When James Ellroy’s L.A. Confidential appeared in 1990, it introduced us to a world of blatant corruption, casual racism and routine police brutality that, a year before anybody ever heard of Rodney King, might have seemed fanciful to some. Set in the early 1950s, the novel was a landmark in neo-noir writing, in which historical detail mingled with pacy fiction to conjure up a city that was both highly glamorous and rotten to the core. At the same time, Ellroy’s staccato, near-telegraphic prose drove the action relentlessly onwards, with an urgency that seemed designed to swamp not just the reader but also the protagonists themselves with noise, movement and a lowering, inescapable sense of doom.

For Ellroy, this brutal, sleazy world was personal: growing up in Los Angeles, he had not only witnessed its violence first-hand but, at the age of 10, had lost his mother, Jean, in a rape-homicide case that was eerily reminiscent of the infamous Black Dahlia murder, on which the L.A. Quartet’s first volume was based. Now, with This Storm, Ellroy redeploys some of his original cast, while adding a whole new layer of sinister figures, including historical players who, in various ways, helped shape the America we know today. (A helpful dramatis personae is included as an appendix, offering some provocative home truths about the nature and extent of corruption that has always haunted American political life.)

The book opens, in inimitable Ellroy fashion, with a no-holds-barred alcohol and drug-fueled party at New Year’s Eve, 1941: as America prepares for war, Los Angeles prepares to reap the rewards, of which the most lucrative, for now, is the routine business of relieving Japanese-American citizens of their valuables before dumping them in internment camps. Meanwhile, the city is experiencing an unusually powerful rainstorm that instigates a seemingly routine murder investigation, after a body is washed out of the mud in Griffith Park; it also provokes a naval officer, named Joan Conville, to make some unexpected career changes, after she ploughs into a truckful of Mexican workers while driving under the influence.

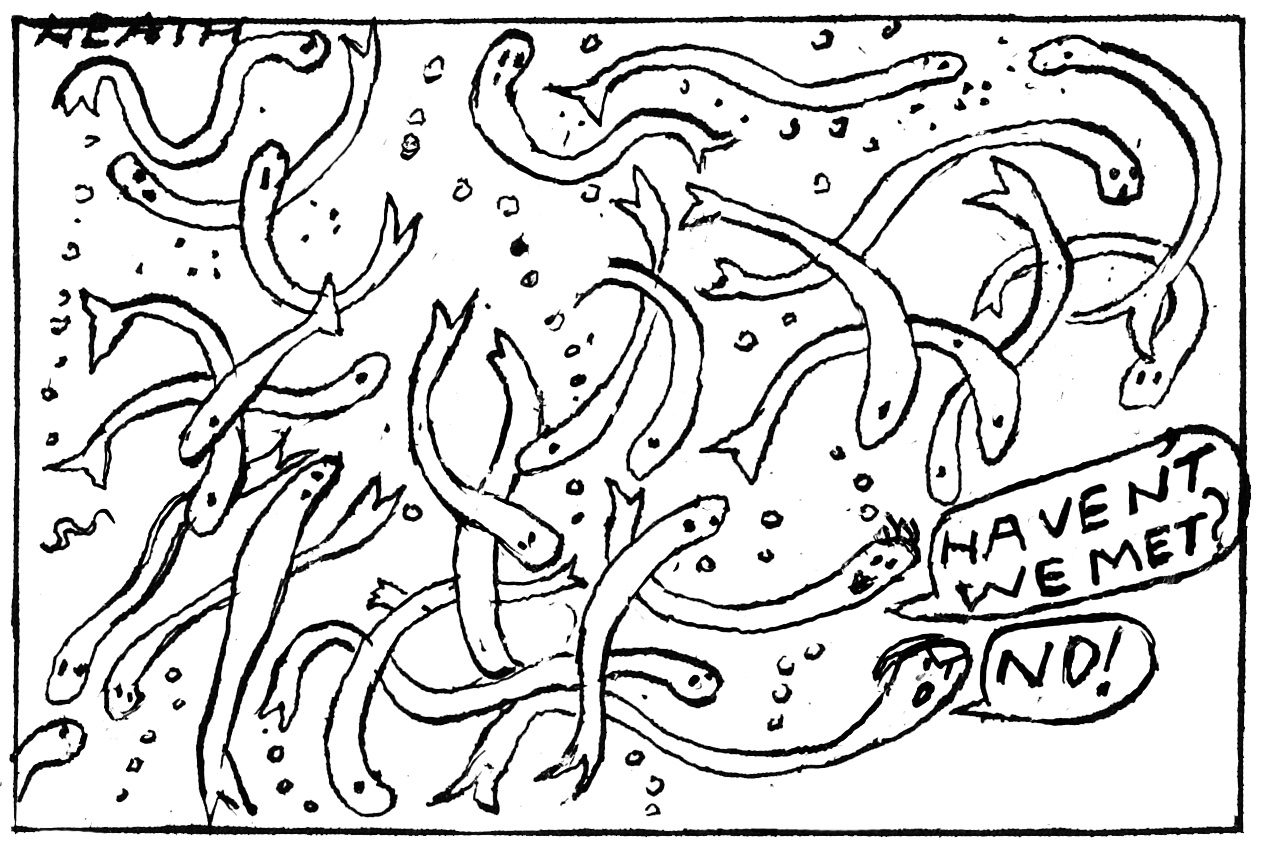

From these seemingly random events, Ellroy guides the reader through a series of strange, sometimes bizarre alliances and accommodations, as his assembled crew of pimps, enforcers, conmen, dealers and shameless war profiteers pursue their several conflicting goals.

Without a doubt, Ellroy aficionados will love This Storm. Others may baulk at its length and complexity, or at its headlong momentum. Possibly, in an era when many readers complain if they cannot find likable or ‘relatable’ characters in a novel, there will be those who dislike the fact that everyone here could be described as morally wanting (to put it kindly). Yet surely it is one of the uses of fiction to explore, if not to rectify, the moral failures of any age. At the end of This Storm, a man is brutally and systematically beaten by a pair of Los Angeles police officers; at this point in the proceedings, their superiors have seemingly logical reasons for allowing them to act in this way and they are able to do so in the full confidence that there will be no consequences.

Similarly, in the closing weeks of 1942, a 44-year-old public accountant named Stanley Beebe was beaten so severely while in LAPD custody that he died of his injuries — yet not only were his attackers acquitted, but the authorities even claimed that Beebe’s wife had murdered him when he was released into her care after the beating. At the time, the LA police chief, one Clemence B. Horrall (who appears in This Storm and in Ellroy’s previous novel, Perfidia), was widely recognized as irredeemably corrupt; but it took seven more years before he was forced out of office, after perjuring himself before a grand jury investigating the Brenda Allen vice ring. (Allen also appears in a number of Ellroy’s novels.)

So it continues, with one sorry tale of power and its abuse dovetailing into another, and gradually we begin to see the patterns, all the ways in which those in high places protect themselves and their lackeys, at least for as long as they are useful. The characters we meet in This Storm may not be relatable, but, for those of us still following the news, they are all too often eerily familiar and their methods need to be understood.

What Ellroy shows us, time and time again, is not only the ugliness of corruption but also the shame that infects an entire society when the guilty are permitted to go about their business so brazenly and with such a clear sense of entitlement that we no longer recognize what is right and what is most surely and inarguably wrong.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.