This newly translated novel by the Spanish writer Antonio Muñoz Molina is really two books, spliced together in alternating chapters. One is a deeply researched account of the squalid peregrinations of James Earl Ray, who spent two months on the run after murdering Martin Luther King, Jr., in 1968. The other is a memoir charting the gradual attainment of personal and professional happiness on the part of the author himself.

The reader feels confident that both protagonists will eventually arrive at their historically appointed destinies: handcuffs at Heathrow airport for Ray; a career as a celebrated author for Muñoz Molina. But considerable suspense surrounds the question of what on earth these two stories will have to do with each other. The mystery only deepens as the crux of the book is revealed to be the bland coincidence that both men, at different times, travelled to Lisbon.

Lisbon, then, is the main setting. Ray is there blundering in and out of flophouses and trying to find passage to Africa, where he hopes to continue his career of shooting at black people as a mercenary in colonial wars. Muñoz Molina first visits in 1987 to find the backdrop for what would be his breakthrough novel. He is also committing offences against his first marriage. The two men drink in would-be similar bars. They also read distantly related stuff. Muñoz Molina likes the metaphysical detective stories of Borges and the existentialist noir of Juan Carlos Onetti; Ray pores over spy novels ‘where the brand of everything the characters carry or use is detailed’ (as well as autohypnosis manuals, and the adverts in Life magazine). They are both living in fantasy worlds, with ‘that delirious belief… that real life was elsewhere, that imagination is richer and more powerful than reality.’

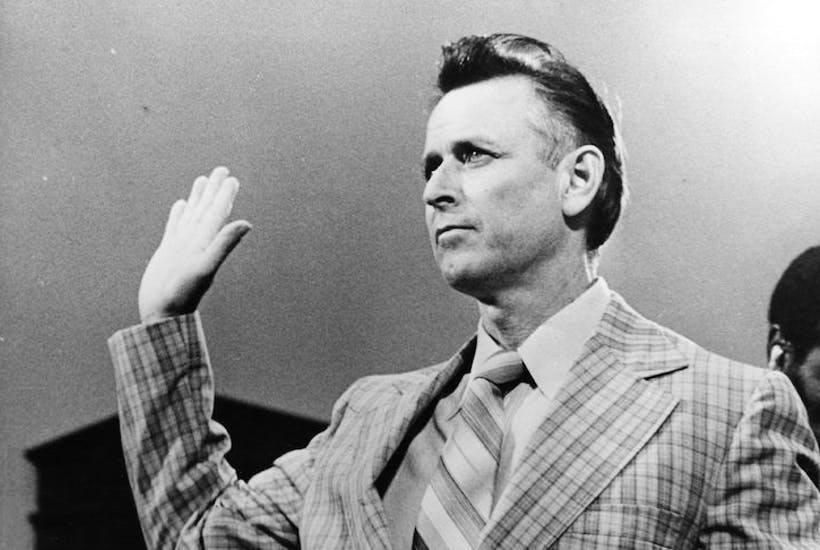

The parts about Ray are bleakly mesmerising. The parts about Muñoz Molina meander elegantly into ruminations on literature and the writing process. After Ray is captured, he too begins to write — reams of counterfactual autobiography in which a shadowy figure named Raoul was instead responsible for his crime. With clever sleight of hand, Muñoz Molina is at this point able to deploy paragraphs that could be referring to either protagonist. But the juxtaposition remains strangely arbitrary.

Meanwhile, a redheaded woman appears in the picturesque way that both men had perhaps dreamed of. She appears to Muñoz Molina, never to Ray: the novel is also a love letter to the author’s second wife. Later, this couple travel to the depressed city of Memphis, to visit the scene of the crime, the Lorraine Motel, where they find the National Civil Rights Museum, erected there in memorial. The broader history is thus opened up for the first time, eliciting an unexpected and magnificent finale.

The American civil rights struggle is a story of our species at its most noble and its most vile. With a shot fired from a bathroom reeking of ‘fermented urine’, a pusillanimous moron strikes down one of the finest human beings in history. The significance of this event, which finds its constant echo in atrocities up to the present day, is universal.

Across an ocean, decades later, a grateful man of letters finds marital happiness at the second attempt, and sees his children begin to navigate their adult lives. The deep connection between the stories is suddenly clear: as Muñoz Molina’s book demonstrates with an awkward power, it’s a connection that can, in fact, go without saying.