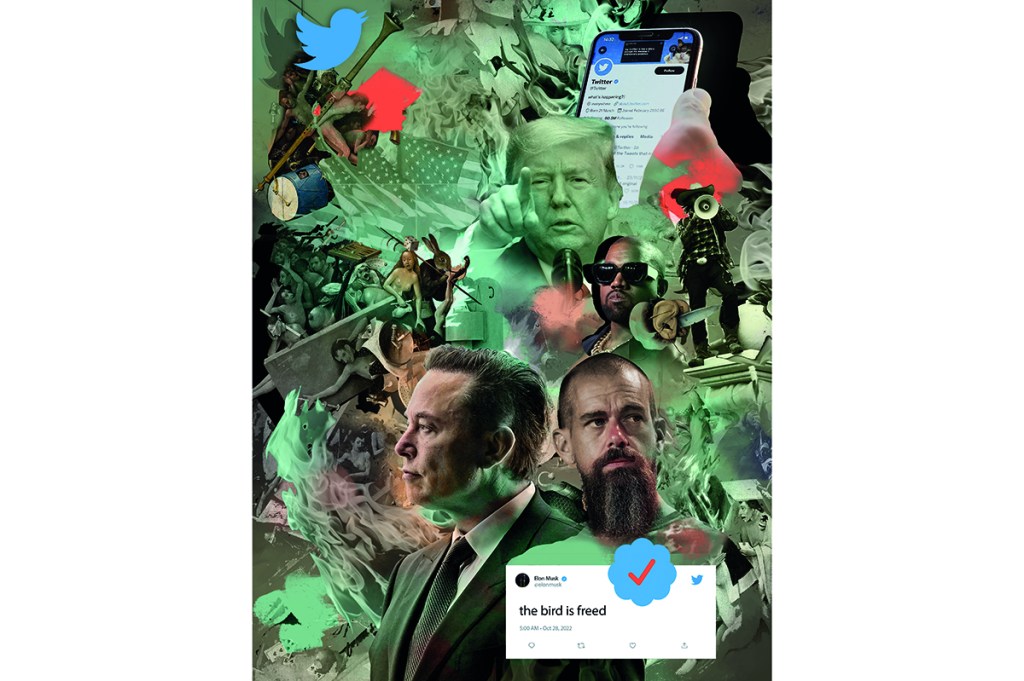

A philosopher once famously said that Hell is other people. What the world has learned from Twitter is that Hell is other people’s opinions. It’s no wonder, then, that when Elon Musk came bounding into Twitter headquarters in late October — after changing his Twitter bio to “Chief Twit” — a popular response, on Twitter and off, was, “welcome to Hell.”

When Musk, in an open letter to Twitter advertisers, wrote that he doesn’t want the site to become a “free-for-all hellscape,” he touched a debate concerning a much larger issue — balancing free speech against the need to keep hate, propaganda and manipulation out of public forums, particularly digital ones that can spread malicious content around the world instantly. At present, Twitter’s top-heavy approach of banishing accounts that the site’s moderators deem wrongthink, which often include legitimate criticisms of power, while simultaneously allowing algorithms that elevate engagement-driving invective, has created nothing so much as a Boschean panorama.

The furor resulting from Musk’s acquisition of Twitter has followed these recognizable lines. Free-speech absolutists, generally from the right, are now singing Musk’s praises while, on the left, advocates of controls and limits on speech are expressing serious concerns, in some cases revulsion. Behind all the consternation and celebration, however, lurks the question of whether Musk can actually fix the broken institution that Twitter has become. And whether or not he can strike the balance needed for the platform to serve as the town square he says he wants it to be. Getting that right could prove as complicated as rocketing a bunch of quibbling human beings to Mars.

Even more worrying for Twitter is the fact that a group of savvy innovators drawing on new ideas and technologies might already have whooshed through the station, leaving the company standing haplessly on its own crumbling platform. With Twitter seemingly caught in a corporate vortex of its own making, in which innovation is a thing of the past and power is what counts most, it’s reasonable to ask whether Twitter is worth saving at all.

The recent flap about Kanye West’s antisemitic comments, which began shortly before Musk assumed control of the company, underscore this point. Ye’s overlapping tirades all began with a tweet, in which the self-proclaimed genius-god informed us that, though presently sleepy, he would be going “deathcon 3 on Jewish people” in the morning. Cue the sound of 200 million tweeters gasping.

Twitter today is a far cry from a “micro-broadcasting platform” (as we once quaintly called it). It is the world’s most powerful engine of digital influence. And with rage erupting on every corner, vociferous arguments over what are essentially hobbies, and the endless lava flow of fake invective, it often feels like the online equivalent of an exciting and edgy city where you really don’t want be caught out after dark.

Accordingly, the moment the authorities turn up to impose order is precisely the moment everything seems to get worse. People are banned and suspended, the factuality of benign tweets is interrogated, coveted “blue checks” are withheld or awarded like Tammany spoils, and all of us shamelessly chase the street drug of choice, “engagement” — likes, retweets and comments (but only in their appropriate ratios) — that Twitter has so comprehensively conditioned us to crave.

The result is that most Twitter users feel as if they’re more struggling against, rather than empowered by, the platform. LibsofTikTok, an account with 1.4 million followers, has been suspended nine times in recent months, including in instances where no offending tweet was cited. Alex Berenson, the former New York Times reporter who has vocally expressed skepticism regarding the safety and effectiveness of Covid-19 mRNA vaccines, sued Twitter to get back onto the platform after a permanent ban, resulting in a settlement that saw his account reinstated.

“Suspensions strengthen my resolve to continue fighting,” Chaya Smith, owner of the LibsofTikTok account, tells me. “Every time I’m suspended I’m only empowered to continue fighting even harder. Suspensions just mean they’re scared.”

The latest firey debate unfolding on Twitter is about who gets — and doesn’t get — verification, the blue tick of social media status. Musk changed that by making verification part of the Twitter Blue subscription, which now costs $8 per month. But the flattening of the verification process has left many in the Twitter status hierarchy (you can guess which side of it) upset. “$20 to keep my blue check,” wrote Stephen King, referring to a previously proposed price for Twitter Blue. “Fuck that. They should pay me. If it gets instituted, I’m gone like Enron,” wrote King, whose net worth is estimated around half a billion dollars.

The verification issue points to a real problem, one tied into Twitter’s top-down, and seemingly politicized, decision making. Pre-Musk, many prominent users believed they were denied verification because they challenged the collection of virtue-signalling orthodoxies that have come to be known on the platform as “the current thing.”

Jay Bhattacharya, a professor of medicine at Stanford University and research associate at the National Bureau of Economics Research, has seen his verifications requested repeatedly denied.

“I’ve had charlatans impersonate me on the site many times, including people who were obviously using my name to scam people,” says Bhattacharya, who has 230,000 followers. “Twitter has eventually blocked them but it took too long. I would think being verified would protect against at least that.”

Both Smith and Bhattacharya feel an invisible hand behind the administrative actions, which they say points to clear bias.“I can’t help but notice that so many of the larger pro-lockdown accounts are verified, while many of the anti-lockdown accounts like Martin Kulldorff’s are not, and in some cases are censored,” says Bhattacharya, who vocally opposed blanket lockdowns in response to the pandemic. “The effect of these decisions is an editorial stance by Twitter in favor of lockdowns,” Bhattacharya says.

Days after Musk took control as CEO of the company, news broke that he intends to revamp the verification system by charging up to $8 a month for blue checks. But this almost seems like a Band-Aid on the bigger question of how much top-down control Twitter can, and should, exert.

This question — of whether Twitter is a platform, which doesn’t make editorial decisions, or a publisher, which very much does — is at the heart of years of debate concerning moderation, censorship and free speech on social media. A great deal of the motivation behind the publisher-platform debate stems from a piece of US law known as Section 230, which protects platforms from prosecution related to third-party content.

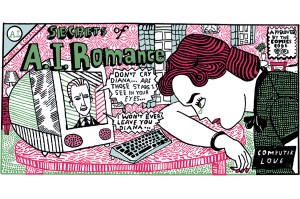

In reality, the publisher-platform dichotomy has done little more than bring us to an impasse, with platforms like Twitter arguing in court that they bear no responsibility for the content they carry, though they behave like nothing so much as publishers. But in an even more important sense, technology has dissolved the distinction between publisher and platform. Artificial-intelligence algorithms that distribute content on social media now serve as super-editors that make millions of editorial decisions per second as they elevate and suppress content based on projected engagement.

The rise of this HAL-like presence shepherding us toward what tweets to like is rooted in Twitter’s business model. “We live in a world right now where the whole business model is to decide which content to distribute for the purpose of driving engagement, for the purpose of driving ad revenue,” says Harvard law professor Lawrence Lessig, an authority on free speech, who compares the effect of this cycle on the body politic to that of fast food on the human body.

“Unfortunately for us as humans, the kind of content that drives up engagement is the most divisive, most polarizing, most hate-inducing, most poisonous content that you could serve,” says Lessig. “So if you turn on the AIs behind the Facebook news feed or the Twitter feeds and you say to them, ‘maximize engagement,’ they will feed us poisonous content.”

While it’s tempting to ascribe the poison cycle to corporate greed — companies trying to squeeze every last cent out of every last eyeball — the reality is that the problem is structural.

“If you look at companies like Twitter, generally there’s a broad problem of trying to have one company paying for the hosting,” says Al Morris, the founder and CEO of Koii, a web3 company that builds technologies for applications such as decentralized social media. “Every single user that joins means a little bit more computing resource is needed — and somebody’s gotta pay that bill. The result is that Twitter is no longer beholden to the users, but to the advertisers.”

This business model relies on aggressive approaches to selling advertising, which in turn depends on relentlessly driving user engagement at all costs — and has turned the “digital town square” (as Elon Musk generously describes Twitter) into something that Balaji Srinivasan, a leading thinker of the philosophy of decentralization, calls “the prison yard.”

Meanwhile, Twitter’s own research shows the company facing a downward trajectory. Reuters recently reported that an internal document damningly titled “Where did the Tweeters Go?” had found that the 10 percent of “heavy” Twitter users responsible for 90 percent of the site’s content are abandoning ship. In their place, the report says, is an army of bots and fake users producing crypto spam and porn.

For pioneers of web3 (the set of technologies born out of the blockchain revolution), the debate about the future of social media is cast not in terms of left or right, but of centralized and decentralized power. These innovators are beginning to translate advances from the crypto world into human and, in important ways, humane solutions. One of the biggest ideas on the horizon is also among the simplest: giving social media users the power to pick up their entire social graph (the collection of relationships, clout, content and interactions that makes up a profile) to seamlessly plug it in elsewhere. This is the kind of technological feat that web3 technologies seem uniquely suited to pull off.

The potential benefits to the user are enormous: imagine being able to participate in as many social networks as you have interests, without having to establish relationships, develop post histories or reputation or even create new logins each time you switch. If Twitter begins to feel a wee bit hellish, flipping to a small social network for homesteaders, endurance runners, mindfulness devotees or baking enthusiasts would be no more burdensome than opening a new tab on your browser.

While the advantage this offers individual users is clear, the collective benefit to society might be even greater. Bill Ottman, founder and CEO of decentralized social network Minds.com, notes that when people are deplatformed for hate speech or threats of violence by major sites like Twitter or Facebook, they don’t just cease to exist. “Deplatforming guarantees that deradicalization will never occur,” says Ottman, who works closely with Daryl Davis, the deradicalization expert who has convinced more than 200 KKK members to leave the Klan. Ottman and others in the field advocate the creation of a “self-sovereign identity,” or SSI, a digital identity wholly owned by the user.

Twitter’s co-founder and former CEO, Jack Dorsey, advocated just this approach in a series of text messages with Musk that were part of the discovery process in the lawsuit that arose when Musk initially backed out of the deal to buy the company. In one message, Dorsey told Musk that he believes the future of social media lies in an approach that, in many ways, is completely at odds with the advertising-centric, top-down company Twitter has become.

Dorsey wrote that a new incarnation of social media “must be an open-source protocol, funded by a foundation that doesn’t own the protocol, only advances it.” Notably, he added that “it can’t have an advertising model.”

This protocol-based model is being developed by networks like Farcaster, as well as Tel Aviv-based Secret Network. Dorsey is building his own version with something he calls Web5 by creating decentralized identifiers, or a version of Twitter’s blue-check verification that is both permanent and does not rely on any one company or group to bestow (or retract) it.

This approach is strikingly similar to one of our most entrenched and beloved digital technologies, email, which doesn’t depend on a central operator, but works according to a set of agreed-upon instructions that any email provider can implement (as Hillary Clinton’s DIY server illustrated so neatly).

Musk’s three-word response to Dorsey’s suggestion — “super interesting idea” — spoke volumes, but mostly for what it did not indicate: an affirmation that the Tesla CEO is intent on embracing a decentralized approach to Twitter’s myriad problems. The logic behind this omission is clear: Musk knows that a company cannot sabotage the business model that drives its revenue by handing the keys to the kingdom to… well, everyone.

“Transitioning Twitter into a web3 company by decentralizing your product and commercial models, you’re opening up the moat and market share to be cannibalized not just by the market, but by your own product,” says Mitchell Travers, who is co-founder of Soulbis, a blockchain firm.

Musk has publicly averred he did not buy Twitter to make more money but because “it is important to the future of civilization to have a common digital town square.” The problem is that this ideal may be at odds with Twitter’s overweening corporate imperatives, and more suited to other kinds of technologies.

As we discover “socialness” in many forms of media, from Twitch streams to massive multiplayer online games, our understanding of a social network, and of social media more broadly, is expanding and becoming fluid. It may be that this groundswell of social change being created in the digital sphere, not Twitter’s micromanagement, is what presents the greatest threat of extinction to the famous blue bird.

The upshot is that the zero-sum game of Twitter, where users score clout by humiliating and demeaning others (“dunking” or “owning”), might give way to something that more resembles a limitless game that prioritizes play, open interaction and, most of all, community.

“The difference I’m seeing for this next major stage of development,” says Joesph Beverley of Soulbis, is that we’re realizing we can have multiple forms of interaction that doesn’t at first glance seem like social media but in reality provides greater touch-points.”

More than technology, regulation or share prices, it’s that last idea, community, that might do to Twitter what Tesla’s lithium-ion batteries will eventually do to the combustion engine. If Twitter today resembles an echo chamber where users are constantly engaged in a shouting match, it’s because, before the company existed, there was nowhere else to go. Somehow, we all arrived there.

But meaningful options are forming. New technologies, like those being created in the realm of web3, are allowing new settlements on the infinite frontiers of the Internet. Communities of people with different values, languages and interests are being built, and in place of the fiercely centralized silo of Twitter something more like an endless array of tiny communities is rising — a million humble utopias instead of one highly stratified Hell.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2022 World edition.