Imelda Marcos allegedly wants three words inscribed on her tombstone: Here Lies Love.

It’s a poetic expression made grimly baleful by the reality of the Marcos regime: Imelda and her husband Ferdinand ruled the Philippines with an increasingly iron fist from 1965-86, committing countless human rights abuses as they robbed the country’s coffers.

Yet the phrase has been borrowed by David Byrne and Fatboy Slim as the title of their musical about the Marcoses, Here Lies Love, now playing on Broadway (it premiered off-Broadway in 2013). Whether the phrase is used in earnest or irony is never quite clear in a show that apparently positions itself as a fun and fabulous karaoke dance party. That it is a dance party about a pair of murderous tyrants is both problematic and intriguing.

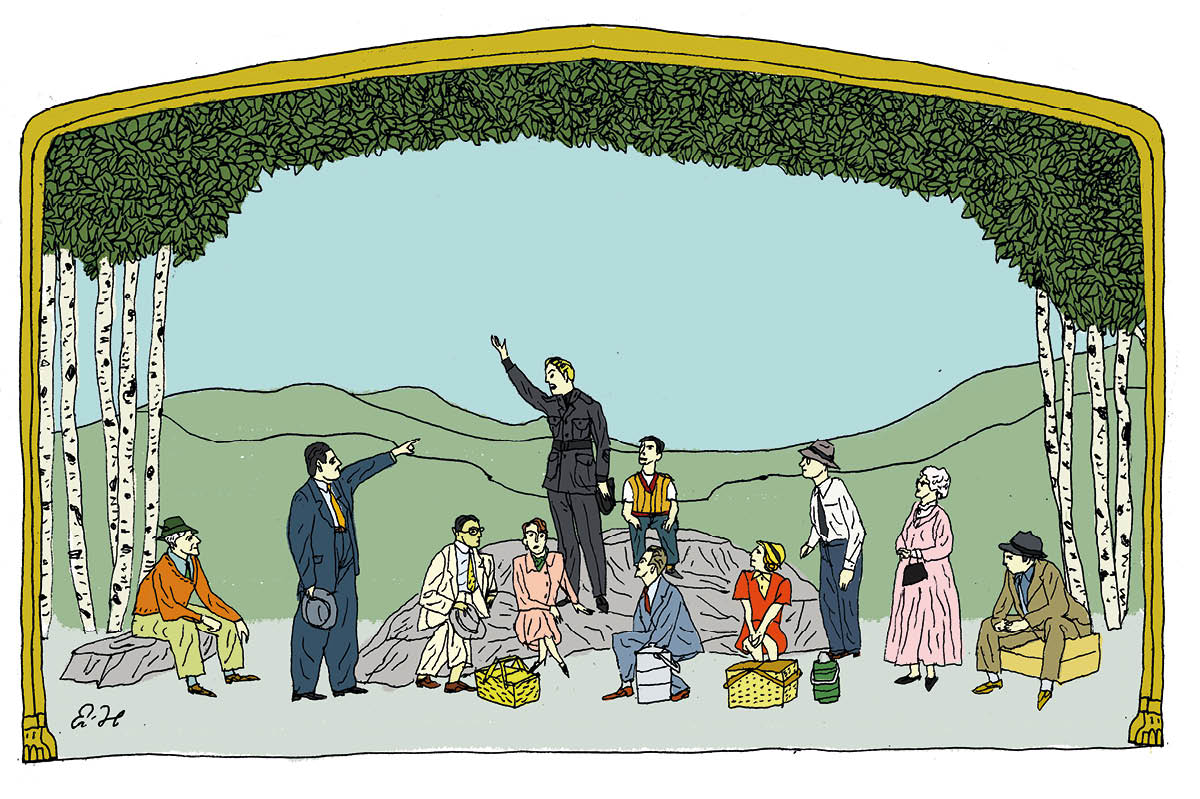

Central to Here Lies Love is audience immersion. In the Broadway Theatre, 900 orchestra seats were removed to make space for a standing dance pit. Staff in neon pink jumpsuits direct the hundreds-strong crowd on the floor with big grins and orchestrated whoops, encouraging them to jive to the music as the actors perform on a series of moving platforms.

While buying a seat in the galleries might be more comfortable and dignified — down in the pit I felt at times like a cow being herded — there is something strangely thrilling about being so close to the action: it is not often that you can see individual beads of sweat gather on a performer’s forehead.

The story follows Imelda Marcos’s life, from small-town teenage beauty queen to young, hopeful first lady and finally to middle-aged narcissist (the song “Why Don’t You Love Me?”, delivered to rebellious Filipino crowds, sums up her epic self-delusion). Tying it together, and providing the fodder for the entire concept, the composers use Imelda’s passion for all things disco; in Manila she even erected a dance floor on the rooftop of her palace.

Providing extra heft is Broadway’s first fully Filipino cast. Arielle Jacobs is beautiful and enticing as Imelda, and competently handles her megalomania; Jose Llana plays Ferdinand with greasy slickness. Leading the opposition is the tenacious Conrad Ricamora as Ninoy Aquino, a long-time critic of the Marcos regime, bristling with sinewy energy.

Here Lies Love has no truly standout songs, nor does it have the gravitas of Evita, its closest musical cousin, which does a better job of rounding out the characters of Eva Perón and her Argentine dictator husband Juan. It never humanizes the Marcoses, who have no interiority; they never grapple with consciousness, never show glimpses of vulnerability, never truly demonstrate how power can become intoxicating. They are too cartoonish and too glossy.

But it is a spectacle, and an ambitious one at that. The onstage costume changes are clever, thrilling even; the DJ and master of ceremonies Moses Villarama does a good job of firing up the crowds, the dancers are energetic and the actors gung-ho.

All this is tempered by some hard-hitting techniques designed to highlight the Marcoses’ smarminess and cruelty. These range from filming the actors as they deliver speeches, with the live broadcast projected onto giant screens, showing how propaganda and manipulation work in the TV age, to using actual transcripts of real conversations as part of the script. Still, the true impact of the Marcos regime never fully hits home until the last song, the folk-inflected “God Draws Straight,” which is performed by DJ Villarama, alone on stage with just a guitar. It records the protests that finally forced the Marcoses to flee the Philippines in 1986, as millions took to the streets in the People Power Revolution.

After all the noise and energy, the exuberance and the hubbub, this moment of quiet and reflection is not only affecting but shocking, as if we, the audience, have been complicit in the Marcoses’ rise. That complicity is drummed home further by Villarama’s acknowledgement that democracy is at risk today in America, as well as the Philippines, where Imelda’s son, Ferdinand “Bongbong” Marcos Jr., is now president, and where Imelda lives, unpunished, at the age of ninety-four.

In the end, however, Here Lies Love misses an important beat. The show should have ended with Villarama’s somber guitar. Instead, in a high-spirited finale, the music is once again pumped up loud, the cast come out shaking their hips and waving their arms, and the neon jumpsuits jump up and down, fixed grins in place. Everyone seems to be celebrating. But celebrating what? A good performance, maybe. The Marcoses, hopefully not.

And here lies the conundrum. Here Lies Love had a chance to reveal complex different layers, with the pageantry underpinned by grief, sadness and regret about a country led awry. Instead, it seems to be too scared to be serious in case the crowds get bored or in case they leave on a downer (newsflash: dictatorships are a bummer). It seems frightened, in fact, to ask the audience to do anything at all but dance.

As I stumbled back outside into the light, I couldn’t help but feel that this is a show that relies almost entirely on extravaganza and on novelty over depth. Ultimately, Here Lies Love is like the disco ball that spins above its audience: beautiful but fractured. And, at its core, hollow.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s September 2023 World edition.