In a perfect world, lawmakers responsible for crafting defense policy would actually debate defense policy. Yet rarely does this occur when the annual National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) works its way through Congress.

If there is debate, it typically revolves around numbers: how much money does the Pentagon need to keep the United States safe and ahead of its strategic competitors? How many F-35 airframes should be purchased for the Air Force? How much cash should be appropriated for the various “assurance initiatives” the Defense Department runs on a daily basis?

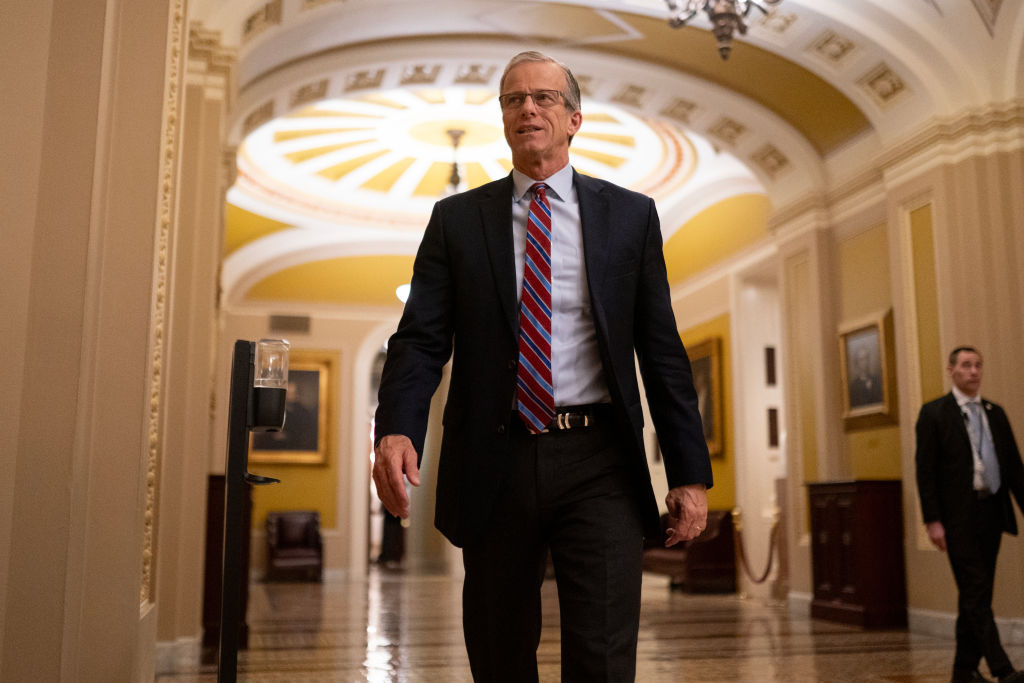

This year was no different. The Senate this week sent a compromise $768 billion NDAA to President Biden’s desk in a resounding vote after a multi-day hiccup over amendments killed the original version. Members of Congress, per usual, patted themselves on the back for a job well done. The package “addresses a broad range of pressing issues, from strategic competition with China and Russia, to disruptive technologies like hypersonics, AI, and quantum computing, to modernizing our ships, aircraft, and vehicles,” Senate Armed Services Committee Chairman Jack Reed said in a statement.

Defense hawks, who complained that the White House’s request was puny, are mollified. They successfully added $25 billion to President Biden’s draft budget, buying five more F-15EX jets and 12 more F/A-18 Super Hornets than the military asked for. The Pacific Deterrence Initiative was hiked to $7.1 billion, while $4 billion was authorized for the European Deterrence Initiative — $570 million more than the Pentagon wanted. Lawmakers also blocked the Air Force from retiring the A-10 Warthog, a close air support beast considered one of the most vital during US operations in Iraq and Afghanistan.

The underlying strategy driving these decisions was left unchallenged. Policymakers appear to be so interested in throwing more cash into the Pentagon money pit that they didn’t bother to assess whether the current defense strategy is serving the US well. Primacy, under which America aims to preserve its status as the dominant power in all regions of the world, continues to take on an almost cult-like aura. Yet in reality, it strains the joint force and encourages our soldiers, sailors, airmen, and marines to conduct missions of dubious security value.

Look no further than the routine peacetime forward presence patrols the US Navy participates in, a rate of activity so regularized that the fleet is wearing down and readiness is suffering. Readiness, as former deputy defense secretary Robert Work wrote for the US Naval Institute this month, it is a prerequisite for winning a war. But when the mission is simply to be present for the sake of being present, that readiness begins to atrophy.

The United States is a remarkably secure country, surrounded by friendly neighbors to its north and south and massive oceans to its east and west. It possesses the global intelligence networks, partners, and strike capabilities to hit an enemy hard at short notice with ruthless precision. Despite consistent worries about it losing its edge to rising powers or drifting down the road to decline, no country on the face of the earth seriously believes that America wouldn’t defend its core interests vigorously. And if a country was foolish enough to believe this, it would be in for a rude awakening.

China’s impressive military modernization, Russia’s brinkmanship near the border with Ukraine, and Iran’s nuclear program don’t make this fact any less salient. They simply force US officials to learn and adapt their approach to managing these challenges effectively and efficiently.

In many cases, that should mean Washington doing less and its allies doing more: Europe should step up collectively to establish a stabilizing modus vivendi with Moscow, while nations in the Indo-Pacific should embrace primary responsibility for their own external defense. In other cases, it necessitates that America place more trust in the non-military aspects of its power, with diplomats engaging in tough but flexible negotiations with an adversary to avert a potential crisis. Sometimes, it means avoiding a situation entirely, when US interests are minimal and the costs of involvement outweigh the benefits (you can put civil wars and ethnic conflicts into this category).

What it doesn’t mean, though, is maintaining a bloated American force posture overseas, discouraging allies from carrying their share of the load, and mistakenly thinking a lack of money is the reason why US defense policy has so many problems.

Strategy guides budgets. But if the strategy is defective, it doesn’t matter how high the budget is.