By her own account, Eudora Welty had an idyllic childhood. Born in 1909 on Congress Street, two blocks from the state capitol in Jackson, Mississippi, Welty spent her early years playing with friends from school, reading voraciously and riding her bicycle to the local store to pick up some flour or eggs for her mother and, of course, a treat for herself.

Her father, who was devoted to his wife and children, advanced from a cashier to vice president at Lamar Life Insurance before his daughter had finished high school. He had, as Welty put it, a love for “all instruments that would instruct and fascinate,” including a toy train set, a telescope and a folding Kodak, with which he would teach the young Eudora the pleasures of photography.

There was also a car — a “five-passenger Oakland touring” — which the family drove to Ohio to visit her father’s family and West Virginia to visit her mother’s shortly after World War One. Welty writes about the trip in One Writer’s Beginnings. Her father’s family were quiet, religious Swiss Germans, and her father himself was “stable, reticent, self-contained, willing to be patient if need be, and, in all he said, factual.” Her mother’s family were fiercely independent, full of song and stories, like the mountains themselves. When her mother married her father and the two moved to Mississippi, her mother’s family “never really got over her absence from home,” Welty writes. “I don’t think she ever really got over it either.” The trips, Welty writes, “were wholes unto themselves. They were stories. Not only in form, but in their taking on direction, movement, development, change.”

The Optimist’s Daughter, Welty’s most autobiographical and accomplished novel, which was published fifty years ago, opens with a trip. Laurel, who is based on Welty, has just arrived in New Orleans on a plane from Chicago. Her father, Judge McKelva, is to undergo surgery for a detached retina. His second wife, Fay, is there. She is much younger than the judge, crass, boisterous and self-absorbed. He married her unexpectedly several years after his first wife died.

Judge McKelva dies shortly after the surgery when Fay, who wants to go out on the town to celebrate her birthday, shakes the judge, frustrated at his slow recovery. The two women bring his body back to Mississippi by train, and much of the novel is about Laurel trying to understand why her father would marry such a woman as Fay, while also coming to terms with the death of her mother and her own husband, who died in World War Two, whom she never really mourned.

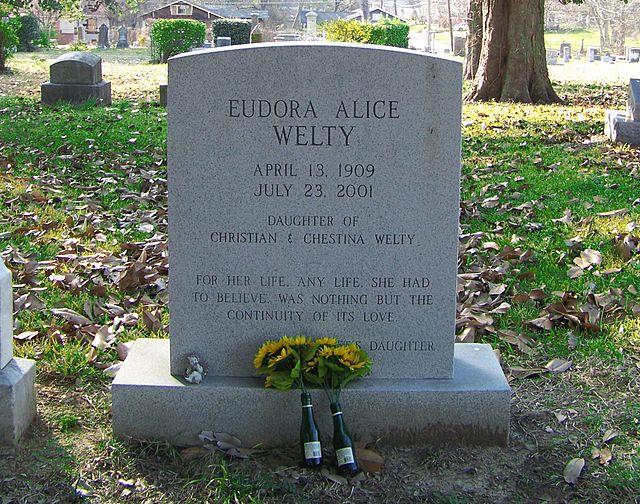

Welty herself never married, though she did have a serious relationship with one John Robinson, but he never proposed because he was likely a homosexual. Her father, Christian, died when she was twenty-two, and the novel was actually written in memory of her mother, Chestina Andrews Welty (the C.A.W. of the novel’s dedication), who died in 1966. Her younger brother Edward died just four days after Chestina from a brain infection. Her other brother, Walter, had died in 1959.

The novel is, in many ways, about the death of surviving. In a key scene — Laurel’s Lear-like “dark night of the soul” — she remembers her deceased husband, mother, and father, and weeps “in grief for love and for the dead.” Everyone she has ever loved is dead, and she realizes that her devotion to their memory had “sealed away” love into a stasis of “perfection.” That “perfection,” of course, is ironic, since her memories of her loved ones were incomplete and subjective, and it was this devotion to their memories that had kept Laurel herself in the past and shut out from the living. To live she must let go of those she loves, of the past, which is also a kind of death. Laurel realizes at the end of the novel that a more faithful kind of memory “lived not in initial possession but in the freed hands, pardoned and freed, and in the heart that can empty but fill again.”

The novel reminds us that memory must be given its due. The dead will always be with us, and there is no full recovery from losing those we love. But giving up on the present to devote oneself to the memory of the dead distorts both the dead and the living.

Welty won the Pulitzer Prize for the novel in 1973 — her only Pulitzer. It is a rich and daring work, written in a straightforward style and narrative that few novelists today would risk out of fear of appearing ordinary. Welty had no such fear, knowing that great art, like profound ideas, appears to be the simplest of things on the outside but contains a whole world.