peace on earth to guests of good will, it must be followed by a Kir Royale in honor of the newborn king.

In order to enjoy peace on earth among one’s dinner guests, however, it’s wise, over and above serving the right cocktails, to invite people likely to find themselves in sympathy with each other. That said, kindness and genuine interest in one’s guests are the real magic. Flowers open in the beneficent warmth of the sun; in cold and frosty air they stay tightly closed, if they don’t curl up and die of blighted feelings.

My friend Alex threw the best dinner parties you could ever hope to attend. I am sorry for everyone reading this who hasn’t been to one. Course after course of exquisite food, prepared by him and his wife — both brilliant cooks — would appear; glass after glass of wine would be poured. But best of all was the conversation. A world-class jeweler, Alex had an eye for beauty both in raw gemstones and in personalities and a gift for bringing out the best in his friends. The evening would pass in a swirl of laughter, stories, verbal swordplay, delightful aromas and joie de vivre, but most of all in a sense of shared love for everything good, for friendship and wit and wine, for all the individual manifestations of what Yeats called “beautiful lofty things.” It was the love of a cataloguer and collector of goodness, a love that emanated from our host, and touching his guests like lamplight, turned us temporarily into gold.

I remember hearing a theatrical choreographer hold forth on Renaissance dance. The dancers, she explained, were supposed to move in elaborate and gorgeous patterns that would look beautiful from above, like swirls in a jardin à la française, so God could look down with pleasure on their imitation of the celestial dance, their participation in the harmonious motion of the spheres.

At its best, conversation is an imitation of the celestial dance: some stepping out, others falling back; a twirl, a pirouette, a jest; each one knowing when to hold back and when to advance, reading the cues, following the music, adjusting to suit one’s partner — not with frowns of concentration as if faced by a challenging math problem, but with the delight of a top athlete in the zone. Not only do you know that rules and technique make the game better, you’ve integrated them so fully you can forget them and just play — as creatively and strategically as you like. Is there a better definition of freedom?

Follow these simple rules, and your parties will never fall flat. Instead, you’ll echo Dom Pérignon on Champagne: “Come quickly, I am tasting the stars!”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.