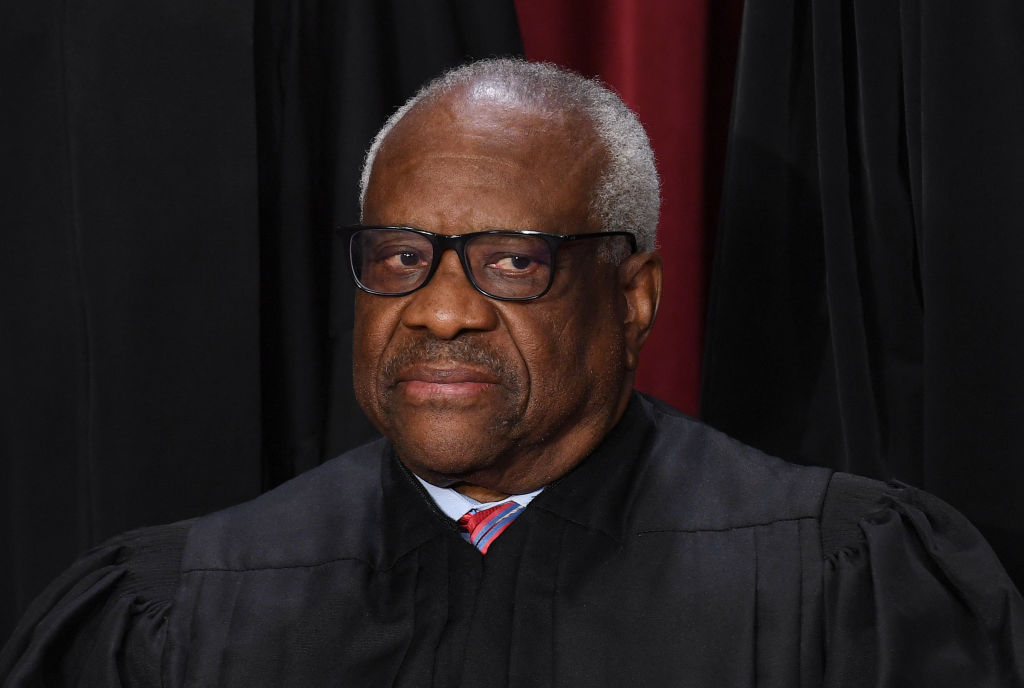

Anyone looking for a villain in the Supreme Court’s decision to strike down decades of affirmative action precedent will find one in Clarence Thomas.

Critics have long found Thomas’s politics vexing in light of his race, a frustration that has only grown more pronounced as the affirmative action decision drew near. To hear his detractors tell it, Thomas was himself the beneficiary of affirmative action policies, both as an undergraduate at the College of the Holy Cross and later at Yale Law School. That Thomas could have such an experience and still strike down race-based admissions policies seems to make him a hypocrite — and an ungrateful one at that.

Holy Cross president Vincent Rougeau’s May 28 Boston Globe op-ed offers a glimpse into the coverage we can expect in the coming weeks. The piece, titled “Clarence Thomas was a beneficiary of race-based admissions at my school,” aims to paint the justice as a hypocrite in order to discount his opposition to race-based college admissions. It’s a tired, inaccurate narrative that critics trod out whenever they want to attack Thomas for his views on race.

Those who wish to denigrate Thomas lean on a very selective reading of the justice’s biography. They’ll note that Thomas was one of twenty black students recruited by Holy Cross professor Fr. John Brooks, S.J. in 1968. They’ll note, as Rougeau does, that Thomas was “the beneficiary of the most overt example of race-based admissions I can imagine.” Armed with those two pieces of information, they’ll dismiss Thomas’s entire legal philosophy by smearing him as an ungrateful crank trying to pull up the ladder to success behind him.

There are several problems with this analysis, most notably that it ignores what Thomas himself has said on the subject. Thomas has written movingly about the “debt of eternal gratitude” he owes to Holy Cross in general and Fr. Brooks in particular — and Thomas’s gratitude stems in a large part from the fact that Fr. Brooks’s recruitment drive was not like today’s institutionalized affirmative action policies.

“I wasn’t part of some program to Fr. Brooks, I was a kid,” Thomas says. “Fr. Brooks tried to help us, but he never tried to work any issues out through us. He wanted the college to have more black students because it was the right thing to do.”

Indeed, it was precisely the fact that Thomas had a different experience at Yale that made him sour on affirmative action as it is presently understood. While Fr. Brooks took pains to make his black recruits feel like any other student, in New Haven, Thomas felt like a black student.

“I learned the hard way that a law degree from Yale meant one thing for white graduates and another for blacks, no matter how much anyone denied it,” Thomas writes in his 2007 memoir My Grandfather’s Son. “I’d graduated from one of America’s top law schools, but racial preference had robbed my achievement of its true value,” he wrote. It’s a point Thomas famously underscored by affixing a fifteen-cent sticker to the frame of his Yale Law diploma.

This cuts to the heart of Thomas’s objection to affirmative action, namely that it reduces students to their race, rather than viewing them as individuals. Thomas opposes today’s affirmative action policies precisely because they paint with a broad brush, prioritizing racial quotas over the type of holistic diversity Fr. Brooks went looking for when he set out in his 1965 Pontiac GTO in the summer of ‘68.

In striking down decades of affirmative action policy, the Court has made it possible to return to a more nuanced approach to race and college admissions, the kind Thomas benefitted from at Holy Cross.

Critics may see this decision, and Thomas, as cynical and regressive. But as is often the case, Thomas offers a more nuanced take than his detractors will admit. Would they only read his words, they would find that Thomas is not bitterly yanking the country backwards, but hopefully nudging it forward.

“While I am painfully aware of the social and economic ravages which have befallen my race and all who suffer discrimination,” Thomas writes in his concurring opinion in Students for Fair Admissions v. Harvard, “I hold out enduring hope that this country will live up to its principles so clearly enunciated in the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution of the United States: that all men are created equal, are equal citizens, and must be treated equally before the law.”

Tim Rice is associate editor of the Washington Free Beacon.