is only important from a Shakespeare’s-birthplace point of view. Architecturally it is a nullity beside the cathedrals of Beauvais and Laon, Albi and Marseille, Rouen and Clermont-Ferrand (a sinister marvel of black tufa).

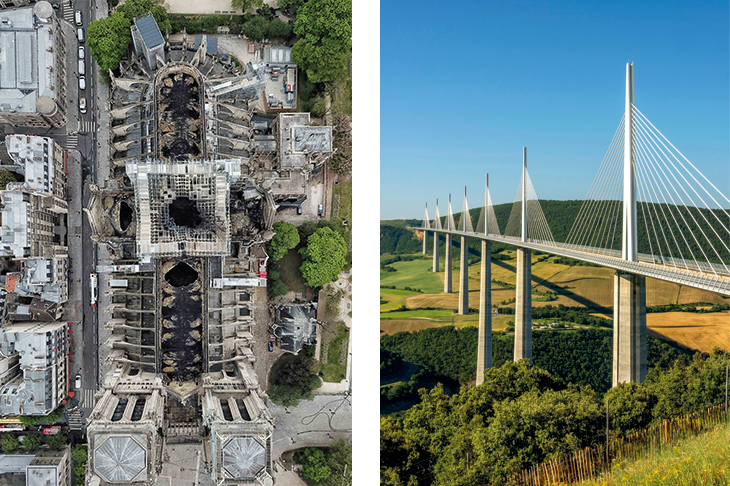

The ashes of the cathedral are now the site of a proxy struggle between some of the greatest fortunes on the planet. The struggle has begun with the architectural competition announced by the widely loathed Macron and the so far less loathed PM Édouard Philippe. How will the competition be conducted? Who will select the committee that will select the committee that selects the architect or engineer whose name will get attached to the building like Viollet-le-Duc, who restored it in the mid 19th century with all the nous of a mediaeval surveyor enjoying the good fortune to live under the July monarchy. William Burges, an architect of genius, described Viollet-le-Duc as ‘a great scholar, an average architect and a disastrous restorationist’.

A verdict which ought to be recalled by that constituency that demands Notre-Dame should be rebuilt ‘just as it was’. Just as it was when? With the exceptions of Salisbury (spire apart) and Amiens, the great cathedrals have been built over many centuries in many styles: they are accretive collages. It should, however, also be recalled that Viollet-le-Duc, unlike both his English Tractarian contemporaries and the aesthete Burges, was a rationalist: restoration was precisely not copying what had once been there and was now destroyed. It was the ‘re-establishment of a structure as it had never been before’: in other words, just as it wasn’t.

He was a technocrat avant la lettre who considered the gothic to be a programmatic system of building rather than a sacred duty. An evidently inanimate system of minerals to which feeling, memory, national outpouring, godliness, beneficence etc. cannot possibly be ascribed — save by those who do so. From a practical point of view, the obstruction to an imitative restoration is that France, like any modern country, currently suffers a shortage of highly trained mediaeval construction workers.

So Philippe and Macron spoke of the restoration taking into account ‘today’s techniques’ and being achieved ‘within five years’: where will they be then? They happily admitted that France is no longer a land of wandering masons from la Creuse. There are indeed hardly enough craftsmen to maintain historic structures in normal circumstances, structures that are in perpetual mutation and, in many instances, fakes of themselves, so comprehensively have they been worked on. All this hints at a governmental bias towards an architecture that looks gingerly forward.

The gothic does not have to be wrought of limestone, wood, alabaster and lauzes. Viollet-le-Duc militated for iron as a building material though he didn’t use it as successfully as Victor Baltard, whose Halles were destroyed in the 1970s but whose splendidly gross Saint-Augustin remains.

Artisan drought aside, the major hurdle to ‘just as it was’ will be the nationwide, perhaps worldwide, scream of accusatory architects: ‘Pastiche!’ The architectural doxa decrees that pastiche is a Very Bad Thing Indeed. The collective convention forgets that the history of architecture is the history of pastiche and theft: Von Klenze’s Walhalla above the Danube is based on the Parthenon; George Gilbert Scott’s St Pancras borrows from Flemish cloth halls; Arras’s great squares are imitations of themselves. It forgets, too, that after a few decades the bogus ape becomes indistinguishable from the authentic ape, which of course may not be all that authentic: how far back do you have to go before you strike the very kernel of authenticity?

The cultural objection to pastiche is that through the century and a quarter of modernism’s paramountcy, architects, a flocking species, have seldom dared to diverge, egregiously, from the mainstream that is nothing more than the old avant-garde without the built-in shocks. Those who have excepted themselves and have broken rank tend to be stubbornly eccentric or unconcerned about making a living even though they are perhaps more in touch with the tastes of the happily unreflective creatures patronized as ‘ordinary people’ who enjoy fantasies, follies, Mariolatrous kitsch and Poundbury.

Macron’s overworked catchphrase ‘en même temps’ translates architecturally into the ‘both/and’ of postmodernism’s harbinger Robert Venturi and the ‘unity by inclusion’ of the Scottish ecclesiastical architect Ninian Comper. It can be read as a recipe for polite compromise or for an exuberant maximalism. The fire is extinguished but the fire goes on. It has legs. It is a god-given PR opportunity for a wobbling yet obdurate president — if he can work out how to seize it. Given that he only raises his head from the sand to demonstrate how out of touch he is it’s likely he won’t. His latest dumb wheeze, the proposed dissolution of the École Nationale d’Administration, of which he himself is an alumnus, has been met in the polls with 63 percent hostility. It has been rumbled as a crudely tokenistic gesture of anti-elitism by the elite of elites.

The rebuilding cannot risk such dodgy populism. It’s meant to last. Between the stylistic (and political) poles of copyist fidelity to the structure as it was till the early evening of April 15 and, say, the titanium scrapyards of Frank Gehry (billionaire donor Bernard Arnault’s man) there are countless options of idiom and strategy and there’ll be countless interests promoting them. One option that will not be explored, despite its romantic appeal, is that of leaving it ruinous so that nature can assert itself — but with nature in cities there come crack pipes and used needles.

It appears that no bookie is yet offering prices on the potential contenders for this prize. Here are a couple of punts.

Long odds: the New Yorker Mark Foster Gage is a farouche outsider, the most decoratively radical architect at work today; he has revived the lavish tradition of Burges, Gaudi and Coppede.

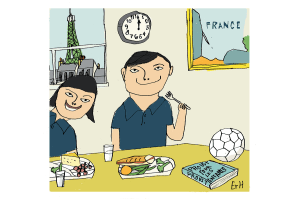

Odds on: the exemplary model for how to proceed is 500 miles due south of Paris. The Millau Viaduct is the greatest gothic structure of the past century: the clusters of cables form diaphanous spires. It’s an anthology of superlatives: highest, best, most startlingly beautiful. It took a mere three years to build. The combined ages of its creators, the engineer Michel Virlogeux and the architect Milord Foster of Thames Bank, is 155 years. They’re kids. Let them get on with it.

This article was originally published in The Spectator magazine.