This article is in The Spectator’s February 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.

Was there ever a more audacious album title than Arthur, or The Decline and Fall of the British Empire? The name of the Kinks’ 1969 masterpiece could almost be described, in Sixties vernacular, as ‘far out’. But just two years after the lysergic hurricane of 1967, the content of Arthur was ‘far in’, even by the Kinks’ distinctly un-psychedelic standards. Not for them the late Sixties’ return to Americana of the Stones (Beggars Banquet), the Band (Music from Big Pink) and Dylan (John Wesley Harding). The Kinks’ state-of-the-nation meltdown dived into Ray Davies’s resolutely British and monochrome psyche, beyond the pastoral of Village Green Preservation Society (1968), turning left at the kitchen sink of Something Else (1967) and ending up on a floral sofa in the dark parlor of a Victorian terraced house in the ungroovy north London suburb of Muswell Hill. No reefer smoke in the air, just braised beef, boiled cabbage and suet dumplings.

Arthur’s cover, rendered in unbecoming shades of British Empire beige, was adorned with a King George V mug. And Arthur is nothing less than a history lesson. By 1969, Churchill was dead and the Kinks, as an album group, were toast. Something Else contained Ray Davies’s greatest composition, ‘Waterloo Sunset’, a massive hit in the UK and Europe, but the album sold poorly. The sales of Village Green Preservation Society were even worse. The Kinks, whether they liked it or not, were seen as a singles band. On Arthur, Ray Davies, his brother Dave on lead guitar, drummer Mick Avory and new bass player John Dalton had everything and nothing to play for.

Arthur’s roots lay in a television play for which Ray was asked to write the soundtrack, to be directed by Leslie Woodhead, whose early gigs included filming the Beatles at the Cavern. Somewhere in the Kinks’ Khaotic Kareer, the play got lost, leaving Ray with the concept. The story of Arthur Morgan is loosely based on the Davies’ brother-in-law Arthur Anning, whose emigration to Australia in 1964 with their sister Rose had earlier inspired Ray’s ‘Rosie Won’t You Please Come Home?’ Arthur Morgan sits and broods about fighting for his country, about his brother killed on the Somme and his son killed in Korea, about being abandoned by his other son Derek who is emigrating to Australia, about being abandoned by Churchill and stranded in a society that he doesn’t understand and that doesn’t want him. Far out Arthur may not be, but heavy and heartbreaking it is.

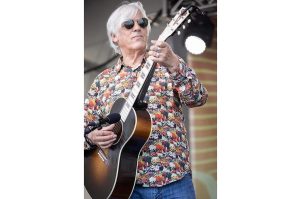

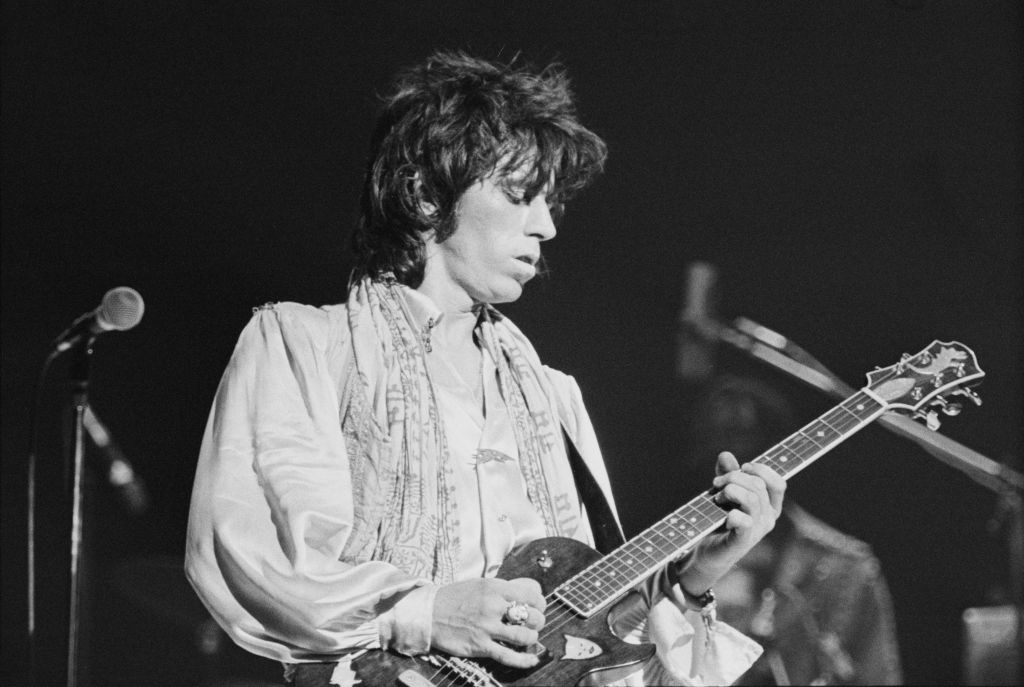

The Kinks’ genius lay in the power play between Ray and Dave Davies and the mighty drums of Mick Avory. To describe that connection as ‘interplay’ is to miss the point about the brutal beauty of the Kinks, as of all rock. Regardless of the subtlety of Ray’s songs, the Kinks at their best approached the music like soccer hooligans. Just listen to Dave’s off-mic feral shouting during ‘Victoria’. Many of the main players in 1960s British groups were lower- to upper-middle class: the Stones, the Who, the Pink Floyd. Two weren’t: the Beatles (working class, tough, smart and from Liverpool) and the Kinks (working-class London yobs, self-educated and hyperintelligent).

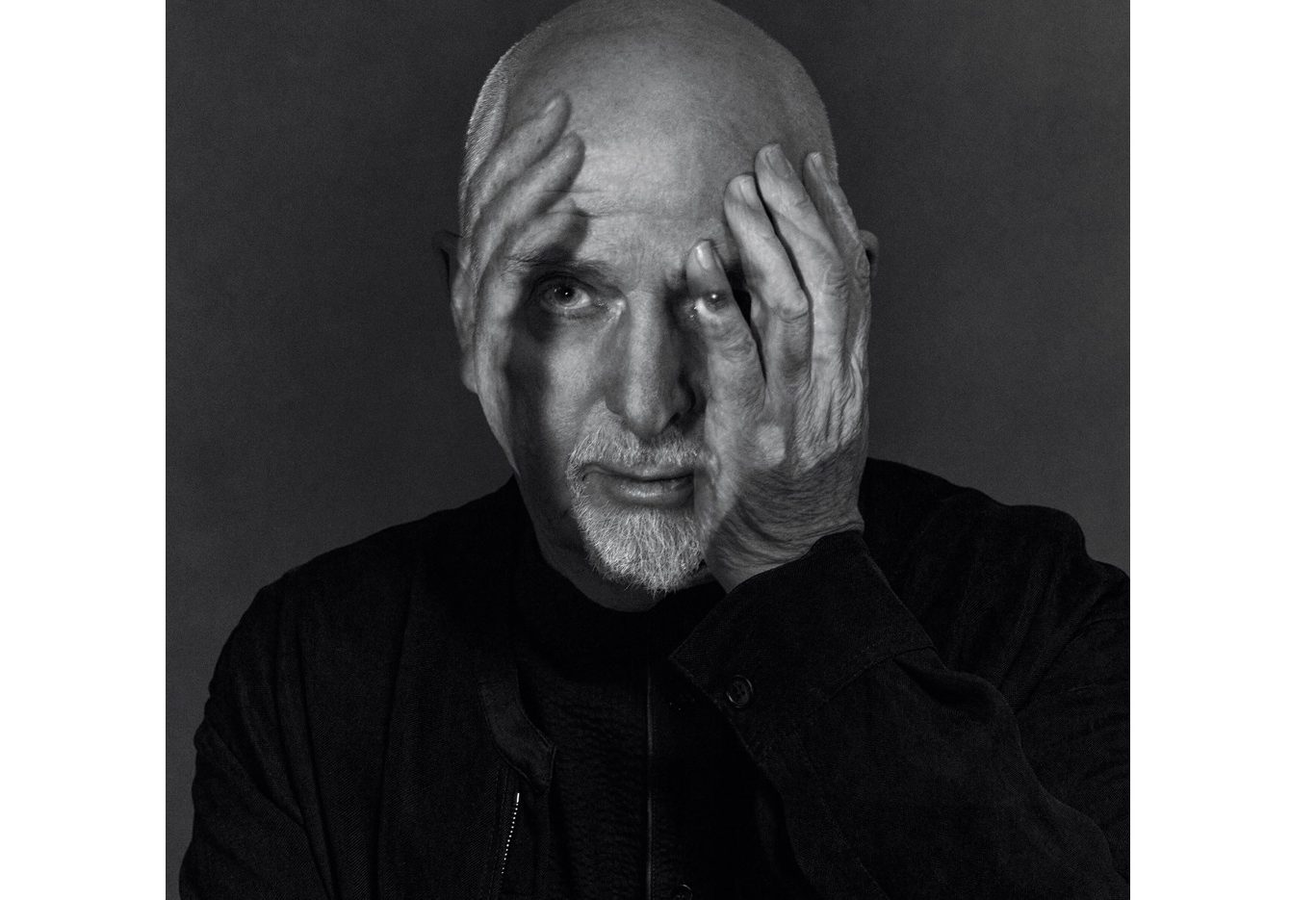

Arthur is now 50, maybe a little older than Arthur Morgan was in 1969. In the anniversary reissue you get so much extra Arthur for your buck that if you listen to it all in one sitting, you too may have an Arthur Morgan breakdown. That’s before you even get to the two new recordings by ‘Ray Davies with the Doo Wop Choir’. (Ray, you’re spoiling us.) The pick of the extras is ‘The Great Lost Dave Davies Album’, which actually is pretty great and, astonishingly, was recorded simultaneously with Arthur. Dave admits he couldn’t really be bothered with his solo album and just liked being in the Kinks: a telling insight into the Davies brothers’ weird and mutually aggravated dependency.

Many of 1969’s great albums are receiving reconsideration and reissue: the Stones’ Let It Bleed, the Fabs’ Abbey Road and the Who’s Tommy, which in the event pipped Arthur to the post in the conceptual stakes. Much as I dig the big three, can anyone say that a pinball-playing deaf, dumb and blind cult leader has any relevance to anyone who didn’t play a Bally table? And while Abbey Road’s final medley may be a production masterpiece, it’s not really about an awful lot — unlike Arthur. Sadly, many of us can relate to a middle-aged man brooding on his failed life in a world he no longer understands.

This article is in The Spectator’s February 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.