This year marks the 400th anniversary of the birth of Jean-Baptiste Poquelin, better known as Molière. While it was decided that Molière would not be inducted to France’s Panthéon — he is not a republican and so is not eligible — the playwright has been celebrated in other ways in his home country.

In the New York Times, Laura Cappelle reviews a handful of “wildly different” productions of his work in Paris and across the country: “While the Comédie-Française, whose 2022 program is entirely devoted to Molière, has invested in dark, offbeat productions, ‘Molière Month,’ a yearly theater event run by the city of Versailles, has delivered traditional gowns and breeches, to slightly dull effect.”

Of the productions under review, she prefers Christian Hecq’s “stunning” production of The Bourgeois Gentleman in which he also stars:

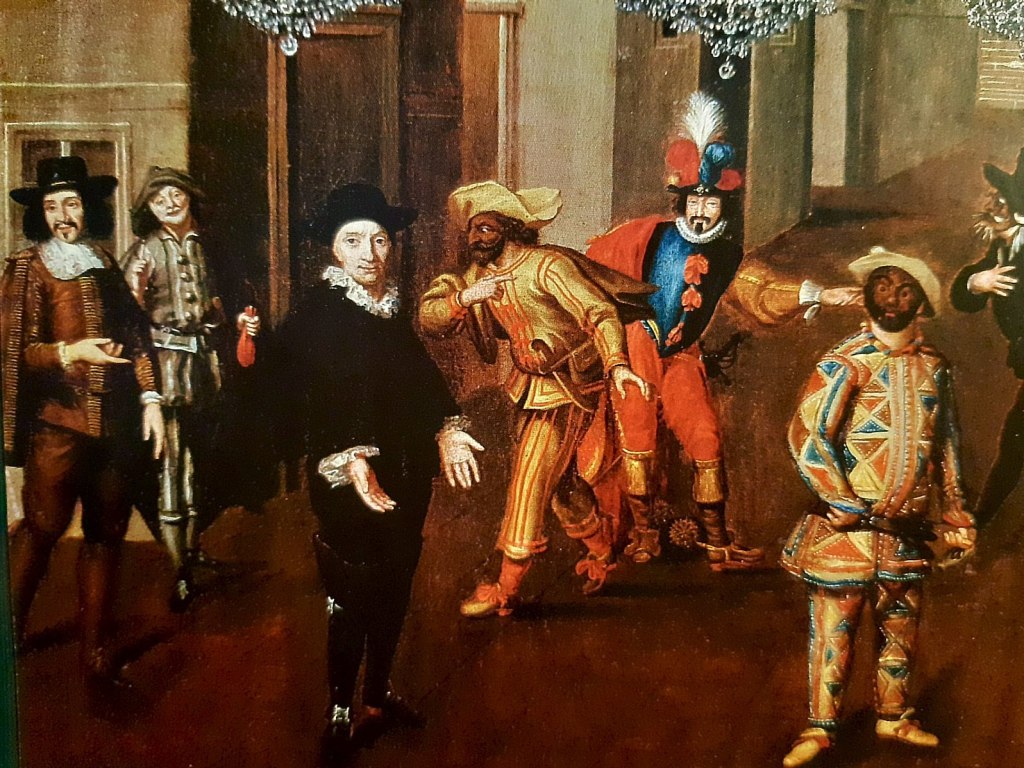

“The Bourgeois Gentleman” arguably cements Hecq’s place as one of the Comédie-Française’s most category-defying and valuable artists. With his gruff voice, small frame and clownlike gift for physical exaggeration, he could easily have been typecast as a commedia dell’arte servant. Yet his emotional range — willing to be thoroughly ridiculed one second, the picture of relatable heartbreak the next — is evident in his Monsieur Jourdain, the clueless bourgeois who wants nothing more than to be accepted as an aristocrat.

And together with Lesort, he has emerged as part of a duo of stage magicians, deploying old-fashioned tricks and visual imagination. In “The Bourgeois Gentleman,” that means flying swords, a life-size embroidered elephant and animated goat heads that sway to one of the songs. Since this play also started life as a comédie-ballet, the original score, by Lully, has been revisited here by Mich Ochowiak and Ivica Bogdanic, in a vigorous style inspired by Balkan music. The costumes, by Vanessa Sannino, are luxuriously eccentric: Françoise Gillard, in the role of a marchioness, looks like a fabulous golden beehive.

But there is little to mark the work of one of the greatest playwrights in the world outside France. In the Guardian earlier this year, Michael Billington complained that “in parochial Britain, his quatercentenary appears to be going signally and shamefully uncelebrated.”

The same is the case in the States, but you can always read his plays. I recommend Richard Wilbur’s excellent translations, which have just been published in a two-volume set by the Library of America.

In other news

Amazon allows e-book customers to “cancel an accidental book order within seven days,” but some authors are arguing that customers are using the policy to read and return books to avoid paying for them:

Reah Foxx, a book lover from Louisiana, started a petition to change the policy after seeing “life hacks” circulating on social media that teach readers to abuse the Amazon return policy and read for free. To date, the petition has garnered almost 70,000 signatures. Kessler said prior to the “read and return” trend, she would normally have one or two book returns a month, something she attributed to genuine accidental purchases. Now, she sees entire series of hers being returned.

Timothy Steele reviews Robert B. Shaw’s new collection of selected poems: “Shaw writes in a wide range of verse forms and genres, but we can distinguish several fundamental characteristics of his style. For one thing, he practices meter and storytelling with unaffected dexterity.”

Todd Longstaffe-Gowan on one of England’s most eccentric gardens, Lady Broughton’s imitation glacier: “In the early 1860s the celebrated American horticulturist and landscape gardener Henry Winthrop Sargent, who had a ‘taste for horticultural oddities and freaks,’ made a special pilgrimage to Hoole House in Cheshire to catch a glimpse of a garden which he had longed to see for over a quarter of a century.”

Why is no one going to see The Northman?

The American director Robert Eggers has had an auspicious early career. His first two movies were smash hits in the arthouse world: 2015’s The Witch, which launched the career of Anya Taylor-Joy, and 2019’s The Lighthouse, which starred Robert Pattinson and Willem Dafoe. Both films were produced on small budgets by indie powerhouse A24, and both have already achieved a kind of cult status among horror buffs and cinephiles alike. So when news broke that New Regency was offering the auteur director a budget of around $70 million for his third film — a Viking revenge epic starring Alexander Skarsgård, Taylor-Joy, Ethan Hawke and Nicole Kidman — movie geeks went wild. Just not quite wild enough to buy actual tickets, apparently.

Blade Runner at forty: The 1982 “replicant hunting classic remains the benchmark for everything that came after.”

Charlotte Allen reviews a cultural history of the Nile: “A new book by Candice Millard, a former writer and editor for National Geographic and the author of bestselling accounts of Theodore Roosevelt’s Amazon adventures and Winston Churchill’s youthful exploits during the Boer War, is thus a welcome introduction for new readers to the captivating story about the great river.”

Naomi Schaefer Riley reviews Stephen Eide’s new book on the history of homelessness in America:

Though it is certainly true that population exodus during COVID and the retreat of law enforcement in the wake of the George Floyd protests contributed both to public disorder and violence in much of the country, the origins and expansion of homelessness in particular have a much longer and more complex history. (For instance, places like Detroit that have a much higher rate of crime also have much lower rates of homelessness.) Stephen Eide’s new book, Homelessness in America: The History and Tragedy of an Intractable Social Problem, sheds new light on this issue.

Tim Stanley reviews Michael Warren Davis’s The Reactionary Mind: Why “Conservative” Isn’t Enough: “This is a stonkingly good book, well-written and funny. It’s also quite mad, but that’s what makes it so compelling.”

And I revisit the columns of Maxim Gorky:

In these columns, which were collected as a book called Untimely Thoughts and published in 1918 (and just as quickly suppressed), Gorky argued that a cultural revolution needed to take place in Russia before a material one. The masses lived for the immediate moment and were incapable of thinking, acting freely and living virtuously. As long as they had a few pleasures, he argued, they were happy to live under the control of the monarchy or state. Gorky saw, too, that party leaders were just as hungry for power as the aristocracy and that what would follow a revolution would not be a new world but another version of the old one.