In March 1963, the Fantastic Four had a fractious encounter with Spider-Man and a dust-up with the Hulk — a busy month which effectively launched the Marvel Universe as an ecosystem of characters whose individual stories all contributed to one giant narrative.

There is nothing quite like it: an endless, collaborative roman-fleuve of wildly variable quality, constructed over several decades by hundreds of writers, artists and editors, driven by a combination of personnel changes, marketing schemes and hasty improvisations. As a fourteen-year-old Marvel nut, I had a decent handle on it; but now, if I nostalgically check out a character’s Wikipedia page, I’m swamped by an unfathomable splurge of deaths, resurrections, shifting alliances and parallel universes. Who can keep up with this stuff? Who would want to?

Perhaps only Douglas Wolk. The critic committed himself to reading every single Marvel Universe comic book published between 1961 and 2017: around 27,000 issues, running to more than half a million pages. That’s quite a task. An even bigger one is to condense the experience into a book that isn’t as bewildering and exhausting as its subject matter. Fortunately, Wolk is a capable guide, wry, friendly and astute, who assures us: “What the story wants from you is not your knowledge but your curiosity.” Now that Marvel’s film franchise, the MCU, is the world’s biggest, the story resonates far beyond the pages of comic books.

All of the Marvels is, necessarily, an unusual book. After fifty pages of amiable methodological throat-clearing, Wolk devotes chapters to crucial themes or characters, broken down into landmark issues and festooned with footnotes. It isn’t chronological, but along the way we learn how the middle-aged huckster genius Stan Lee (“a con man who delivers the goods”) and artists such as Jack Kirby and Steve Ditko reinserted the superhero into the heart of American mythology in the early 1960s. Much depended on grumpy outsiders and the hubris of very clever men.

Lee and his colleagues bequeathed a mountain of raw material to subsequent writers, many of whom outdid the originators; it took seventeen years for Daredevil to realize its potential, twenty-one for Thor and thirty-two for Black Panther. You might call it licensed fan fiction: people who grew up with these characters get to reimagine them with few hard-and-fast restrictions. Change is inevitable but not necessarily permanent. Unless you’re Spider-Man’s Uncle Ben, death is rarely the end.

Wolk succeeds on two levels. He’s an astute close reader who can elucidate not just the chemistry between writers and artists but also the underrated role of colorers and letterers; and he tracks the evolution of Marvel’s abiding themes (“the role of gods and the role of kings, where power really lives, what might be beyond the world we know”) with the right mix of respect and amusement.

It’s clear that current complaints that Marvel has become too woke are misguided. The 1970s gave us student protesters, sincere if shaky efforts towards racial diversity, and a Watergate-era Captain America so disgusted by his own government that he quit. Wolk points out that Marvel’s “sliding timeline,” in which the events of 1961’s Fantastic Four #1 are always fourteen years ago, means that the 1970s no longer happened, but still. He digs into the letters pages to unpack a long, respectful dialogue between the writer Doug Moench and the reader Bill Wu about racial stereotyping in Master of Kung Fu. These conversations are not new.

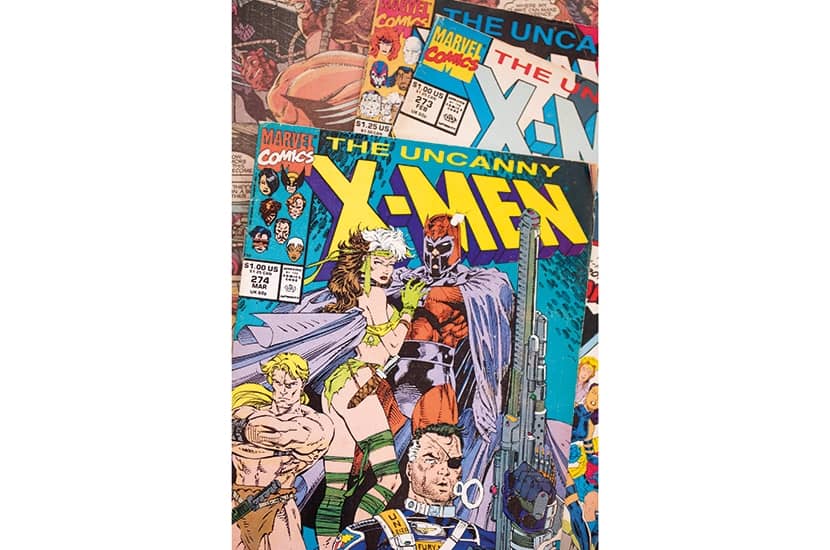

Most successfully, Chris Claremont’s sales-busting 1975-91 run on the X-Men established the mutants as a fluid metaphor for the Other. As Wolk writes: “X-Men became to comics approximately what David Bowie was to music — the signal to every misfit out there that they weren’t alone and that things might be okay after all.” Claremont’s pioneering dedication to female characters coexisted with a marked taste for mind-control plots and fetish gear. Such individual idiosyncrasies, from Frank Miller’s infatuation with ninjas and vigilantes to Bill Sienkiewicz’s jagged impressionism, have made the comics far bolder and stranger than the movies they have inspired.

I would have liked more analysis of classic, self-contained narratives and fewer recaps of knotty, multi-character cross-over events. But then Wolk’s fundamental subject is the mad puzzle of continuity: the form of storytelling more than the content of individual stories. Current writers, such as Al Ewing and Jonathan Hickman, operate with a Wolk-like blend of knowledge, affection and irreverence, in playful conversation with Marvel’s heritage. The worst writers simply find ways to keep characters busy, while the best propose new answers to foundational questions.

Twenty years ago, this book would have been a niche proposition. Now, largely thanks to the MCU, universe-building is increasingly essential to movies and television, with billions of dollars riding on narrative plate-spinning and the rejuvenation of old IP. Marvel has been doing it for sixty years, if not always well, and this generous, freewheeling book explains how.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.