There’s always been a market for nostalgia. Keats, the huckster of Greek glories, put it best: “Heard melodies are sweet, but those unheard are sweeter.” But the peculiar achievement of Lester Bangs, the cantankerous rock critic played by Philip Seymour Hoffman in the film Almost Famous (2000), is to sell us some self-confessedly unsweet music.

True rock and roll, the Bangs character tells us, is “gloriously and righteously dumb” and could suffer no worse fate than to become an “industry of cool.” Of course, by his lights, the golden age has passed; all that remains is “the death rattle, the last gasp, the last grope.” If nostalgia is a drug, he has mainlined the stuff. What are you on, man, and where can I get some?

At least that is the question posed by the innocent fifteen-year-old William Miller, an aspiring critic who buttonholes Lester for advice at the beginning of the musical version of Almost Famous. William is a stand-in for the original film’s director Cameron Crowe, who began scribbling for the real-life Bangs’s Creem magazine in high school, and in short order was writing cover stories for Rolling Stone.

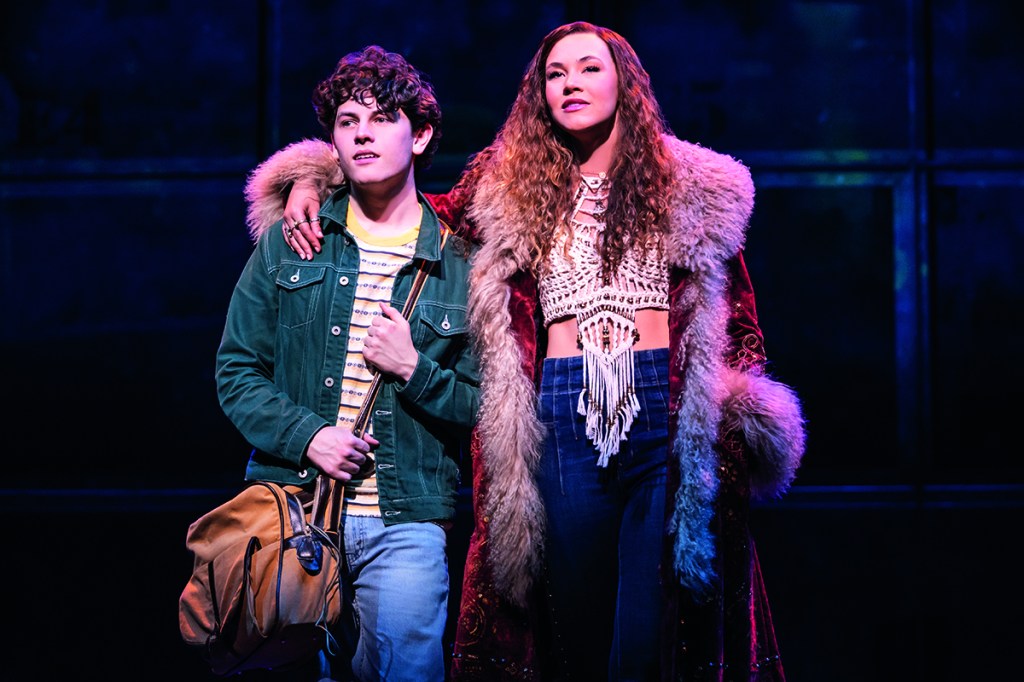

Crowe loosely based the film on his experience of being on the road with the Allman Brothers, crafting his first cover story. He embellished his account on the big screen in a love triangle plot comprised of star Stillwater guitarist Russell Hammond (played by Chris Wood on the stage), illustrious groupie Penny Lane (Solea Pfeiffer) and, of course, the scrawny teenage William (Casey Likes).

In this new musical version, Lester Bangs (Rob Colletti) often plays a sort of tutelary spirit, smiling approvingly or offering advice from the wings while William mucks about with roadies and drifters; in the words of his mother Elaine (Anika Larsen), those “poet[s] of drugs and promiscuous sex.”

Is it fair, realistic or at all believable to cast this Lester Bangs as a guardian angel? In evidence, a sampling of his real-life pronouncements in Creem: “Lou Reed is a completely depraved pervert and pathetic death dwarf and everything else you want to think he is.” Also, “Lou Reed is my hero.” Bob Dylan’s Blood on the Tracks is “at worst an instrument of self-abuse, at best innocuous as a crying towel.” Of Paul McCartney & Wings: “Having Linda [McCartney] play keyboards onstage in a multimillion-dollar tour is like hiring a good black construction worker to edit the New York Times. And then not even giving him a chance to fuck up, just a desk instead.”

Bangs did have a gentler side. “Black Sabbath are moralists,” he once argued. “The ultimate thrust of what Black Sabbath is saying or trying to say is an uncommonly humanist impulse.” They’re “probably the first truly Catholic rock group.” Alice Cooper also made him giddy: “You can bet your chrome-plated Led Zeppelin dildo he’s wholesome.”

The more profound lesson is not whether Bangs was warm-hearted; in propria persona he was never really a great candidate for Broadway or Hollywood. But realism isn’t the point. The Lester Bangs of Almost Famous only needs to be an emblem of rock and roll wistfulness. In the movie, he is backed up by a lush soundtrack spanning Rod Stewart, the Beach Boys, the Seeds and Clarence Carter. The music supports such mythologizing: it’s the key in which the theme of nostalgia is played.

You’d think these musical elements would translate well to the stage, but composer and lyricist Tom Kitt has failed decisively in this task. The original numbers are bog-standard tunes dressed in twaddle. (“Why be stuck when there’s motion / Gotta move before it’s too late / So fly yourself ‘cross the ocean / And turn your good into great,” etc.) Classic rock songs, some featured in the original film, have been sprinkled in — “Ramble On,” “Simple Man,” “Tiny Dancer” — but it all sinks pretty quickly into the same gormlessly Broadway idiom that exists somewhere between jukebox musical and musical indifference.

The bigger problem is that the original Almost Famous is not about rock and roll so much as the people who loved it, bled for it and had to see it off. Growing up is an exercise in managing nostalgia, and it’s by means of rock music and the general nostalgia it evokes that we’re involved in the private longings of William, Penny, Russell and the rest. On film, music can sit atop the drama; on stage, it wrestles with it for space. The carefully sculpted plot has to be whittled away until the characters all turn into stick figures, dancing in a reprise parade.

The movie conjures up a moment — half-fact and half-fiction, but all bustling and alive. The musical just made me miss the movie.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2023 World edition.