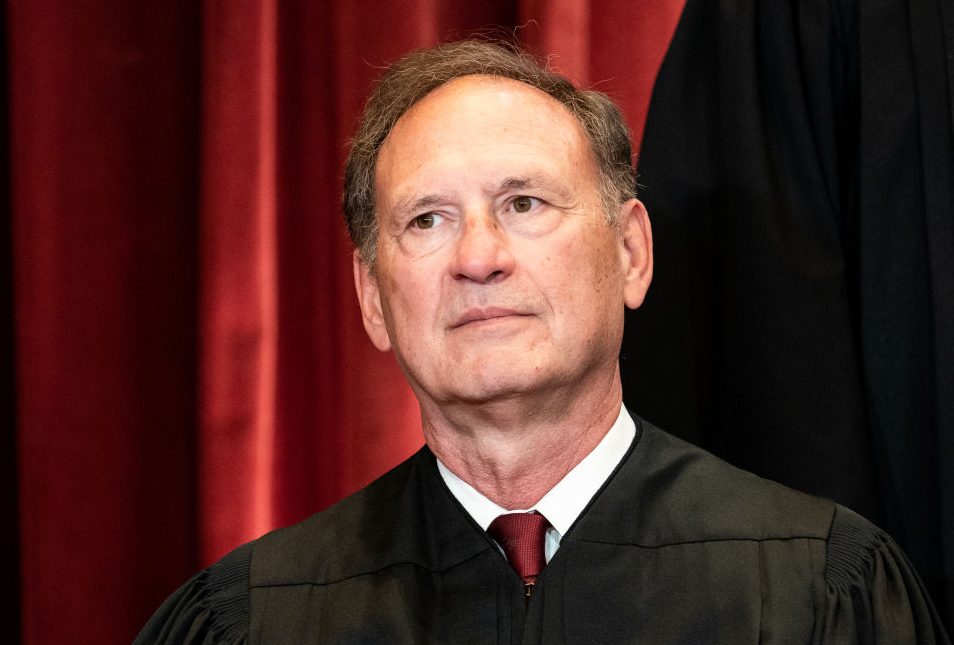

Justice Samuel Alito’s leaked majority opinion in this Supreme Court term’s marquee abortion case, Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization, ought to be applauded by pro-lifers. In many ways, the opinion represents an epochal triumph for the conservative legal movement that I, despite being a clear part of, have often been quick to criticize.

If Alito’s five-justice coalition holds — and it remains an “if” until the moment the opinion is formally released — then the decades-long architects of the movement will deserve credit for finally fulfilling one of the movement’s raison d’êtres, the overturning of the odious Roe v. Wade decision.

Alito’s leaked opinion is remarkably straightforward in its legal analysis, and compellingly weaves together many of the main analytical tools that have long dominated the practitioners and jurists (if perhaps not necessarily scholars) who comprise the broader originalist firmament.

On the actual doctrinal issue that allegedly undergirded Roe, the 14th Amendment doctrine of so-called “substantive due process” (and that doctrine’s allegedly implied “right to privacy” subcomponent), Alito largely endorses the framework from the late Chief Justice William Rehnquist’s majority opinion in 1997’s Washington v. Glucksberg. Just as Rehnquist in Glucksberg rejected assisted suicide as an implicit “liberty” protected by the Constitution because it is not “deeply rooted in the nation’s history” and traditions, so too does Alito reject Roe’s assertion of constitutional protection for abortion in his leaked opinion.

Alito’s approach to “substantive due process” is reminiscent of the decades of railing against the doctrine and its excesses by the late Justice Antonin Scalia, a founder of the modern conservative legal movement. What’s more, in keeping with the framework of his majority opinion in the 2010 landmark Second Amendment case McDonald v. City of Chicago, Alito eschews opening up the (long dead) can of worms presented by the 14th Amendment’s Privileges or Immunities Clause — likely for the very simple reason that such an argument was not briefed.

What’s more, Alito’s analysis of stare decisis in Dobbs, with its pragmatic focus on numerous factors such as the “reliance interests” at stake, is also reminiscent of Scalia’s approach, which he most clearly outlined in 2009’s Montejo v. Louisiana. That stare decisis approach stands in contrast with the more doctrinaire position of Justice Clarence Thomas.

The Dobbs result, then, if it holds, is of course worth celebrating. Countless unborn children will be spared the fate of an abortionist’s knife.

Still, the opinion, including the doctrinal analysis and the frameworks deployed therein, can only be described as “normie.” It will culminate a half-century of originalist braggadocio that the Constitution is “silent” on the issue of abortion. By de-constitutionalizing this contentious issue and devolving it back to the states, Alito’s opinion takes pro-lifers closer to the promised land. But his opinion is not the promised land itself.

The real end goal, as I and many other pro-lifers have argued, is for federal protection of all unborn human life: for constitutional personhood.

The legal argument for this is straightforward. The 14th Amendment’s Equal Protection Clause, which forbids any state from “deny[ing] to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws,” was understood to include both born and unborn “person[s].” The upshot is that, while a state legislature can make reasonable distinctions in its criminal code’s homicide statutes, a state’s criminal code cannot effectuate a discriminatory regime that solely protects those who are born but not those who are unborn. Put another way, if a state bans homicide, then it has to generally ban abortion.

As the esteemed natural law philosopher John Finnis and well-known Princeton University professor Robert P. George put it in their amicus brief in Dobbs:

[T]he Fourteenth Amendment, like the Civil Rights Act of 1866 it was meant to sustain, codified equality in the fundamental rights of persons—including life and personal security—as these were expounded in [Sir William] Blackstone’s Commentaries [on the Laws of England] and leading American treatises.

The Commentaries exposition began with a discussion (citing jurists like Coke and Bracton) of unborn children’s rights as persons across many bodies of law. Based on these authorities and landmark English cases, state high courts in the years before 1868 declared that the unborn human being throughout pregnancy “is a person” and hence, under “civil and common law,” “to all intents and purposes a child, as much as if born.”

Although the Court could one day implement this proper understanding of the Equal Protection Clause, the more promising path would be for Congress to use its 14th Amendment Section 5 enforcement power to affirmatively legislate this. Put more simply, the ideal way to ban abortion in America, at some point in the hopefully not-too-distant future, is for Congress to simply enact a national ban. There is nothing stopping Congress from passing such legislation tomorrow, and there is definitely nothing stopping Congress from passing such legislation after Roe’s forthcoming demise in Dobbs.

And as strong as the legal argument for constitutional personhood is, the moral argument is even stronger. The fundamental question of the humanity of the unborn child in this decade, much like the fundamental question of the humanity of the black man in the 1850s, is a matter that cannot be left to “might makes right”-style majoritarian democracy. Because here, as in the 1850s, there is an inescapable, underlying biological and moral truth that cuts to the heart of the matter: the unborn child is a distinct member of the human species, and deserves legal protection.

As Abraham Lincoln famously argued in his 1854 Peoria speech, the relevant question is “whether a Negro is not or is a man.” So, too, is the relevant question in the abortion debate whether the unborn child is not or is a person. We happen to know the answer to that question.

Those defending the imperative to protect life nationally, in appealing to inescapable truth — the very “first principles” Alexander Hamilton referred to in The Federalist No. 31 — stand on the side of Lincoln. By contrast, those who are merely content to let abortion play out democratically in the states are implicitly hearkening back to Stephen Douglas, who time and time again in his 1858 debates with Lincoln appealed to an overarching imperative of “popular sovereignty” in the Western territories. Douglas’s position then, much like the “states’ rights” view of abortion today, was to be content to avoid the truth at the heart of the matter, and to simply defer to plebiscitary majorities — notions of “right” and “wrong” be damned.

Pro-lifers today should stand with Lincoln, not Douglas. And in that sense, Justice Alito’s leaked handiwork in Dobbs makes for an admirable start — but no more than that.

Josh Hammer is Newsweek opinion editor, host of “The Josh Hammer Show,” a syndicated columnist, and a research fellow with the Edmund Burke Foundation. Follow him on Twitter @josh_hammer.