While I was reading Most Delicious Poison, I visited a herbal garden in Spain which features the plants grown by the Nasrid rulers of Granada hundreds of years ago. They cultivated myrtle for its medicinal uses and jasmine for its fragrance. How did they know of myrtle’s properties? Some ancient ancestor must have figured it out. And that ancestor might be more ancient than we realize. Noah Whiteman explains that DNA from plants found in Neanderthals’ teeth tartar suggests even they were self-medicating with herbs. We have been entangled with the chemicals around us for as long as we have been human.

The author of this book, a professor of biology at Berkeley, takes us on a global trip through plants and their chemicals. It’s a kaleidoscope of facts and historical vignettes, both of how plant chemicals work, and how humans learned to harness some of them. He explains how scientists identified and were able to produce widely used drugs such as aspirin and codeine from their plant sources, and how cocaine made its way from leaves chewed in the Andean hills to a local anesthetic used in eye surgery and every partygoer’s nostrils in the 1970s.

But his focus is not just on the compounds we employ medicinally or recreationally. I had never really thought about the ink used in the eighteenth century. It was iron gall, derived from the tannins in oak galls made by tiny wasps. Small insect product was used to sign the Declaration of Independence — and the nature of tannins is what makes such old documents hard to preserve.

Forest-bathers actually gain from from the Valium-like calming effects of volatiles emitted by trees

We learn that montane voles’ breeding is affected by chemicals secreted in grass that basically act as a reproductive hormone, telling them it’s spring and turning on their fertility. Meanwhile, different plant chemicals tell them when winter is coming and to shut off ovulation. Other species’ breeding seems to be governed by day length, but the grass-chemical signal allows voles to squeeze out another litter if there’s an early thaw. Plants steer the behavior of animals more than we realize.

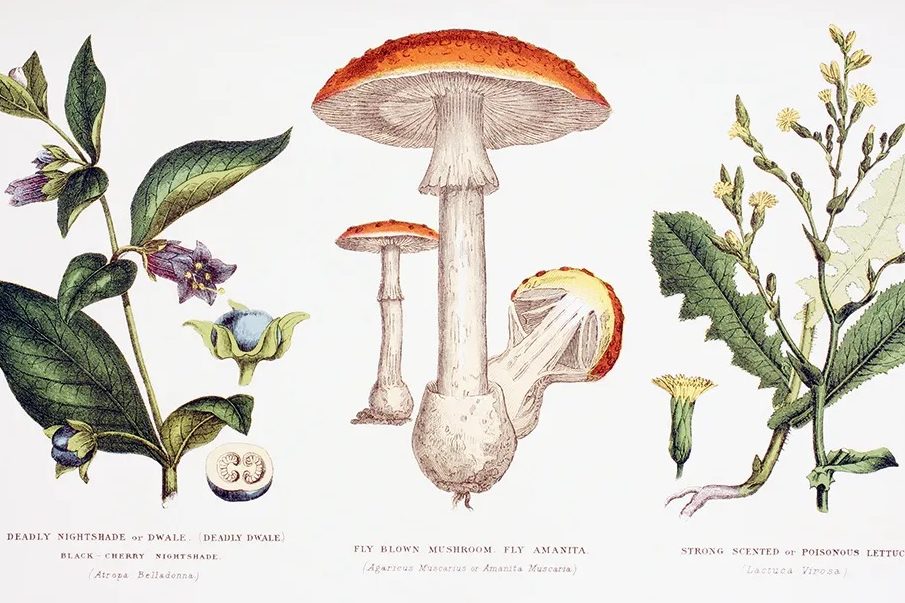

We are also attracted to plants for their appearance and scent, and have domesticated them for our enjoyment — which can be dangerous. Whiteman jokingly refers to “Houseplantaceae,” an eclectic group of mostly rainforest understory and desert plants often found in the living rooms, offices, hotel lobbies, shops and dorms and kitchens of our lives’. It’s easy to forget, when they come to us as home decor, that these plants are often toxic to ourselves or to our pets — as anyone who has had to make a panicked call to the vet while looking at a furry snout covered in pollen will know. (The metabolisms of carnivores versus omnivores are why dogs and cats are poisoned by so many plants that are harmless to us. Our systems are more ready to handle plant chemicals.)

Plants in nature can benefit us in ways we don’t fully appreciate. The Japanese custom of forest-bathing (shinrin-yoku) perhaps isn’t just about being somewhere peaceful. Participants are actually gaining from the Valium-like calming effects of volatiles emitted by trees. The subject is still being studied. But throughout, Whiteman reminds us: “Nature’s pharmacopoeia was not invented for us… There is no design with us in mind and no guarantee that the good will outweigh the bad.” We came to use these toxins or medicines over centuries of trial and error.

I imagine that Whiteman is an engaging teacher for undergraduates, as he manages to explain the chemical process even as I was having to cast my mind back to high school biology for how all this stuff works. Like balancing the dose of a drug, he goes just to the edge of “too technical” and brings it back to comprehensible for the non-scientist.

After reading this book, I ordered a filter coffee machine, something I haven’t owned in years. According to Whiteman, coffee produced by other methods (French press, espresso) contains more toxic compounds. Filtered offers more of the benefits of caffeine without the drawbacks. Beyond actionable tips, his small facts range from the useful — “just by eating a lot of plant-based foods, for example, we can attain levels of salicylic acid on a par with people following a daily low-dose aspirin regimen” — to the truly bizarre — that cicadas affected by psilocybin “become oversexed zombies even after their genitalia fall off.”

Insect orgy chaos aside, what Whiteman makes clear is that while we may have harnessed some of the useful chemicals from nature, there is still much that we need to learn.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply