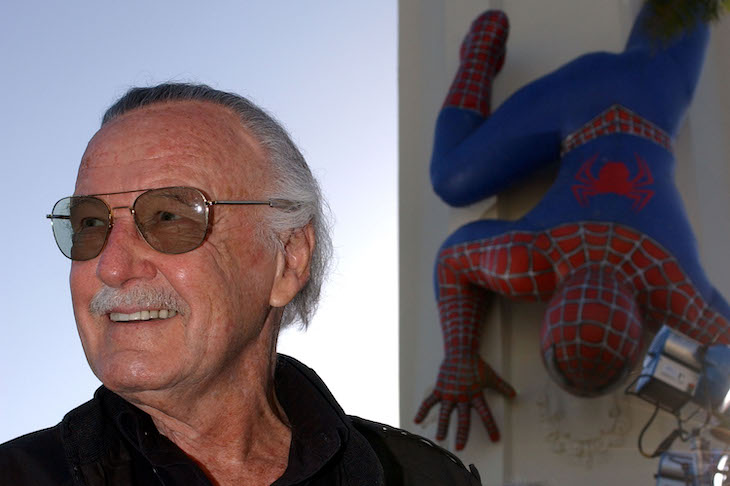

If there was one character who was omnipresent in the Marvel comic books universe, it was Stan Lee. Lee, who died on Monday, defined an exuberant, confident American era that seems to have vanished along with him. A member of the World War Two greatest generation, he played a decisive role in making comic books great again, starting in the 1960s, when he sought to reinvent the moribund genre with characters who bickered with each other when they weren’t worrying about their love lives.

Gone was the sterility of DC’s Superman, a paragon of perfection, to be replaced with ironic detachment and human foibles. Sometimes heroes were scared. Amazing Spider-Man 18 featured its hero cowering behind a building as Sandman pursues him. The cover read, ‘Why does Spidey cringe in helpless fear as the evil Sandman stalks the city’s streets?’ In the Fantastic Four, the mighty Thing would be plagued by the Yancy Street gang, a motley crew of boys and adults living in downtown Manhattan who would taunt their former leader when they weren’t showering him with rubbish. The Thing, for all his combativeness, also had a melancholy side; only his blind girlfriend Alicia could see his true humanity, even as his longtime scientist friend Reed Richards agonized over his responsibility for his transformation of Ben Grimm into a pile of rocks. On and on it went, superhero after superhero wrestling with his or her powers and deficiencies. With his zest for showmanship, Lee helped to turn the superhero world upside down; only decades later would the movie industry catch on, producing blockbuster after blockbuster based on the fecund imaginations of Marvel’s early creators, including seminal artists such as Steve Ditko, Jack Kirby, and John Romita Sr.

Each month ‘Stan’s Soapbox’ would appear in Marvel’s offerings, long after he himself had stopped writing the Fantastic Four, Amazing Spider-Man, and the other characters he had helped create. Whatever his actual share of the credit for the FF, as they were known, or other superheroes — endless debates surround the precise amount of glory that should be doled out to Lee and his collaborators — his irreverent spirit suffused Marvel. But so did his conscience. My chum James Rosen, who is not only a crack journalist but also a gifted artist, recently alerted me to a book called We Spoke Out that was published this year and reprints comic books about the Holocaust that appeared from the 1950s down to the present. The foreword is written by Lee. In it, he offers what amounts to his credo: ‘People don’t usually associate so profound and forbidding a topic as the Holocaust with the costumed superheroes and bombastic villains who inhabit the world of comic books. But the truth is that those colorful characters aren’t the only residents of the comic book universe, and comic books can serve more purposes than entertainment alone.’

Indeed they can. One of the issues of the Amazing Spider-Man that Lee could take real pride in was number 96, which was the first to appear without the Comics Code Authority stamp of approval in the upper right-hand corner of the cover. Instead, Marvel’s transgression, at least as far as the code was concerned, centered on the depiction of a young black youth teetering on the edge of a tall building as Spider-Man spots him and thinks to himself, ‘I got here just in time. The poor guy’s stoned right out of his mind.’ Needless to say, Spidey rescues the fellow midair, prompting a police officer to ignore an outstanding arrest warrant for the webslinger. He declares, ‘I’d turn in my badge before I’d bust him — after this.’

There was often a strong dose of moralism in Lee’s work. In the same issue, Lee observed in his soapbox that Marvel had made a conscious and deliberate decision to tackle topics that it might have shunned in the past. It amounted to a declaration of confidence in readers, a sign that Marvel was going to forge its own path, regardless of what the bluenoses at the Comics Code Authority might think. ‘During the early years of Marvel’s growth,’ he wrote, ‘our more aware readers used to ask why we didn’t editorialize more, and I’d answer that we didn’t feel it was within our purview. However, as time went by, and we realized that our readership was far more mature, far wiser than anyone had suspected, we began to touch upon real issues, real problems that confront this woebegone world of ours.’

In Captain America 122, Cap ponders his status as a symbol of patriotism in the wake of the Vietnam War: ‘I’m like a dinosaur — in the Cro-magnon age! An anachronism — who’s outlived his time! This is the age of the anti-hero — the age of the rebel — and the dissenter! It isn’t hip — to defend the establishment! Only to tear it down! And, in a world rife with injustice, greed and endless war — who’s to say the rebels are wrong…I’ve spent a lifetime defending the flag — and the law! Perhaps — I should have battled less — and questioned more!’

Marvel was also quite progressive on racial issues. In his excellent book Comic Book Nation, for example, Bradford W. Wright reports that ‘in 1972, on Stan Lee’s initiative, Marvel took a chance with a new kind of black superhero. Luke Cage, Hero for Hire featured an African-American superhero who had greater ‘street credibility’ than his predecessors. While the Black Panther was a stately African prince…Luke Cage was a lower-class black man from the ghetto.’ The comic book was a bust. But Lee never hesitated to take a chance or to update his characters or to create a sense of camaraderie with readers, as though they were unofficial co-conspirators.

He was the branding expert par excellence. He mainstreamed Spider-Man, going from the nerd that Ditko had created, to a more manly and mainstream version with John Romita in issue 39.

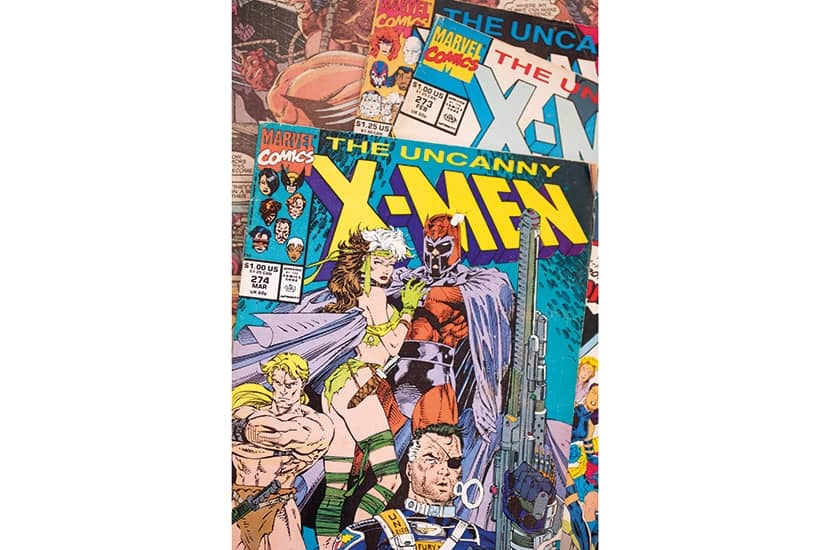

In his soapbox, he would sound off about everything under the sun, sometimes confessing that he had run out of inspiration. Tonight, as I flip at random through an old issue, The Uncanny X-Men 121, Lee announces, ‘Forgive me gang — it’s been a tough day!’ But the days when he ran out of steam were seldom.

The innocence of the early days of Marvel can never be recaptured. The back issues have become a commodity, immured, more often not, in slabs of plastic that carry a grade up to 10 testifying to their condition and value. The prices for the choicest volumes are seldom less than in the six figures. The comic book industry has come of age. It owes much of its success and legitimacy to Stan the Man, as he was called. When I attended a comic book convention a year ago and made an impulse purchase of a prized issue of Amazing Spider-Man 121, the dealer asked, ‘Are you going to get Stan to sign it?’ Though the grandmaster of Marvel was in his mid-nineties, I immediately knew to whom the seller was referring. Lee may not have been a superhero, but he was definitely a titan.