Paul Johnson, the author, journalist and historian, has died at the age of ninety-four. He wrote more than forty books, edited the New Statesman from 1965 to 1970, and wrote a column for The Spectator from 1981 to 2009. Below are some extracts from his Spectator columns, all of which are available on our archive.

On the twentieth century

“Only six weeks to go before the end of the century: time to draw up a list of its political success stories. My criterion is the simple utilitarian one of Jeremy Bentham: who did most to promote the greatest possible happiness of the largest possible number? Top of my list, then, is Lee Kuan Yew, who took over Singapore when it was pretty demoralized and its per capita income less than $100, and transformed it into one of the richest, safest, most orderly and sensible countries in the world. The media did not like him. Good. He in turn did not like bead-jangling, hirsute, pot-smoking, guitar-strumming hippies, and all the false philosophies which go with that kind of thing. He kept them out. That is one reason Singapore is virtually crime-free and a little paradise of old-fashioned virtues. Countless millions of hard-working Asians would love to live there, but the place is too small. It has no natural resources either. Lee’s achievement underlines the truth that the key to political success is the creative management of brain-power.”

Here is my list of the century’s greatest political figures, November 13, 1999

On Vladimir Putin

“I feel an intense antipathy for Vladimir Putin. No one on the international scene has aroused in me such dislike since Stalin died. Though not a mass killer on the Stalin scale, he has the same indifference to human life. There is a Stalinist streak of gangsterism too: his ‘loyalists’ wear masks as well as carry guns. Putin also resembles Hitler in his use of belligerent minorities to spread his power. Am I becoming paranoid about Putin? I hope not.”

Boris would make a great PM — but he must strike now, May 10, 2014

On moral relativism

“As I see it, the Satan who confronted Jesus during this encounter is the personification of moral relativism, and the materialism which creates it. What we are shown is not merely ‘all the kingdoms of the world’ but the entire universe, in all its colossal extent, reaching backwards and forwards into infinity and beyond the powers of the human mind to grasp except in mathematical equations. We are told: this came into existence, not by an act of creation, but as a result of the laws of physics, which have no moral purpose whatever — or indeed any purpose. There is no conceivable room for God in this process, and mankind is an infinitely minute spectator of this futile process about which he can do nothing, being of no more significance than a speck of dust or a fragment of rock. If you will accept this view of our fate, then there is just a chance that by applying the laws of science to the exclusion of any other considerations, and by dismissing the notion of God, or the spirit, or goodness, or any other absolute notion of truth and right and wrong, we shall be able marginally to improve the human condition during the minute portion of time our race occupies our doomed planet.”

What the temptations on the high mountain mean today, February 25, 2009

On writing

“Being a professional writer is a hard life. Producing a book, especially a long one, is a severe test of courage and endurance. For even after a successful day of writing, one must begin again the next morning, the blank sheet of paper in front of you: a daunting image to start the day, the mind empty, the brain groaning. I know. I have been at it for the best part of six long decades, and the number of books I have written is creeping up to fifty. Several are over 1,000 printed pages. Think of the agony!”

Short works of genius cheer up the writing profession, February 14, 2009

On Steven Pinker

“Two things struck me about Pinker. The first was his hair. It is beautifully bushy and curly, and its ‘sweet disorder’ is evidently the product of much trouble and art, and dollars. That tells me a lot about how his mind works anyway. The second thing was his extraordinary ineptitude in managing his visual aids. They were quite unnecessary anyway, adding nothing to his discourse. With one marginal exception, they merely repeated what he was saying in tiny, type-written characters illegible to most of his audience. But in order to put them on the screen he had constantly to dart backwards and forwards, an intensely irritating and distracting performance and of no help to the continuity of his unscripted talk. Unlike his hunter-gatherer ancestors, he is no great shakes at solving perfectly simple physical difficulties — or realizing that he does not need to solve them at all, that they do not in fact exist — and I suppose that too tells us a lot about how his mind works… Wonder is my response to the arcane mysteries about which the Pinkers are so sure. I agree with J.B.S. Haldane, a scientist too great to be a fundamentalist, who said that his chief impression, at the end of a lifetime of research, was of ‘the inexhaustible oddity of nature.’ To me God will always be the Great Eccentric.”

An entertaining evening finding out how Professor Pinker’s mind works, January 31, 1998

On castle life

“I do like to stay in a castle. Nothing grand. I have no desire to put up at Balmoral or Inverary. Blair Atholl or Castle Howard. with footmen striding, chambermaids tripping down the corridors, port-sipping and gunroom chatter after the ladies retire from the mahogany, and a general air of uneasy Edwardianism. But I do like to be surrounded by ancient stones, once capable of defying the crossbow and mangonel, even cannonades. I relish arrow-slits, the grooves in which drawbridges once slid, massive oak and iron-studded doors, even if now creakily opened by electric eyes; strange glimpses of dungeons from bathroom windows, the faint but unmistakable whiff of mediaeval fear, as ravens croak a fatal entrance under the battlements. And not only croaking birds but ‘the temple-haunting martlet.’ As Banquo puts it, ‘no jutty, frieze, buttress, nor coign of vantage, but this bird hath made his pendent bed and procreant cradle.’”

The castle of snoring owls and laughing ospreys, September 28, 2002

On newspapers

“A serious quality newspaper, which aims to make a contribution to the good government of our country, as opposed merely to selling copies and making money, ought at all times, but particularly during periods of crisis, to try and see government from the inside. In a parliamentary democracy like ours, all governments, whether left or right, are trying to serve the public interest according to their lights, often in the face of difficulties which it is not really in their power to control. Equally, prime ministers are usually doing no more than seeking, sometimes a bit desperately, to keep the coach on the road. They should be judged in that spirit.”

When an editor’s standards slip, November 18, 1989

On genetic engineering

“It was predictable that a new deity would soon take Marx’s place among academics, and now it has happened. Unlike Marx, Darwin was a genuine scientist, who, on a famous occasion, politely but firmly refused Marx’s invitation to strike a Faustian bargain. Darwin was modest in his claims, and most reluctant to have his work used for ideological purposes. But it always has been: first by the anti-religious campaigner T.H. Huxley, then by the social Darwinists, then by both the Nazis and the Stalinists, and now — more directly — by the scientific triumphalists. In the last half-century, biology has taken over from physics as the fashionable science on the campus and in the media, and that inevitably has led Darwin to displace Newton and Einstein in the egghead pantheon. Moreover, biology now has its own technology, which is expanding and proliferating at breathtaking speed, emitting intoxicating fumes which provide the new opium of the intelligentsia. This new technology is increasingly financed not, as was physics, by governments looking to the distant future, but by ordinary, anxious people looking for better bodies and longer lives and healthier children in the immediate present. Here is a religion which can make the sick well and the lame and the halt walk and — who knows? — raise Lazarus from the dead.”

Shaping up for a new moral catastrophe in the twenty-first century, October 17, 1998

On knowledge

“My heart goes out to the young just enjoying their first term at university. I remember well, in October 1946, the excitement of moving into college rooms at Oxford. The quest for knowledge seemed to me then the noblest of human activities, and still does so in a sense. (In the sense that, without it, humanity would perish ignominiously.) But I am under no illusions that knowledge brings satisfaction; merely hunger for more, and despair at ever being what Francis Bacon called ‘a full man’. I had a good education, and some remarkable teachers: and I have been educating myself ever since by writing books. But at the end of it all, and my seventy-fourth birthday imminent, I find that I have merely been exploring the limits of my own ignorance. I agree with Dr Johnson: ‘There is nothing so insignificant that I would rather know it than not know it’ and I have always proceeded by that rule. But what I do not know stretches to infinity. And I am no nearer knowing the answer to the question which matters most — perhaps the only question that matters at all: is there, or is there not, a God?”

When Wittgenstein picked up not the poker but the crucifix, November 2, 2002

On faces

“What fills me with delight and wonder are those instances, happily not uncommon, where fine feelings and unselfishness create a kind of facial beauty. It is said of a woman,‘’Oh, she has lost her looks’’ But some women find their looks. As they age, the goodness which is within them begins to display an external expression, to dominate the lines and contours, fill the cheeks with a soft radiance, illuminate the eyes and smooth all the wrinkles from the brow. We all know cases like this — men as well as women — where the simplicity and purity and benevolence of the soul begin to shine through the face, and to look at it is to peer into the essence of a noble spirit. That is the kind of portrait I would like to have painted.”

Orwell’s last words: ‘At fifty, everyone has the face he deserves’, November 4, 2000

On Pope John Paul II

“He has called our prevailing mode in the world ‘the culture of Death.’ Everywhere we look, vast weapons of destruction are being acquired, and others used. Entire states and religious movements are being organized to kill not in self-defense or of sheer necessity but as a way of life. Euthanasia makes steady strides. To all these, the Pope, in his childlike wisdom and holy innocence, in his boundless confidence in the goodness of almighty God and the ultimate triumph of the Spirit, upholds the culture of Life. They say he is a dying man, but I have a feeling he will be teaching us the Way, the Truth and the Life for some time yet.”

An old man of eighty-three versus an evil world, 22 November 2003

On England

“One reason why the Angles, Saxons and kites made a success of their English ventures is that they cut their links with their Continental homelands and identified themselves completely with the new country they created, evolving a distinctive language. King Alfred and the other extremist kings framed their laws in it rather than in Continental Latin. Their Norman and Angevin successors were never able to impose their vernacular tongue, French, on the bulk of the English, and eventually, in the fourteenth century, French was flung off even as a courtly language. The Statute of Pleadings made it unlawful for cases to be tried except in English. At about the same time the great Crecy window was built in Gloucester Abbey to celebrate a notable victory of English over Continental arms, to mark the maturing of the first truly English architectural style, Perpendicular, and to complete the bifurcation of the English and French cultures. If all these characteristic actions of us islanders, over many generations, were extreme, then indeed extremism is the English norm.”

This blessed plot, this realm, this nation of extremists, this England, October 23, 1999

On male vanity

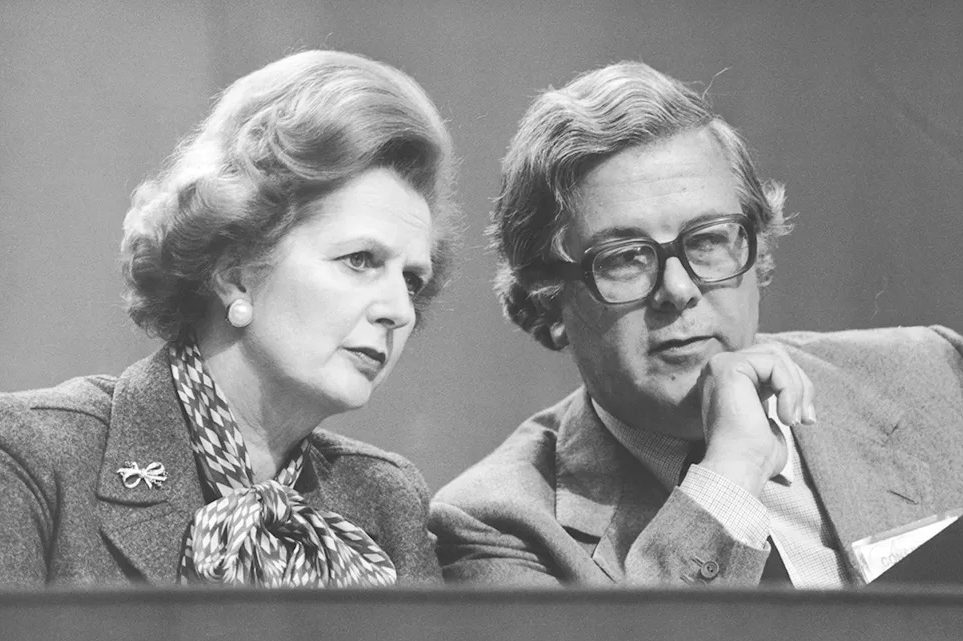

“My experience is that women are less vain than men. A certain vanity is part of their job of being a woman, of achieving the routine self-presentation that is expected. Mrs. Thatcher scored high marks there, though no one would call her vain. On the contrary, politicians such as Shirley Williams, Mo Mowlam and Clare Short are rightly criticized for not being vain enough. If you see a woman looking at herself in a shop window, you take no notice. On the other hand, if, as I once did, you followed a certain tall and leonine Tory along a Brighton street during a party conference and counted the times he scrutinized himself in a convenient sheet of glass, you realize why the ancient Greeks pinned the legend of Narcissus on a male. Women are not so much vain as make vanity work for them. Queen Elizabeth I, often cited as the epitome of visual vanity, in fact arrayed herself in paint and finery for political and regal purposes. Being a woman, she had to rule by art not strength, by charm not fear, and when left to herself and not on parade (particularly as she aged) she often wore a humble black gown for days together.’

Vanity is a man’s fault but a woman’s profession, February 2, 2002

On America

“What is America? It is not a race but a cohesion of all the races of the world. It will soon be a nation of 300 million, 10 percent of whom were not even born there. Its creation from Europe. Africa and Asia is a continuing process, as countless immigrants arrive each year and are quietly absorbed and prosper. Moreover, these citizens, whose parents, grandparents or ancestors came from all over the world, are given the chance to participate in democracy at all levels, which exists nowhere else on earth. More than 600,000 offices in the US are elected. The entire public ethos of America is fashioned to finding out what the voters want and constructing policy on their wishes. America is successful precisely because it is a working multiracial democracy. To be anti-American, therefore, is to be anti-humanity. For no other country represents so clearly the current wishes and long-term aspirations of the human race.”

To hate America is to hate humanity, April 6, 2002

On political correctness

“Today the ideological diseases which rot free minds come from the United States, above all from its campuses, its media and its immensely powerful political pressure groups. America has always been a country where extremism of all kind flourishes. Political Correctness and compulsory moral anarchy are modern manifestations of the same propensity which hanged unfortunate old women at Salem in the 1690s, made the Civil War possible, detonated the Red Scare in 1919 and McCarthyism in the late 1940s. America always subdues these extremisms in the end, but the battle is often hard-fought and bloody.”

Off for a spot of dragon-hunting in the land of Political Correctness, October 1, 1994

On prayer

“Silence — that most precious commodity in our world of noisy doing and building, of raucous getting and spending. Most of my life I have begun the day, usually about 7 a.m., with a visit to church, silent and empty at that time. Alas, shortage of priests now makes it difficult. Most churches are locked until 10 o’clock on a weekday, and that is too late for me. Still, occasionally I like to visit a church later in the day, if I can find one open. I almost invariably experience that huge silence, almost palpable, in such tremendous contrast to the hubbub outside. I only stay a minute or two. But it is nourishing and reassuring. I fill my lungs, and emerge restored. My faith is a very physical thing. But it is everything else, too.”

Reason to believe, December 15, 2012

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.