Kyiv

General Valeriy Zaluzhny, stocky, forceful, apple-cheeked, sits at the desk in Kyiv from which he commands all Ukraine’s armed forces. I ask him what they need from the West. First, air defense. With a twinkle in his eye, he unzips his khaki fleece to reveal a garish T-shirt demanding “F-16s!” Next on his list are long-range missiles such as the American ATACMS and the Franco-British Storm Shadow, so they can hit Russian targets beyond the range of their current armory. Now the general jumps up, disappears behind a glass-fronted office cupboard into an improvised sleeping area, and returns with another T-shirt, this time calling for missiles. It seems he has a T-shirt for every weapon system.

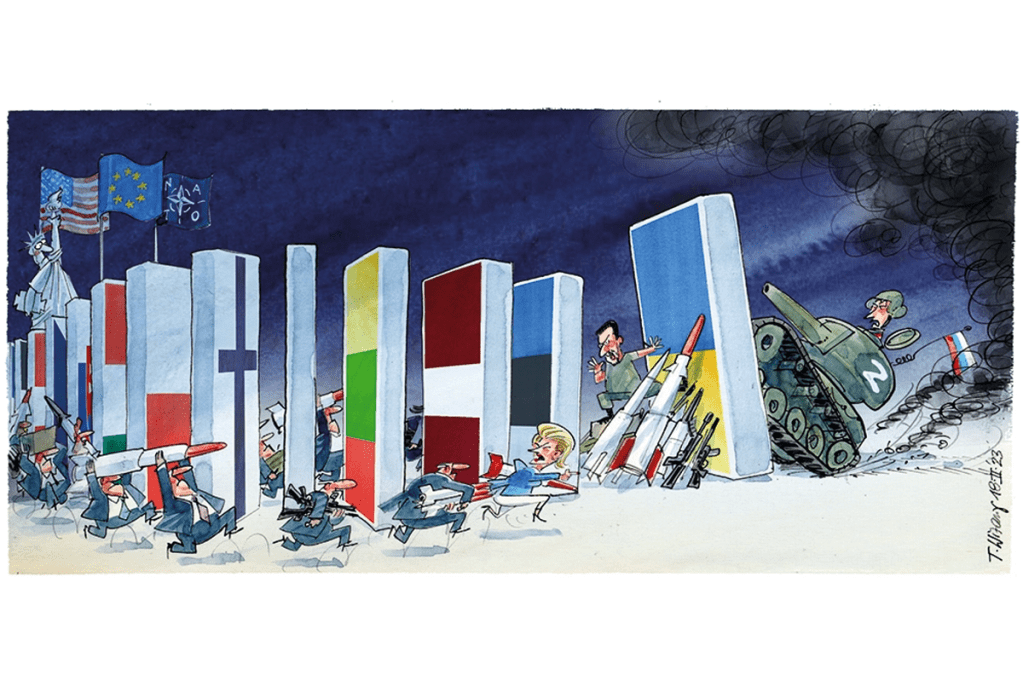

Approaching the first anniversary of Vladimir Putin’s full-scale invasion, the Ukrainian forces are running dangerously low on the gauges of ammunition needed for their still mainly post-Soviet weaponry, as Russia sends wave after wave of criminal cannon fodder against towns like Bakhmut. The Ukrainians don’t yet have anything like enough of the NATO-standard kit to replace the older gear: 152mm caliber for post-Soviet guns, 155mm for NATO ones — on that difference of three millimeters the future of Europe may hinge.

There’s a similar issue with tanks. Although some German-made Leopards and British Challengers are at last coming through, most of Ukraine’s tanks are still post-Soviet models. Without ammunition, Zaluzhny tells me, these would be “not tanks but tractors.”

Talking to the Ukrainian commander-in-chief, who is every inch the soldier’s soldier, you understand that the impassioned requests for more weaponry made by President Volodymyr Zelensky on his lightning tour of London (“wings for freedom”), Paris and Brussels are not simply a kind of rhetorical bidding contest. They reflect hard, precise military necessities. And a week spent in and around Kyiv, followed by some days at the Munich Security Conference, makes it clear that the next six months could be make-or-break time for Ukraine.

I arrived in Kyiv on a rattling old overnight train from Poland, straight into an air-raid warning and hence to several hours in a bomb shelter. But apart from time spent underground because of air-raid warnings (“We don’t have enough bomb shelters for our students,” one academic sighed, putting the problems of western universities into some perspective); apart from the power cuts, sandbags, ubiquitous soldiers and absent wives and children, life in Kyiv seems outwardly remarkably normal.

Everyone is mobilized for victory. My student assistant shows me the “Army of Drones” app on which you can also report the location of Russian troops. The head of Ukrainian railways tells me how they have kept the trains running, evacuating 4 million people and bringing in diesel for the whole country. Journalists, writers and artists document the genocidal character of Russian occupation. “This will be the best-documented war in history,” they say. In Bucha, Irpin, Hostomel and Borodyanka — names familiar on our lips as once were Srebrenica and Vukovar — there are scenes of destruction, first-hand testimonies and photos of atrocities that leave you feeling physically sick. In government offices and think tanks, people prepare at pace for reconstruction, reform and membership in both the EU and NATO. “Our card is our speed,” says Olha Stefanishyna, deputy prime minister for Euro-Atlantic integration.

In the Syayvo (“Radiance”) bookshop in central Kyiv, the staff collect Russian-language books to be recycled, with the proceeds going to the Ukrainian army. Shop assistant Lydia tells me they’ve already recycled more than 111,000 books and bought a military support vehicle which grateful soldiers call the Syayvomobile. In the cellar, she shows me a pile of neatly bundled books, including Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov and a Russian edition of Kafka, waiting to be pulped. A man wanders in with a couple of new bundles and asks diffidently: “Could you take fifty-five volumes of Lenin?” Of course! When this bloody war is over, Lydia and her colleagues would like to make their bookshop more modern and “European-like.” (I have posted photos from many of these locations on my “History of the Present” Substack newsletter.)

Yet there’s also exhaustion, sober realism and consciousness of a relentlessly growing human cost. “In a way we are losing,” one anti-corruption activist says, “because our people are dying.” I think of Yevhen Hulevych, an editor and literary critic turned frontline soldier whom I met when he was recovering from his wounds in December in Lviv. He was killed in action a few weeks later, apparently near Bakhmut.

A crucial question in any war is “Whose side is time on?” By 1942, for example, time was clearly on the side of the anti-Hitler allies. But in this war, time may be on the side of Vladimir Putin. There’s a strong suspicion that Putin thinks so too. If China were to send weapons, that would further strengthen his hand.

Hence the constant Ukrainian emphasis on speed and urgency. At the Munich Security Conference, the German chancellor Olaf Scholz praised his own caution, saying “Sorgfalt vor Schnellschuss” (roughly, care rather than overhasty action). A fine motto for peacetime, but in war, the slowness works for Putin. So we in the West must start matching Ukrainian speed. We need to get more ammunition and weapons faster to the places General Zaluzhny needs them, and increase financial support to sustain the faltering Ukrainian healthcare system, schools, housing and overall budget. The existing weapon and ammunition stocks of western armies are significantly depleted, so much did we lower our guard during what I call the post-Wall period (i.e. after the fall of the Berlin Wall on November 9, 1989), which ended on February 24, 2022. But in Munich, I heard representatives of the European defense industry say they could quickly ramp up production if political leaders would cut the red tape and national protectionism that still besets this sector.

Yet the West also needs to be clear how these weapons may be used. The key question here is Crimea. At the moment, the Russians, grinding forward in the Donbas, have the strategic initiative, but the Ukrainians are preparing a major counteroffensive this spring, using some new brigades equipped and trained by the West. It’s no secret that one of the options would be to push south from the neighbourhood of Zaporizhzia, towards the Sea of Azov. If successful, that could bring them to the edges of Crimea.

Almost every Ukrainian I have met says they should retake Crimea. Their arguments are moral (“Too many have died,” Yevhen told me in Lviv, for this not to happen). Legal (this is Ukrainian sovereign territory). Political (polling suggests Ukrainian public opinion would not forgive any Ukrainian politician who gave up on Crimea). Cultural (“To give up on Crimea is to give up on the Crimean Tatars,” I was told by Tamila Tasheva, head of an office for Crimean affairs that President Zelensky has placed at the heart of Kyiv’s government quarter). But they are also strategic, both long and short term.

Long term, they say that Ukraine could never enjoy security with Russian forces squatting in Crimea. Short term, Ukrainians argue that Crimea is the one thing that most Russians really care about, much more than the Donbas, so that only by threatening to move into the peninsula, while using those long-range missiles to take down the Kerch Bridge, its vital supply link to Russia, can they force Moscow into serious talks.

A particularly vivid version of this argument was made to me by the head of Ukrainian military intelligence, Kyrylo Budanov, sitting in his darkened office, with sandbagged windows and lurid oil paintings on the wall, while he demonstrated the campaign geography on a Google Earth Pro map on a giant screen. But several senior retired US generals, including Wesley Clark, endorse a more measured version of this case, and it does have a strategic logic. This is how you turn the tide of the war, forcing Putin to the negotiating table.

It’s also a big risk. Most policy-makers in the West, while they publicly parrot “territorial integrity” and “it’s up to the Ukrainians to decide,” privately think Ukraine should stop at Crimea. Their analytical starting point is the same one that makes Ukrainians want to go for it: Crimea is what really matters to Russia. So they fear Putin might escalate in response, perhaps even to the use of a tactical nuclear weapon (a prospect Budanov dismisses out of hand, blithely assuring me that US intelligence doesn’t believe it either). That’s also why the US has not yet given Ukraine the long-range missiles and planes that could cut off Crimea.

Yet while this is not a war between NATO and Russia, and western leaders are determined not to make it so, Joe Biden’s dramatic visit to Kyiv on Monday shows just how far the credibility of the West is now at stake in Ukraine. A year ago, almost no one outside Ukraine thought it could become a member of NATO, and France and Germany opposed even accepting it as a candidate for the EU. Ukraine is now an accepted candidate for EU membership. In Munich, I heard growing support for NATO membership too.

It will take a long time, however, to convince all thirty NATO members — including Hungary’s Putin-lite leader, Viktor Orbán, and Turkish dictator Recep Tayyip Erdoğan — to agree. But Ukraine needs hard security now. Apart from anything else, there will be little serious foreign investment without it. So in Munich, General David Petraeus argued for Ukraine to be given interim hard security guarantees by a US-led group of NATO member states. This is surely right. The only way to get to a strong, free, prosperous Ukraine is for European powers such as Britain, Poland, Germany and France to join the US in bridging the gap between the end of hostilities and the country’s eventual full membership in the two key institutions of the West.

By the same token, only that commitment would give the West the standing to privately encourage Ukraine to make any painful compromise that might be needed — at least for the time being — to end the war this year with a clear Ukrainian victory.

There is no risk-free way forward. There’s a risk in Ukrainian forces threatening Crimea and western countries offering Ukraine hard security guarantees. There’s a risk in allowing Putin’s grinding war of attrition to continue into next year, with Xi Jinping possibly drawing the conclusion that armed aggression pays. We need the wisdom and the courage to recognize that, in the long run, the second risk is greater. Fear is a bad counselor, Pope John Paul II used to say, and the message to the West, not just from Ukrainians but from the Baltic and East European leaders who know Russia best, is “Be not afraid!’ As we saw again in the Russian leader’s state of the nation speech this week, Putin is trying to intimidate us. Don’t let him succeed.

Timothy Garton Ash’s Homelands: A Personal History of Europe is published on May 23. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.