When I first moved to the country, I was intrigued by the sight of people walking sheep on a leash round and round the front garden of a neighboring farmer. City girl that I am, I wondered if they were receiving some kind of special therapy. Equine interaction is supposed to help with certain anxiety disorders, why not sheep-walking for, say, insomnia?

It turned out, however, that the sheep-walkers were members of the local 4-H club preparing to show their market lambs at the fair, an event I was later privileged to witness. But I was put to the blush when the judge, a tall, competent-looking man in a checked shirt and green boots, commented loudly on the fine chops displayed by the winning entrant. Is it just me, I thought, or is it a bit tactless to discuss chops within earshot of the woolly victim?

All par for the course in the mutton market, naturally. I’m very far from opposing the consumption of meat. But it’s humbling to think that the sturdy young lamb bracing trustingly against its owner, looking up with gentle, if not overly intelligent, eyes, will give its life to feed and strengthen me, or if not me, my brother, my friend, my fellow human.

In one way, what could be more obvious? But in another way, it’s breathtaking — that living things, even if they’re “only” plants or mollusks, must give their lives to sustain our lives. Face it: we can’t live on rocks or sand.

It doesn’t do to think too much about this kind of thing. Perhaps it’s all right if you’re a farmer, accustomed to caring for animals with an eye to dinner — though I’ve noticed few farmers care for rare meat, preferring to distance their dishes from the barnyard with a thorough cooking job. But considering that life must give itself for you to live is a bit like looking down over the edge of a cliff: heady, terrifying, and if you do it for too long, you get dizzy and fall.

Occasionally, though, these existential questions rise up to confront us, nailing abstractness firmly to the barn door with the warm substance of a woolly lamb flank or the juicy richness of its leg on a plate. It is what it means. The medium is the message. It’s the place where, as Jordan Peterson would have it, narrative and reality touch. The gentle lamb sacrifices itself to give us life, and we sit around the dinner table, forks and knives in hand, a bottle of claret or two, accepting its sacrifice with varying levels of joy and gratitude, depending on the caliber of the cooking. Little gratitude is drawn by boiled mutton. Much joy, on the other hand, can be sparked by the foodie Andy Baraghani’s braised lamb shanks with pomegranate and walnuts.

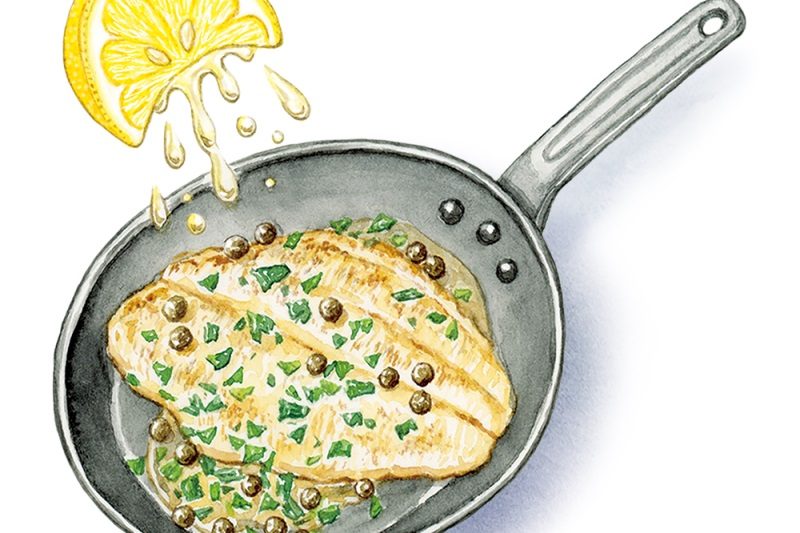

For Easter, why not plan a crown roast of lamb? Crown roast is the most triumphant meat cut I know. The spare rib sounds lean and penitential (belying its delicious nature). The shank sounds good, but humble, like a lay brother of sorts: one reduced to shanks’ mare does not ride in a Rolls-Royce. Saddle and shoulder both sound like work — even picnic shoulder sounds like it’d be no picnic to carve. Sirloin tip sounds impressive but static, like the Iberian peninsula or a peak in Darien. Filet mignon is upper-class and luxurious but lacks leadership skills. Steak sounds honest, honorable and reliable, more of a loyal henchman than a prince. It must be admitted that prime rib is a credible contender for the throne. But crown roast was born to reign.

It’s made with two or three frenched racks of lamb, curved into a circle so that the bones radiate outward, tied tightly in place with twine. (Frenched doesn’t mean that they’ve been given the side-eye by somebody from Paris: it means that the meat and sinew has been trimmed off the ends of the bones for beauty’s sake. True beauty is more than skin-deep.) Aluminum foil frills decorate the ends of the bones. In the middle goes a stuffing of ground lamb, sausage meat jeweled with dried fruits, rice pilaf or couscous, filling out the center of the crown. It’s easiest if you get the crown preassembled from the butcher. I’ve succeeded in assembling one before, but it took a lot of time, about two rolls of butcher’s twine and all that was left of my patience before the slippery racks consented to settle in an approximately circular shape around the metal bowl I used as a form. At that point, you don’t want to cook it anymore — you want to hurl it out the window.

If you’re doing a raw meat stuffing, the cooking is a bit precarious because the stuffing will cook at a different speed from the racks. Heaven forbid that the racks be overdone! Some chefs recommend cooking the stuffing separately and putting it back into the crown once it’s been roasted separately. You can cook the racks at a high temperature, which is the method for those who live dangerously, since it only takes a few minutes for the whole thing to move from perfectly done to overdone. There’s also a risk the meat won’t cook evenly, since there are thicker parts and thinner parts. Your more cautious and scientific chef will cook the crown at a slow temperature for a long time, finishing it off with a blast of searing heat under the broiler.

Ceremonial entry into the dining room with the crown is a must. At Christmas, all meats are brought in to the “Boar’s Head Carol”, but at Easter the entry soundtrack is “Worthy is the Lamb” from Handel’s Messiah. (It’s OK to play a recording rather than hire a choir, orchestra and conductor — though if you can afford it and have room, why not?) Did you know that Handel originally composed the Messiah for Easter? I didn’t, though it makes perfect sense when you think about it.

There are some foods, like bread, wine, salt and lamb, that are never only food. They express our relationship with nature, with sacrifice, with the nourishing providence that keeps our cells ticking and our hearts beating. Worthy is the Lamb that was slain, and hath redeemed us to God by his blood… Yet they aren’t mere symbols, devoid of individual substance. They are what they do. They feed, they die to give life, they unite those who share them in the bond of friendship. It’s only grateful to fashion them into things of beauty and delight — fine vintages and crown roasts. Let’s drink to the lamb.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2022 World edition.