Six, a British musical about the wives of Henry VIII, is a scrupulously specious masterclass in frivolity. These onetime queens, blinged and bedazzled as fabulous pop-diva Kweens, undertake a six-way singing competition to decide who had “the biggest, the firmest, the fullest… load of B.S. to deal with” from their kingly husband. Backed by a live band, the sextet’s set amounts to the love child of RuPaul’s Drag Race and the Super Bowl halftime show.

Those hoping for revisionist revenge fantasy will leave disappointed. Those seeking dramatic tension, character development, tragedy — anything having to do with the second half of the phrase “musical theater” — won’t find it here. Rather than locate these elements in the source material (where they are abundant), Lucy Moss and Toby Marlow, who wrote the script in 2017 while studying at Cambridge, pretend to a historical aura while gleefully emptying their subjects of historical content. As Moss explained in an interview, it’s “about showing that women and non-binary people can tell stories that don’t include men.” Sorry, Bluebeard, it’s ladies’ night.

The six historical women are grafted onto six contemporary pop-music brands. Catherine Howard (Samantha Pauly) delivers her bubblegum anthem “All You Wanna Do” à la Ariana Grande, and Anne Boleyn (Andrea Macasaet) evokes pop-punker Avril Lavigne with “Don’t Lose Ur Head.” These mashups constitute the show’s creative achievement: they are clever — devilishly clever — and the performers all acquit themselves admirably in their delivery. Brittney Mack commands attention as a Nicki Minaj-ian Anne of Cleves. Adrianna Hicks as a Beyoncé-inspired Catherine of Aragon is, quite simply, electric.

Ay, but there’s the rub. Productions like Hamilton have shown how the pop-remix gambit can profitably enliven history, especially for youngsters. But when Jane Seymour (Abby Mueller), who died after just seventeen months as queen, boasts herself “unbreakable” in the number “Heart of Stone,” one may fairly wonder whether the show’s historical interest is genuine.

Early on, these scary wives of Windsor claim that “history’s about to get overthrown.” This is a clever trick: remove the history, and the overthrow’s a breeze. Six makes a show of glancing at history and sprinting in the opposite direction. What’s left is catnip to our perpetually adolescent consumer class.

Given the starchy demographics of the typical Broadway audience, a big challenge facing any play about black life is to avoid minstrelsy — i.e., serving up warmed-over stereotypes about blacks to satisfy white expectations. These stereotypes are no longer so unsubtle and pernicious as the ones that produced Sambo, but our society’s appetite for black culture has grown immensely since the nineteenth century. So the opportunities for racial grift have expanded, too.

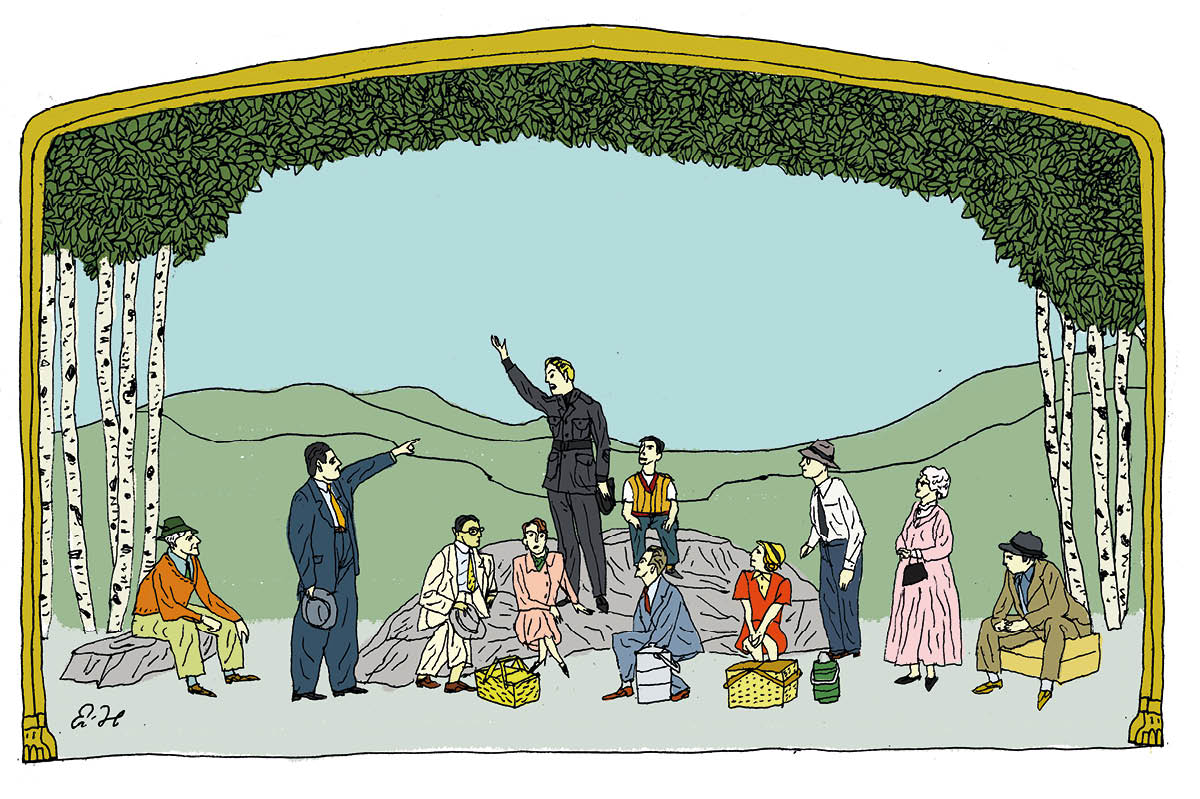

In light of this, Chicken & Biscuits left me feeling a bit uneasy. The play, a new comedy about the funeral of a black family’s patriarch, wasn’t all bad. Amateurish and clunky, yes, but it has heartfelt moments. The script is Douglas Lyons’s first full-length play; the director, Zhailon Levingston, is making his Broadway debut. The action follows a plot that daytime-TV audiences might recognize, if not from the soaps, then from the British dark comedy Death at a Funeral (2007) or the 2010 remake with black Hollywood stars. Family members gather from afar for a funeral; they bicker; a secret comes out; all are shocked into loving and accepting one another. These aren’t black stereotypes, just worn-out theatrical ones.

Nor was it the title that gave me pause, though I can’t imagine Refried Beans & Rice will be hitting stages anytime soon. No, what made me uneasy about Chicken & Biscuits was the way it portrays traditional Christian life as practiced by millions across the country today. Will Arbery’s Heroes of the Fourth Turning did something like this off-Broadway a couple years back, except with white conservative Catholics instead of blacks, and liberal audiences marveled at the suggestion that those deplorables could have such rich inner lives. And yet here, black spirituality is so taken for granted that it’s bound to be a source of comedy, not drama, when the minister gets animated in his eulogy or when “Mother Jones” strains to hit the high notes.

Does that make Chicken & Biscuits a brand of minstrelsy? I don’t think so, but I can’t shake the notion that black Christianity generally serves as a proxy belief for religiously progressive whites, who indulge or reject it by convenience. It’s all smiles in the theater, but when it comes to, say, closing black churches during a pandemic, the swing is fast enough to give you whiplash.

Six is at the Brooks Atkinson Theater, New York City (open booking). Chicken & Biscuits is at the Circle in the Square Theater, New York City through January 2. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2021 World edition.