One lunchtime in May, the sixth floor of a restored warehouse on Manhattan’s Ninth Avenue buzzed with the sound of lingering lunch dates, pandemic-postponed reunions and the erratic clatter of computer keyboards beneath the inspired fingertips of creatives and those moonlighting as such.

Just beyond the reception desk a gaggle of bespectacled, chino-clad men congregated. In suede sneakers and made-to-look-worn corduroy jackets, they clutched Scandi-chic satchels and laptop bags, poised to pounce on the next available artfully upholstered chair. Even one of the sumptuous velvet sofas would do.

Next door, in the dining area, waiters weaved in and among patrons like figure skaters, determined not to risk their precious tips by spilling a drop of Bloody Mary or chai latte. Six-feet rules, it seemed, only existed as a vague memory, distorted by the rabble’s excitement at being back and, most importantly, at being seen again.

The new normal looked a lot like the old normal. Or at least it did at Soho House’s Chelsea outpost during a weekday lunch hour. While much of New York’s hospitality sector has contended with — at best — a sluggish stop-start recovery from Covid, the city’s private members’ clubs have rebounded with verve.

Founded in 1995 by current chief executive Nick Jones, UK-based Soho House is a relative veteran among the newer breed of private members’ clubs and has enjoyed market dominance for some time. More recently, a crop of competing institutions have started to vie for a slice of the prestige pie across a host of US cities, offering members refined, real-world antidotes to the lawlessness and bad manners of life online.

Casa Cipriani, a hotel and private club in a beaux-arts-style erstwhile ferry terminal, opened its doors in lower Manhattan last summer. A little further north Zero Bond, which started welcoming members a year earlier, regularly crops up in the tabloids as a preferred date spot for Kim Kardashian, a favorite hangout of Mayor Eric Adams and the site of Elon Musk’s Met Gala afterparty. Meanwhile, NeueHouse, founded in 2011 and describing itself as a “private work and social space for creators, innovators and thought leaders,” plans to expand its network from Los Angeles and New York to Miami.

Each club makes a slightly different pitch for members. But ultimately, all share the same implicit promise — a destination for self-styled global citizens searching for the Holy Trinity of success in the twenty-first century: brains, bucks and beauty.

“I just love the idea of having a place to go where I know that the service will be good, the company interesting and the atmosphere cool,” says Peter, a twenty-nine-year-old graduate student who applied for membership to Casa Cipriani in April. He’s still waiting to hear back. “It’s a bit daunting,” he admits. “They’re obviously deciding whether I’m worthy — whether I’m successful enough to be one of them.”

As for Soho House — of which, full disclosure, I have been a member for three years — 2022 appears to have brought a surge in demand for one of its coveted black membership cards despite all the glitzy new kids on the block. In March, it opened a forty-seven-bedroom hotel and club in Nashville. Globally, Soho House now has thirty-five houses as well as a clutch of spaces. As of the first quarter of 2022, the houses had just over 130,000 members, up more than 17 percent since the same time a year ago, according to company filings. Another 79,000 people are currently on the waitlist for all its houses and spaces.

“I’m not surprised,” Anna, a forty-year-old copywriter from Oslo, tells me. She moved to New York eight years ago and accounts for one of tens of thousands of hopefuls. “It’s the coolest office, the nicest bar and a really good restaurant all wrapped in one,” she says. “Of course I want to be in the Soho House crowd.”

There’s certainly more to the appeal of these clubs than the fancy cocktails and soup-of-the-day Anna hopes to enjoy. Might the uptick in club openings and applications across New York and beyond tell us something profound?

Frenchie Ferenczi, a New York-based entrepreneur who used to work as head of community for The Wing, a women-focused club founded in 2016 with offices in New York, San Francisco, West Hollywood and Chicago, says that “after that you get thrust out into the real world and finding your people — especially in large cities — feels overwhelming and burdensome… There’s something to be said for the fact that, by just being allowed into the same space, you have a foundation of trust and respect. The same thing wouldn’t happen in, say, a subway car.”

On a more fundamental level there is, of course, the human desire for belonging. In 1995, social psychologists Roy Baumeister and Mark Leary published research establishing the importance of human relationships to a happy and healthy life. Building on work by Sigmund Freud and Abraham Maslow, they compared the need to belong to the need for enough food and a safe place to live. Since then, a considerable amount of research has shown that humans develop a sense of belonging when we feel connected to others, especially when we think we share their life experiences, perspectives and goals.

Decades ago, the church might have offered many of us that haven. But according to the Pew Research Center, at the end of last year almost 30 percent of Americans considered themselves religiously unaffiliated, up about 10 percent from a decade ago. And the demographic cohort eschewing religion is the same as the cohort that’s flocking to new private members clubs: millennials.

“People are intrinsically groupish animals,” explains Jay Van Bavel, an associate professor of psychology and neural science at New York University. “We gain a sense of belonging and identity from group membership,” he tells me. “But groups fill more than our need for belonging; they can also provide a sense of distinctiveness and status. This is why people are drawn towards groups that feel exclusive or unique.”

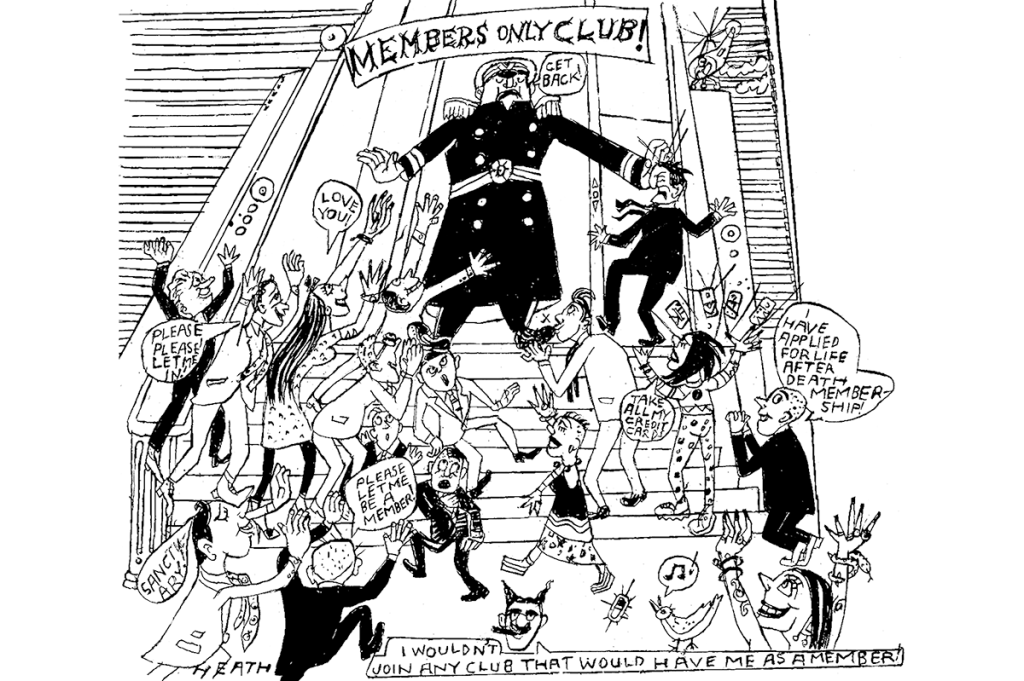

Dig a little deeper on this latter point and it might even reveal a blustering hypocrisy when it comes to members of these newer clubs: the cosmopolitan, cultured and concerned citizens of contemporary clubland. From their perches of privilege they might talk the talk on socioeconomic equality and racial equity, but they simply can’t resist being part of the elite, hoping a membership card might set them apart.

And Van Bavel suspects that there might also be a less obvious catalyst behind a swelling desire to be a member of a club: social media. “Now that roughly four billion people are on social media, some might want to offset that kind of public exposure with membership in more exclusive groups — whether that means a private club or just hanging out with our closest friends,” he explains. “These groups provide a space where people often share a set of beliefs and social norms that make interactions easier and more friendly.”

Venessa Paech, who researches communities at the University of Sydney, agrees. “People crave settings where they can influence culture and social norms more intentionally around their shared values or purpose,” she tells me. Private clubs, her logic suggests, might offer just that.

As is the case with so many things, the pandemic probably exacerbated this need for belonging. After months of social distancing and isolation the thrill of real-life company may be irresistible. “Human connection is how we access belonging and help make sense of ourselves and the world,” Paech says. “This has been missing for many over the last few years, leaving us both hungry to gather in person and anxious about re-entering vast, socially noisy environments.” She says that private groups offer an ideal middle ground.

Finally, amid the drumbeat news cycle of war, new virus variants, rising crime rates across many cities and an economy threatening to topple into recession, there’s a sense I get, as I talk to members and those sitting anxiously on the waitlist, that clubs offer an element of escapism, a chance to float above it all.

America might like to think of itself as a classless society, but Americans also delight in the quaint manifestations of Britain’s visibly entrenched one, by bingeing TV shows like Downton Abbey and gobbling up coverage of the Queen’s Jubilee celebrations. Members of New York’s most coveted contemporary members’ clubs would probably scoff at comparisons to Gilded Age equivalents, let alone stuffier antecedents in London. Back then society was myopic, sexist, racist! We, by contrast, care about social justice. But can clubs really escape the class baggage? Does it really just boil down to proving you’re a cut above?

When you’re fumbling for your Metro card while doing your utmost to avoid a homeless person’s pleas for a dollar, your membership card — that discreet emblem of success and exuberance — might catch your eye, serving as a merciful reminder that herbal tisanes served in fine bone china and the lobster roll lunch special are just a couple of subway stops away. And when you walk through those doors and score a spot on that sumptuous sofa, you might even forget for a second that you’re the kind of person who would even get the subway in the first place. Reality’s outside. This is clubland.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2022 World edition.