There are so many examples of narcissism-on-steroids that litter Rolling Stone magazine founder Jann Wenner’s memoir that it’s difficult to point out just one. But the following is typical: in 2001, Wenner was invited to a recording session for his friend Mick Jagger’s solo album Goddess in the Doorway. Wenner, long out of practice in writing for his magazine — clear prose was never his forte — submitted a review to his editor, who, knowing of the friendship, gave the album four stars. Wenner intervened, bumping it up to five stars, and reflected: “There was some snickering [in the office] about being on Mick’s leash, but so what, and what if I were?”

Wenner’s torturously long memoir is a very bad book. I can’t imagine the demographic that publisher Little, Brown & Company envisioned when it was commissioned. The dwindling number of people who fondly remember Rolling Stone’s remarkable run from 1967-76 (the magazine began its descent when Wenner cozied up to Jimmy Carter and his aides) likely don’t want to read such hagiography. Perhaps it’s a favor — Wenner collected chits from people in the music and book industries like kids used to hoard baseball cards — and the company is willing to absorb the loss on what’s plainly a vanity project.

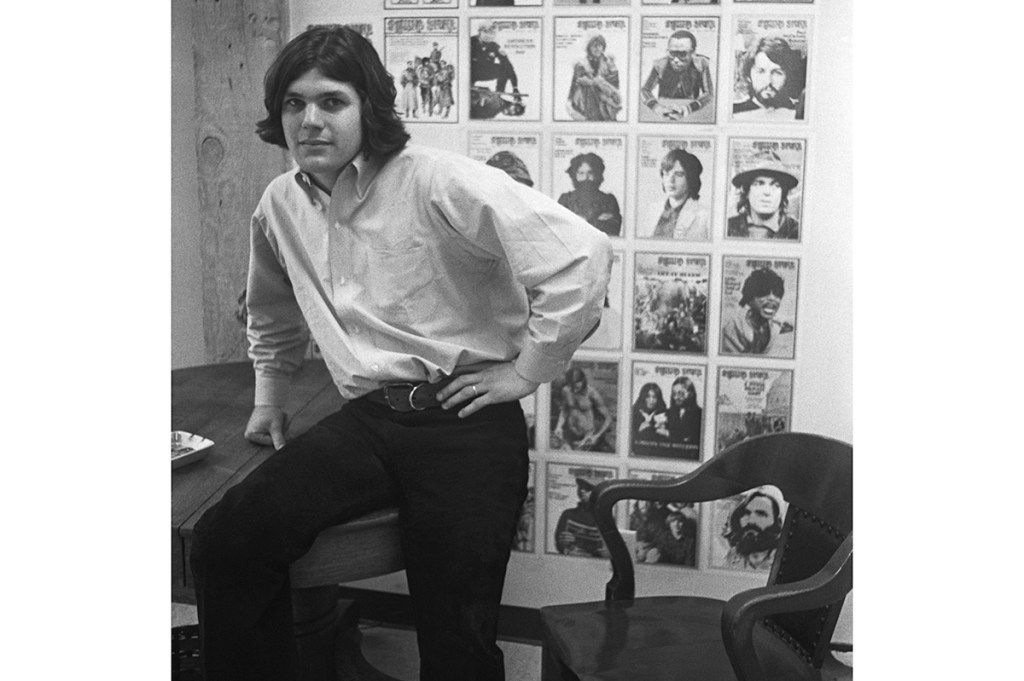

My guess is that the seventy-five-year-old Wenner, like his heroes Bob Dylan and Keith Richards, is trying to control his legacy before he dies. But there’s a problem: while Wenner is justifiably praised for launching one of the most influential periodicals in the second half of the twentieth century — along with, by my reckoning, Playboy, the Village Voice and Spy — the product and its writers were always far more fascinating than the proprietor himself, who, because of his lust for meeting and befriending “stars,” first musical and later political, was roundly ridiculed in the business. That happens, to a lesser degree, with all flamboyant publishers, but 592 pages of Wenner flitting from topic to topic (I’m sure he had an assistant gather old copies of RS to jog his memory), with no discernible motive other than to assert his own fabulousness and importance, is embarrassing — though I doubt the author is capable of embarrassment. Wenner weeps at the drop of a drumstick — no real flaw — and celebrates that characteristic.

There are already two worthy books about the history of Rolling Stone magazine: Robert Draper’s superb Rolling Stone: The Uncensored History, published in 1991, many years after the magazine shed its vibrancy; and Joe Hagan’s comprehensive Sticky Fingers from 2017 (Wenner originally gave Hagan full access before the two had a falling out). The biweekly’s history is a worthy topic; Draper and Hagan capture the behind-the-scenes drama.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]In reading Like A Rolling Stone, however, I wasn’t sure if Wenner outright lied or just embellished events in his life. For example, as a freshman at Berkeley in 1963, upon hearing the news of John F. Kennedy’s assassination, Wenner claims he took to his bed for four days, mourning “our beautiful young president.” At that time, universities weren’t plagued by today’s ruinous liberal climate, and the workload was rigorous. That Wenner, a smart young man, would lay low for four days stretches the imagination, although that anecdote isn’t as noxious as him, skipping to 2008, describing his sons as “godlike” as they emerged from the surf in Hawaii.

Separating the man from his product, Rolling Stone in its heyday was extraordinary. Rock criticism and the burgeoning hippie culture were in their infancy, and RS was the place to turn. What other magazine would have a short column called “Dope Notes” or run 20,000-word articles on groupies, Altamont, Woodstock, the cult of Charles Manson, the Chicago Seven trial, the Patty Hearst kidnapping or a cover (1970) about the United States with the headline “A Pitiful Helpless Giant”?

In 1972, like hundreds of thousands, I waited for the latest installment of Hunter S. Thompson’s brilliant “Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail,” a series that (along with accompanying articles by Timothy Crouse and illustrations by Ralph Steadman) redefined presidential coverage. By all accounts, Wenner did hold the mercurial Thompson’s hand through his deadline — even as the author drank and ingested drugs all the while — and that’s no small accomplishment. So many writers and artists rose to prominence at Rolling Stone, including Joe Eszterhas, David Felton, Lester Bangs, Howard Kohn, Jon Landau (later Bruce Springsteen’s manager), photographer Annie Leibovitz, Greil Marcus, Chet Flippo and Paul Scanlon. In addition, Wenner serialized Tom Wolfe’s Bonfire of the Vanities and sent P.J. O’Rourke all over the world. In a rare instance of humility, Wenner admits he never had an acute business sense, and that led to an enormous editorial budget: sometimes for the good, sometimes merely profligate.

But the above is well-documented. In Like A Rolling Stone, the reader is attacked by name-dropping on almost every page. He refers to rock friends as Bob, Mick, Keith, John, Boz, Bette, Bruce — no last names necessary. Wenner pounds away at his advocacy for combating climate change, yet that bloviating is interspersed with recollections of his private planes, palatial homes and gas-guzzling vehicles. I’d bet his “carbon footprint” is even larger than John Kerry’s, the 2004 presidential candidate whose campaign Wenner was allegedly a major player in, just as he was in Al Gore’s in 2000.

After reading all this drivel, it should come as no surprise that Wenner worshipped the Kennedys and was close with Jackie, Caroline and John Jr. (“a brother”). Nonetheless, the late president’s son was a bit squeamish when Wenner revealed his homosexuality and took up with (later marrying) model Matt Nye, after divorcing his wife Jane, who had helped him raise part of the $7,500 stake for founding Rolling Stone in 1967.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]After the Hagan book, Wenner obviously wanted the last word. Instead, he has tarnished his reputation with outrageous self-regard, instead of letting his considerable accomplishments stand as his legacy. It’s said more books about Rolling Stone are in the works, one by David Weir, but, at this point, count this former subscriber out.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2022 World edition.