For more than thirty years, Scott Adams has captured the absurdity and humor of office life in his popular syndicated newspaper cartoon strip “Dilbert.” The title character, an oblong-headed, cubicle-dwelling everyman, is one of the most familiar cartoon characters in America, but last September he vanished from more than seventy newspapers.

Shortly before Dilbert’s partial disappearance, his opinionated creator had set his sights on ESG. Adams’s views on the vogue for “Ethical, Social and Corporate Governance” investment strategies weren’t exactly difficult to discern. In one strip, for example, Dilbert asks, “What is this ‘ESG’ thing I keep hearing about?” His sidekick Dogbert offers a definition: “Imagine if a crooked politician and a crooked financial advisor got married and had a baby.” “So… ESG would be that baby?” “Only if it is colicky and has firehose diarrhea.”

While Adams didn’t attribute the newspapers’ decision to drop the cartoon to his stance on ESG, he did pledge to “destroy ESG… or at least take a shot at it” shortly after the move. He is not alone; the ranks of the forces taking on ESG have been growing lately. They include investors, lawyers, regulators, climate change activists, energy companies, state treasurers, state legislators, congressmen, senators, 2024 presidential contenders — and now a cartoonist.

The ESG story starts in 2004, when the three-letter acronym appeared in a UN report arguing for environmental, social and governance considerations to be hardwired into financial systems. Since then the term has been on a long but rapidly accelerating journey from NGO-world obscurity into the financial mainstream and subsequently the political limelight, prompting strong reactions from a chorus of prominent figures. Elon Musk calls it “a scam.” Peter Thiel says it’s a “hate factory.” Warren Buffett describes it as “asinine.”

Unsurprisingly for a piece of UN jargon that has become part of the political cut and thrust, “ESG” is often used to mean different things. Properly defined, it refers to an investment strategy that factors in environmental, social and corporate governance considerations. That might mean not investing in oil and gas companies, for example. Or it might mean only investing in companies that have a stated commitment to diversity, equity and inclusion. As it has grown in infamy, the acronym has also come to refer not only to investment products billed as ESG, but to other practices through which investment firms use their customers’ money to push political ends. For example, your pension may not be invested in an ESG fund, but the manager of that money may still be using stocks owned on your behalf to pursue political goals. A third, even broader, meaning is as a synonym for woke capitalism: a broad catch-all for big business’s embrace of bien pensant opinion, particularly on the environment.

Some of ESG’s biggest proponents have embraced a similarly broad-brush frame. Thanks to his remorseless embrace of right-on buzzwords and jargon like “stakeholder capitalism,” Larry Fink is the financial titan most associated with ESG. As CEO of BlackRock, the world’s largest asset manager, Fink never misses an opportunity to point out the happy coincidence that investing with his firm will not only make you rich, but save the world. “We focus on sustainability not because we’re environmentalists, but because we are capitalists and fiduciaries to our clients,” wrote Fink with characteristic slickness in his 2022 annual letter last January.

This win-win rhetoric has been the rallying cry of the ESG crowd on what has looked like an unstoppable march. Make money and do good: who could possibly object? Millions have bought into this seductive logic. Globally, more than $35 trillion of assets are invested according to ESG considerations, an increase of more than 50 percent since 2016. From 2020 to 2022, the size of ESG assets in the United States grew by 40 percent. According to an analysis by the asset manager Pimco, ESG was mentioned on just 1 percent of earnings calls between 2005 and 2018. By 2021, that figure had risen to 20 percent.

ESG first came across Riley Moore’s desk soon after he was sworn in as the state treasurer of West Virginia in January 2021. As he explains, energy companies operating in the coal- and gas-rich Mountain State complained to him of the difficulties they were having accessing capital thanks to the big banks’ ESG lending policies.

Forty-two-year-old Moore is a careful, deliberate speaker with neat, close-trimmed hair and tidy features. “As we started to peel back more layers of the onion,” he tells me, “we discovered how insidious and pervasive this is throughout the financial sector in the United States. It’s in our pension funds, our rating agencies, the financial institutions of the country. It touches on all of it.”

Access to capital is a very real problem for energy firms these days. According to Goldman Sachs, the cost of capital is 15 percentage points higher in high-carbon versus low-carbon energy products today. The bank also estimates that “sectors like shipping, oil and gas, cement, steel, are all investing 40 percent less of their cash flow than they have done in their long-term history.”

It occurred to Moore that US states are big customers of the same financial institutions that the businesses which provide high-paying blue-collar jobs in West Virginia were struggling to borrow from. Why should we do business with firms that seem determined to hobble our state’s economy, Moore wondered — first to himself, then anyone who would listen.

“We looked at all the banks and asset managers my office was doing business with, and a good number of them had prohibitive lending policies to the fossil fuel industry,” he explains. Moore’s response did not rely on the passage of onerous regulation. It simply involved the state of West Virginia exercising its right to do business with whomever it chooses. Last January, Moore responded to BlackRock’s call for companies to embrace net zero by dropping the asset manager’s funds from West Virginia’s investment portfolio. The numbers involved were small — but the symbolic act suggested more action would soon follow. Sure enough, in August, West Virginia deemed five financial institutions — BlackRock, Goldman Sachs, JPMorgan Chase, Morgan Stanley and Wells Fargo — ineligible for state banking contracts. “I simply cannot stand by and allow financial institutions working against West Virginia’s critical industries to profit off the very funds their policies attempt to diminish,” said Moore when he announced the move.

Moore claims such moves are working, pointing to US Bank, which, as he explains “actually changed their prohibition on lending to thermal coal and pipeline construction for natural gas and oil” to avoid ending up on the list.

Other states have followed West Virginia’s lead. In October, Louisiana pulled nearly $800 million of funds out of BlackRock. Missouri and South Carolina have done the same. In total, at least a dozen Republican state treasurers have been involved in a pushback against ESG in some form. In a sign of ESG’s growing political salience, Moore has announced a run for Congress and framed the move as a chance to take the fight against ESG to Washington.

While treasurers are flexing their state’s financial muscles, attorneys general have been using their legal authority to push back. In August, nineteen state attorneys general wrote to Larry Fink, warning that BlackRock “appears to use the hard-earned money of our states’ citizens to circumvent the best possible return on investment, as well as their vote.” The charge is that by factoring in anything other than maximizing return on investment, money managers are in breach of the “sole interest rule,” which requires investment fiduciaries (i.e., money managers) to maximize financial returns. Others go further, claiming not only that asset managers have breached their fiduciary duty to their customers, but that trustees who sit on public pension boards that invest with those firms have also violated their fiduciary duty.

The next step will be for states to strengthen their fiduciary rules. The American Legislative Exchange Council, a conservative nonprofit that helps draft legislation for state governments, has devised a bill that does exactly that.

Vivek Ramaswamy calls the use of customers’ money to advance political objects rather than their best financial interests a “cut and dried fiduciary breach” and one that he thinks is happening on a large enough scale that “it might be the largest fraud of the twenty-first century.”

A biotech entrepreneur turned anti-woke crusader, Ramaswamy is the author of Woke, Inc.: Inside Corporate America’s Social Justice Scam. He sees the rise of ESG as an opportunity as well as a threat. That opportunity is two-fold, he thinks. First: if investment decisions are increasingly being made based on factors other than maximizing returns, then politically unpalatable stocks should, logically, be undervalued. Second: if more and more large asset managers are putting ESG considerations ahead of maximizing their customers’ returns, there is an opening for firms with a ruthless focus on the bottom line to scoop up disgruntled customers.

Last year, with the backing of billionaire venture capitalist Peter Thiel and activist investor Bill Ackman, Ramaswamy founded Strive Asset Management. Ramaswamy says the firm is focused on nothing except maximizing returns. “Long-run value creation should be the sole objective, period,” he says, and Strive’s promotional material claims that the firm puts “excellence over politics.”

Among the products Strive offers is an exchange-traded fund focused on US energy stocks with the unambiguous ticker DRLL. Another, focused on the US semiconductor sector, goes by SHOC. “I think that capital owners are waking up to the fact that it’s their money, not the money of the institution that invests on their behalf. And that their own desires actually matter,” says Ramaswamy.

If the anti-ESG movement has the wind in its sails, that’s in large part thanks to last year’s tumultuous geopolitical events and economic trends, foremost among them the war in Ukraine. The Russian invasion has transformed the ESG debate in two ways.

First, it has underscored the ethical dilemmas ESG champions would rather ignore. For example, many ESG funds rule out investment in weapons manufacturers. Is it really ethical to deny capital to the firms producing the material Ukraine needs to survive? Indeed, the socially responsible position is arguably the exact opposite.

Second, it has transformed the energy conversation in a way that has made many more of us acutely aware of the importance of cheap, abundant and reliable energy — and conscious that it cannot be taken for granted. In other words, each of us is a little more like Riley Moore’s West Virginia constituents, who don’t have much time for net-zero grandstanding given that they will be the ones who pay a heavy price for someone else’s pursuit of feel-good goals. What has always been true is becoming clearer: a financial system that starves domestic energy producers of capital not only hurts those whose savings are being used to pursue political ends, but ends up as a de facto tax on US consumers in the form of higher energy costs. ESG, says Goldman Sachs’s Michele Della Vigna, “creates affordability problems which could generate political backlash. That is the risk — political instability and the consumer effectively suffering from this cost inflation.”

Add to that rising prices, a bleak economic outlook and a punishing bear market, and the rosy no-trade-off rhetoric of the ESG crowd looks more like empty salesmanship than ever. There is a logical fallacy at the heart of ESG thinking — if its priorities really are such a no-brainer for any investor keen to maximize long-term value, then why the need for ESG restrictions at all? That fallacy is a lot easier to spot when the going gets tough.

While most of the anti-ESG energy comes from the right, a left-wing critique is also gaining traction. Environmental campaigners are starting to realize that, faced with a choice between profitability and saving the world, large financial firms aren’t likely to stay on their side for long.

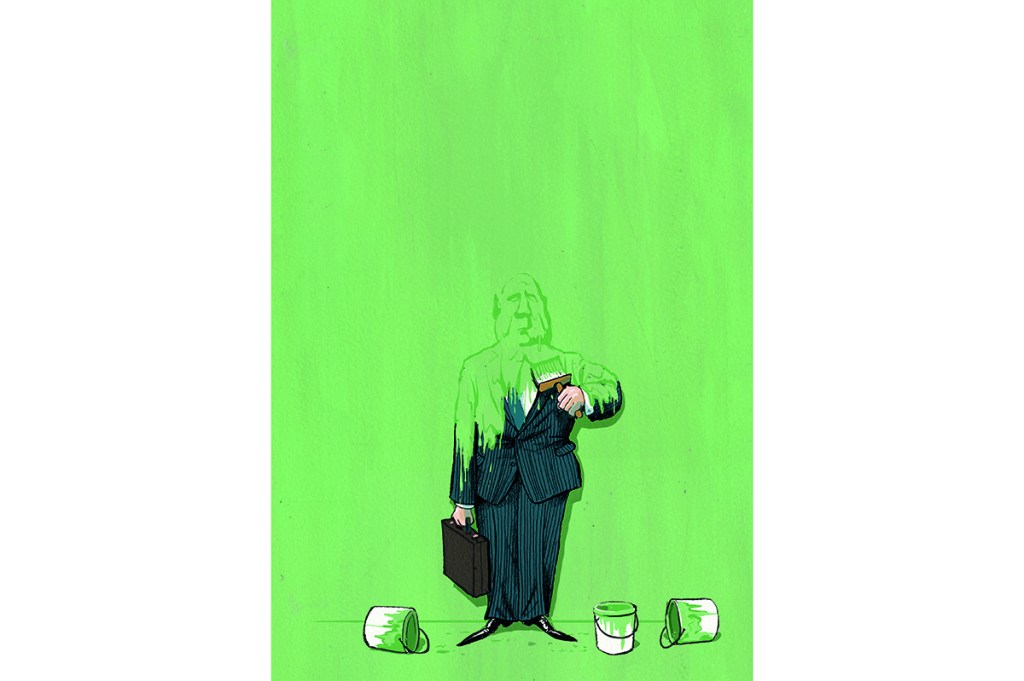

Meanwhile, regulators are paying closer attention to some of the bolder claims made by ESG’s champions. Last year, the asset manager DWS was raided by German police as part of an investigation into allegedly misleading claims made about ESG investments. Here in the United States, the Securities and Exchange Commission has launched a taskforce to clamp down on this so-called “greenwashing.”

Republican politicians, regulators, climate-change activists and upstart rivals: ESG’s defenders have a growing list of opponents. And yet the juggernaut rumbles on. The growth of ESG assets may have slowed, but that it is growing at all in such an unfavorable environment demonstrates its considerable durability. It is helped by the renewable lobby and an administration that is weighing mandatory climate and sustainability disclosures for publicly traded companies.

But it is also simply a question of demand. In November, a Stanford survey demonstrated a large generational gap in investing preferences. The average twenty- or thirty-something said they were willing to lose between 6 and 10 percent of their investments if companies improved their environmental practices, while “the average baby boomer was unwilling to lose anything.”

For many of ESG’s critics, though, there isn’t necessarily anything wrong with sustainable investing — as long as customers aren’t being misled and Americans aren’t unwittingly having their savings deployed to satisfy their asset manager’s political objectives. “The pro- or anti-ESG tug of war is one thing,” says Ramaswamy. “What matters is that we restore integrity to the system. The problem isn’t ESG per se. It’s that you have the large-scale misuse of other people’s money.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.