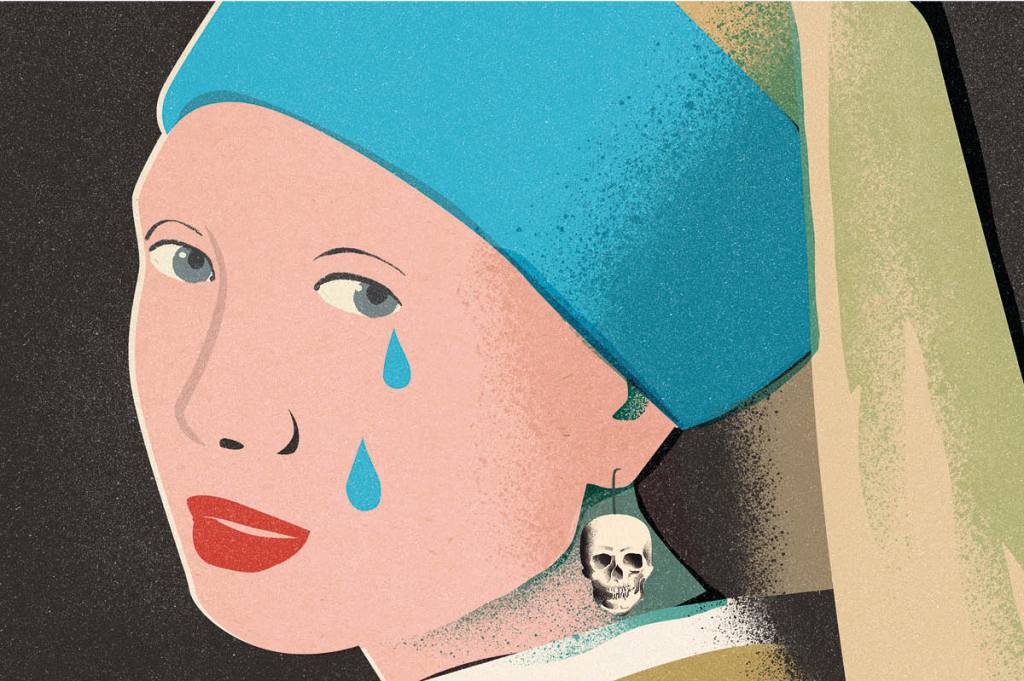

The seventeenth-century Dutch painter Johannes Vermeer is certainly having a moment, thanks to the enormous popularity of the retrospective of his work that concluded at the Rijksmuseum in June. Demand to see the gathering-together of twenty-eight of the thirty-seven currently known paintings by the Old Master far outstripped supply; the show sold out within two days of opening, and scalpers were allegedly reselling tickets online for hundreds, even thousands, of dollars.

It’s certainly not difficult to understand why people would flock to see Vermeer’s work, thanks to his beautiful brushwork and sensitively lit compositions. I suspect that a significant aspect of Vermeer’s contemporary appeal, like videos of ASMR whisperers or Italian grandmothers cooking, is the visual escape that the artist provides. The tranquility of his images somehow helps us feel good about ourselves, and to forget about the unpleasant aspects of life for a while. To my mind, however — and with no disrespect intended toward Vermeer — the painters whose work I’ve always been particularly drawn to are capable of providing something much more profound than eye candy.

In his book History and Its Images (1993), the English art historian Francis Haskell recounted the renewed interest in and appreciation for the apocalyptic images created by Albrecht Dürer, the greatest of the German Old Masters, in the years following World War One. “Men had seen ships torn apart by torpedoes fired from beneath the seas,” he notes, “cities battered by bombs dropped from above the clouds; soldiers choked by yellow clouds of poison gas or flattened by armor-plated tanks; kings and emperors fleeing into exile or being massacred with their families; revolutions threatening to turn the world upside down.”

No wonder, then, that those who survived found renewed meaning and relevance in Dürer’s representations of the end of the world. No wonder, too, that many at the time called for turning away from the obsession with materialism that threatened to bring about so many of these horrors. Look around today of course, and you will find that many have long forgotten this lesson, making Dürer’s images of traumatic suffering just as relevant to the present.

It’s an example of how the Old Masters can force us to look at ourselves through the presentation of subjects which, on some level, we would probably prefer not to look at, but are simultaneously drawn to ponder. Crowds do not line up for hours at the Sistine Chapel, after all, just to see a pretty picture which — whatever one thinks of his ceiling — Michelangelo’s “Last Judgment” certainly is not. And the great painters often achieve truth without flinching themselves: Caravaggio’s Judith doesn’t step offstage to murder Holofernes, for example, and Zurbarán doesn’t turn away as he presents us with the strung-up, tortured figure of Saint Serapion. From a purely artistic standpoint, there’s not much new under the sun: Game of Thrones was not exactly innovative, visually speaking, when we see the legacy of artists such as these.

Despite the overwhelming dominance of modern and contemporary art in recent decades, there are signs that some people are, finally, coming to a renewed appreciation of the powerful draw of older works of art, as both the popular and critical reaction to the Vermeer show suggest. With this comes the possibility that a greater effort to appreciate the best art of the past is growing, after so many years of the art establishment languishing in the celebration of largely self-indulgent twaddle.

There are reports of increased sales of Old Master paintings and drawings to new and younger collectors, and alongside the Vermeer show, recent exhibitions of the work of Old Masters such as Cranach, Da Vinci, Donatello, El Greco, Raphael and Tintoretto have been pulling in crowds looking for something more than a funhouse in which to take selfies. There is clearly a hunger for something fundamentally deeper in meaning than either self-aggrandizement or self-pity.

Perhaps this shift is due, in part, to a desire to find a way to navigate through the often angry and violent society in which we live, where individual human beings are often publicly dismissed (or worse) when they are seen as creating a hindrance to the plans or prerogatives of others. This all-too-human tendency has been around for quite a long time, as W.H. Auden observed in his 1939 poem, “Musée des Beaux Arts”:

About suffering they were never wrong, The old Masters: how well they understood Its human position

One of the works that Auden alludes to is a copy of Pieter Bruegel the Elder’s “The Massacre of the Innocents,” which he saw during a visit to Brussels in the winter of 1938. The original picture is at Windsor Castle, while that in the Brussels museum was painted by the artist’s son, Pieter Bruegel the Younger. In that version, images of dead infants and children had been painted over or scratched out at some point, as the picture was considered too politically charged by its one-time owner, the Holy Roman Emperor Maximilian II, and too shocking for people in general to stomach.

As a result of this selective editing, instead of their dead progeny, we see objects such as bags of grain or household items snatched from the arms of howling parents and littering the snow-covered ground. It’s a testament to the power of Bruegel’s original depiction that, even during a decidedly horrific period marked by brutal wars of religion, these graphic images of suffering and trauma were considered too powerful to remain unaltered.

Although based on the story contained in the Gospel of Saint Luke, Bruegel transposed the setting of the picture to sixteenth-century Holland. The troops are not the first-century Hasmonean guards of Herod the Great, but mercenaries working for the Habsburgs; the townsfolk are not the residents of ancient Bethlehem living under Roman rule, but Dutch villagers of Bruegel’s day, living under Spanish rule. The decision to treat the Biblical story in this fashion was an effort to make the suffering and trauma experienced by people who had lived 1,500 years earlier more relatable to Bruegel’s contemporaries, as they tried to understand and come to grips with the suffering they were enduring. It is as if an artist working today set the painting in Mariupol or Kherson.

In many of their most powerful and enduring images, the Old Masters did not shy away from asking “Why?” in the face of suffering and trauma. We can see just how long that search for meaning captured the Western artistic imagination by juxtaposing images by two very different painters who “bookended” this lengthy period: Giotto di Bondone and Francisco Goya. In most respects Giotto and Goya could hardly be more different, though interestingly enough, each used a similar artistic device to question the meaning of suffering.

Giotto was the first Old Master to paint fresco cycles, and his depiction of “The Lamentation of Christ” (c. 1305) from the highly complex program of the Arena Chapel in Padua, informed by the writings of St. Augustine, is strikingly immediate in its representation of pain and grief. In this image, Jesus is laid in the lap of his mother, and the figures surrounding this pietà bear deeply emotional expressions. Even the tiny angels in the sky are writhing in agony and sorrow as they contemplate the scene. The Crucifixion is over, and for the disciples gathered around the tortured body of Jesus, this is a moment of unmitigated trauma. Notice how Giotto draws our attention to the one particularly dynamic figure in the scene, the young man situated at center right. This is Saint John the Evangelist, who the night before had laid his head on Jesus’s chest at the Last Supper. Alone among the Twelve Apostles, he returned to watch the execution of his friend. His arms are flung wide as he leans forward, and he seems to cry out, “Why?” in a physical demonstration of his disbelief of the disaster that has just occurred.

Goya’s “The Third of May, 1808,” has sometimes been considered the very last Old Master painting, and the beginning of something new in Western art. The painting shows a group of peasants being executed by firing squad outside Madrid, following attempts to revolt against French troops during the Napoleonic occupation of Spain. The artist provides no apotheosis here to soften the blow: death comes brutally, with no crowns of martyrdom, mourning angels, or shafts of celestial light.

Like Giotto in his “Lamentation,” Goya directs our gaze to the figure of a young man, this time located at the center left. Several of his companions are already dead or dying around him, as the soldiers fire another volley. Just like Saint John in Giotto’s painting, his arms are flung wide, and he bears a look of horror and incredulity on his face. He, too, wants to know the answer to the question, “Why?” Handsome portraits and beautiful still lifes are important. However, it is in their most profound works that the Old Masters speak to us about suffering and trauma in a way that is as relevant as it was to the audiences of their own times. We, too, have witnessed bellicose atrocities, the abuse of other human beings as a means to an end, the impact of deadly pestilence, unjust executions and violent unrest. Suffering as a universal experience hasn’t really changed in its fundamentals from the time of the Old Masters to ours.

Auden observed that the Old Masters understood suffering, including its ironic mundaneness from time to time because of how often it happens in the face of indifference or sheer obliviousness. Yet it seems to me that what the Old Masters really understood about suffering is that it comes to all, no matter how we may try to avoid or evade it. Finding a way to deal with that reality once it arrives is a fundamental part of the challenge of being human.

For some, the answer to the universal “Why?” can be found in the belief that there is something beyond the dingy, limited present. For others, the trauma of suffering bears no greater purpose whatsoever, and is best avoided for as long as humanly possible. Ultimately, the choice of how we approach suffering and trauma in our lives is made on an individual basis. If we allow them, however, the Old Masters can help us to visualize that choice, not only with respect to how we treat ourselves, but also with regard to how we interact with those around us.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2023 World edition.