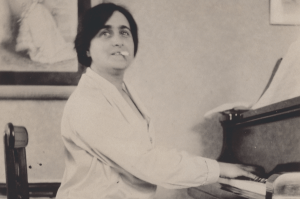

The niece of Jonny Kitagawa, founder of the Japanese talent agency Jonny & Associates, stepped down this week from her role as president, acknowledging the decades long sexual abuse of the company’s young clients by its founder (who died in 1999). In a typically Japanese scene of corporate self-abasement, Julie Keiko Fujishima apologized to the victims and pledged to dedicate the rest of her life to addressing the issue. It was a bravura performance but one that has been met with deep cynicism, at least from some in Japan.

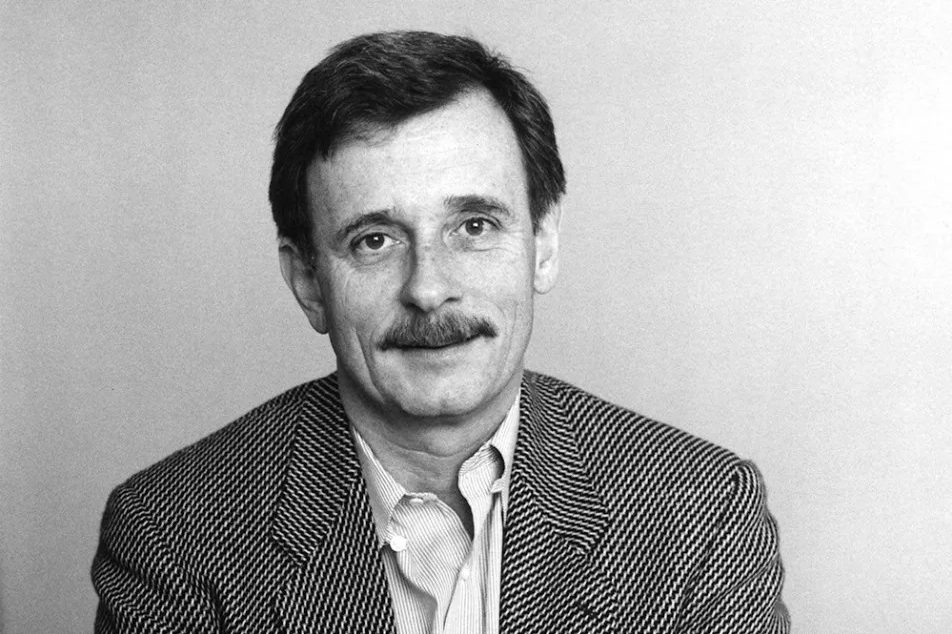

Jonny Kitagawa was the godfather of J-pop, an immensely powerful figure exercising dominion over the lives of his stable of young, often very young, male starlets (known in Japan as “talents” or “idols”). Kitagawa would micromanage their lives but in return was alleged to have expected sexual favors from vulnerable young boys often too cowed or innocent to either resist or even comprehend what was happening to them. Where Kitagawa lived became known as the “dormitory,” because so many young boys stayed over. Talent, numbering in the tens, has come forward with stories of abuse, and many believe this is just the beginning.

The Jonny scandal broke in 1999 in Shukan Bunshun, an independent weekly magazine. Jonny Kitagawa sued the magazine for libel but after four years the Supreme Court went against him. And then… not much happened. The trial was barely covered by the mainstream media and Kitagawa remained in control of his agency providing talents for 100 TV shows a week until his death sixteen years later. That event was covered by the media; it was front page news in every paper in Japan. There were tears and seemingly heartfelt eulogies.

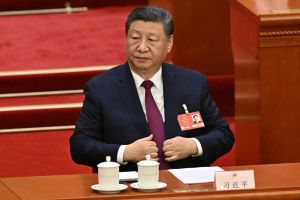

The story has simmered since then, but much of the heat has been generated outside Japan. The scandal came to international prominence as a result of a BBC documentary Predator: The Secret Scandal of J-Pop, which featured interviews with multiple Jonny’s clients who claimed to have been abused by Kitagawa. The Guinness Book of Records removed references to Kitagawa and the 232 number one singles he produced; just last month UN human rights experts criticized the company and called on the government to do more to investigate suspected abuse of male idols.

Perhaps because of this outside pressure, along with the rather more prominently covered Japanese #MeToo scandals and the formation of the Johnny’s Sexual Assault Victim’s association, the mainstream press in Japan finally begun to cover the story and things began to happen. There have been changes to Japan’s sexual abuse laws and the age of consent has been raised (from thirteen!). This was long overdue — one reason Jonny Kitagawa was never charged with a crime was that it wasn’t clear what crime he had committed.

The pressure has finally led to Julie Fujishima’s resignation — but what has really happened and how much has really changed in the company? Japanese corporate resignations are stage managed affairs (they even have specialized choreographers) where crocodile tears are shed. And has Fujishima even resigned? She was effectively ordered to go by a panel formed by the company in the wake of the scandal, but has said that she will remain as a “representative director.” She might still have considerable influence.

There is cynicism about the timing of the announcement too. It coincides suspiciously with the announcement by Japan Airlines that they would no longer be using Jonny’s artists. A major insurer, Tokio Marine & Nichido Fire Agency, was also reported to be considering terminating its contract. The “resignation” looks like a maneuver to take the heat out of the situation. A damage limitations job.

Will it have much effect on the J-pop industry? Probably not. Jonny’s remains robust and powerful. Its “talent” is still ubiquitous, it beams down with perfect faces from billboards and video screens all over Tokyo. The mostly female fans retain their unquestioning adoration for their pseudo-boyfriends, often traveling long distances and lining up just to take selfies in front of glossy posters of their idols when new ones are unveiled.

The internet has allowed the most famous performers, such as former Jonny’s clients SMAP, to bypass the once all-powerful agencies, to some extent, but the young talents remain firmly the property of the agencies, with everything they do, including even their relationships (forbidden) controlled. It remains a creepy, seedy business.

Japan’s hard-wired philosophy of endurance (“gaman”), where you are expected to put up with whatever indignities are visited upon you in the workplace, endures. That, along with a shame-based culture, and the complicity of vested interests (Jonny’s made and still makes money for many people) suggests that exploitation is likely to continue.

It is a business the fans show no signs of deserting. There is a striking lack of animus despite all we have learned. As one “huge” J-pop fan I spoke to about this issue put it: “It [Kitagawa’s abuse] was an open secret for a long time, especially among fans. But I don’t have any hard feelings for him.” It’s a surprisingly common attitude.

This article was originally published on The Spectator’s UK website.