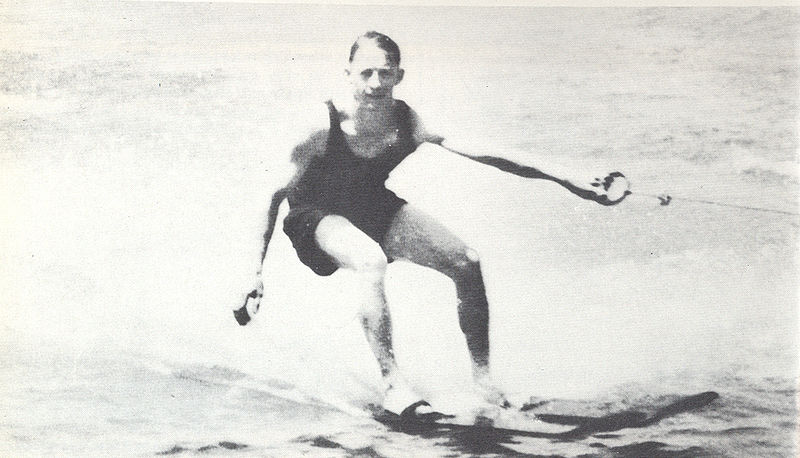

In the Smithsonian, Sarah Kuta writes about the man who invented waterskiing 100 years ago. His name was Ralph Samuelson. He lived in Minnesota and wondered one winter if you could ski on water the way you could on snow. At eighteen, he made his own skis and had his brother pull him on his boat:

He unsuccessfully tried snow skis and barrel staves before realizing that he needed something that covered more surface area on the water. The ever-resourceful Samuelson went to the local lumberyard and found two eight-foot-long, nine-inch-wide pine boards, wrote Sports Illustrated’s Jim Harmon in 1987. Using his mother’s wash boiler, he softened one end of each board, then clamped the tips with vises so they would curve upwards. He affixed leather straps to hold his feet in place and acquired 100 feet of window sash cord to use as a tow rope. Finally, he hired a blacksmith to make a small iron ring to serve as the rope’s handle.

In the days that followed, Samuelson tried several different approaches. In most of his attempts, he started with his skis level with or below the water line; but by the time his brother got the boat going, Samuelson was sinking.

Finally, he tried raising the tips of the skis out of the water while he leaned back — and it worked. As his brother steered the boat, which was powered by a converted Saxon truck engine, Samuelson cruised along behind him. To this day, this is still the position that water skiers assume.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]There is something, isn’t there, about gliding on the surface of the water on skis, in a boat, or on a surfboard? Here is a short documentary of Ralph Samuelson produced by the Lake City Historical Society. Samuelson began performing tricks on his skis, and crowds as large as 1,000 people came out to watch him. In 1925, he skied behind a plane. Read more about those earlier years on skis in this 1987 Sports Illustrated article on Samuelson.

In other news

Erica Wagner reviews the second volume of Robert Crawford’s biography of T.S. Eliot:

Eliot plays his cards close to his chest: personally, politically. This can make him a tricky biographical subject in the 21st century, but Crawford — correctly — refuses to judge. “I try to present Tom Eliot’s life and work without undue moralizing, letting readers reach their own conclusions.”

The always interesting Ted Gioia explains why medieval cities hired street musicians to work as first responders:

Consider the peculiar law in London in the late medieval period, that required each entry gate into the city to keep a musician on duty. This could be a dangerous job — city gates were where attackers and other threatening outsiders first appeared. It’s like border patrol nowadays, but they gave the job to musicians. As strange as it sounds, musicians took charge of many essential services back then.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Why do people go mad in crowds? Dion J. Pierre reviews William J. Bernstein’s book on the phenomenon:

In a parade of mass manias the book rehearses, some famous stories and some obscure, we begin to see the contours of an explanation of why this phenomenon persists, and these two serve as the best examples of the two most persistent types of mass mania: religious and financial.

A landscape architect shares his plans to make the area around Notre Dame more pedestrian friendly:

His ambitious plan, which garnered the unanimous support of the jury, includes more trees, a clever cooling system for the large area in front of the cathedral during heatwaves and a new reception center and archaeological museum in the now-abandoned car park underneath the main square opening on to the banks of the Seine.

Speaking of cathedrals, check out this story about climbers who clean and repair the stonework of Salisbury Cathedral in Wiltshire:

“It’s hard work but fun,” said Philip Scorer, who is leading a team of climbers spending the summer assessing and repairing the façade, as well as the steeple and parts of the tower. “Occasionally it gets scary but as soon as you’re concentrating on the work, you’re fine. I’ve been doing this for almost twenty years so if I’m not used to it then I’m in the wrong trade.”

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]In June 1863, a caravan of Union soldiers became lost while transporting a shipment of gold. Their wagons were eventually found, as well as a few human remains, but no gold. In 2017, the FBI got involved. Chris Heath tells the story in the Atlantic.

Congress clearly has little interest in fixing Social Security. What happens when the program runs out of money? Sita Slavov reviews R. Douglas Arnold’s Fixing Social Security.