When this newsletter launched in June, it opened with my exclusive report on the disturbing nature of the New York Times’s kids section. Across a handful of issues, which are sent out monthly and tucked into the Sunday edition of the NYT, the NYT for Kids encouraged children to explore their gender identity in online chatrooms, cheered on a child drag queen who had money thrown at him by grown men, insisted that “gender-affirming care” for children is totally safe and saves lives and instructed children to ignore adults who reject the left-wing propaganda in its pages.

I’ve still been reading the New York Times for Kids every month and am happy to share that subsequent issues following my report were mostly free of agitprop… until now.

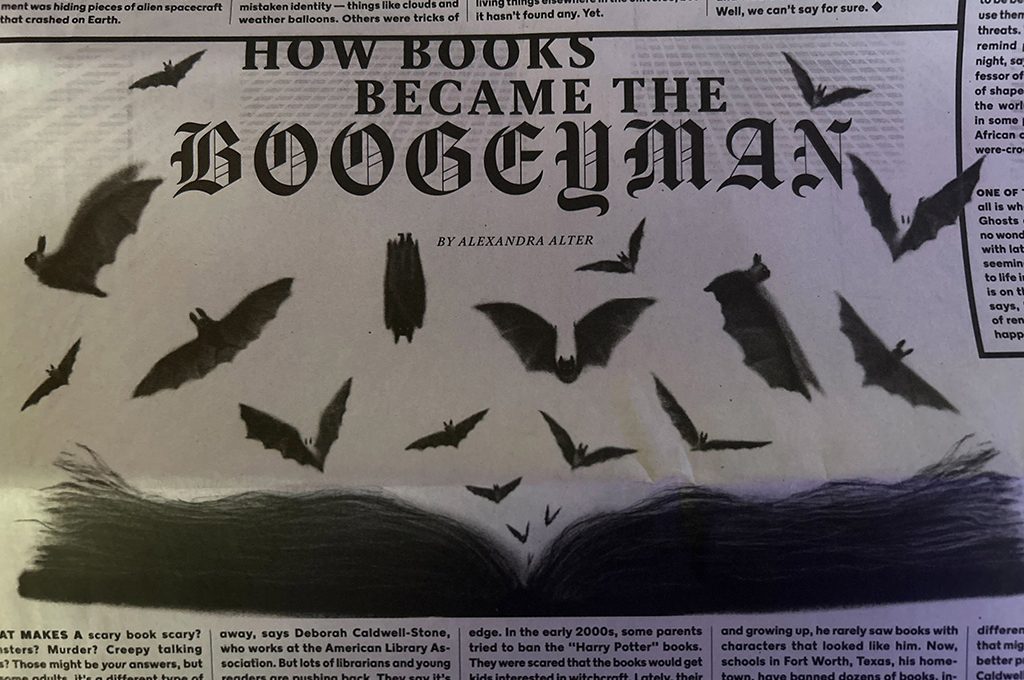

A couple of days before Halloween, the NYT for Kids sent out “The Unknown Issue.” After opening the cover, kids are greeted with an article title “How Books Became the Boogeyman,” authored by New York Times publishing reporter Alexandra Alter.

“What makes a scary book scary? Monsters? Murder? Creepy talking dolls?” Alter wonders. “Those might be your answers, but for some adults, it’s a different type of book that gives them nightmares: the ones about racism, gender and other sensitive subjects.”

The article goes on to compare modern book bans to the witchcraft panic over Harry Potter books in the late 1990s and early 2000s.

The real reasons certain books are being challenged in school and public libraries, of course, is not merely because they contain “sensitive subjects,” but because they contain overt racism against white people or sexually explicit content. In multiple viral videos, parents are seen reading the contents of books available in school libraries at local school board meetings; school board members respond by protesting that the material is not suitable for young audiences that may be watching the proceedings. How ironic. Stacy Langton, one of those moms, held up the contents of Lawn Boy and Gender Queer — graphic novels containing descriptions of oral sex and cartoons depicting minors engaged in sex acts — at a meeting in Fairfax County but was censored.

Other books that were available in school libraries included Let’s Talk About It, a book ostensibly about sex and puberty that shows images of “women” with penises and “men” with vaginas, as well as instructions on how to use butt plugs and research “kinks” and “fantasies.” Another oft-cited book by the parental rights movement was This Book Is Gay, which features the sentence “Oral sex is popping another dude’s peen in your mouth” and has a glossary of terms related to poop fetishes and sex toys.

Instead of acknowledging that the list of most-challenged books distributed by the American Library Association includes objectively inappropriate content for children, the NYT for Kids chose to list as examples some slightly less objectionable books.

“Lately, their boogeymen are books about more serious topics. For example, books on banned lists include The Hate U Give, which talks about the Black Lives Matter movement, and It’s Perfectly Normal, which discusses puberty and body changes,” Alter writes.

The Hate U Give, a novel inspired by the Black Lives Matter movement, has reportedly been removed from some libraries over its use of profanity and concerns it props up false narratives that unarmed black men are at constant risk of being killed by police (check out some of Heather Mac Donald’s work on this for more information). The book casts as its martyr a young black man who mouths off to police and resists their orders, escalating a simple traffic stop to a tense showdown. He is shot when he decides to reach for a hairbrush inside the car. I’m less jazzed about banning this book than the others mentioned, but I understand why a parent might not want their kid reading a very one-sided presentation of the debate about police brutality, which is fraught, emotional and filled with misleading statistics, without some guidance at home.

It’s Perfectly Normal includes full-color drawings of hetero- and homosexual intercourse and birth control methods and how to use them, plus explanations on how to masturbate. Perhaps another candidate for books that should only be provided to children with the explicit consent of their parents?

According to the NYT for Kids, though, parental concerns don’t outweigh the expertise of “black and queer” teenagers who have been groomed to believe their very existence is at stake if they can’t check out library books about gender transition surgery or strap-ons.

“[Banning books] doesn’t make Da’Taeveyon Daniels, sixteen, feel safe. He’s black and queer, and growing up, he rarely saw books with characters that looked like him,” the article explains. “‘My identity is being threatened,’ he says.”

The nonsense about book bans is not the only thing the NYT for Kids gets wrong in its October issue. The NYT fully credits modern Halloween celebrations to Samhain, an ancient Celtic pagan festival that marked the beginning of winter. While popular culture and media all agree with the false assertion that Catholics later started celebrating Halloween to try to sanitize Samhain, the truth is that Pope Gregory chose November 1 as All Saints’ Day to commemorate the date he designated a chapel in St. Peter’s Basilica to honor all Catholic saints and martyrs. As is customary with Catholic holidays, the evening prior to the feast day featured a special vigil. Hence why Halloween — a shortened version of “Allhallow-even,” a Scottish phrase meaning “All Holy Evening” — falls on October 31. Historians are split on whether Samhain even featured any of the traditions we now enjoy as part of our modern Halloween celebrations, such as trick-or-treating, costumes or creepy decorations.

It is curious that the NYT omitted the religious origins of the holiday entirely, even if it were only to mention that the name Halloween is derived from the Catholic holiday!

Sadly, nothing surprises me anymore from the mainstream media. The real shame is that they are now targeting children with their gibberish.

Leave a Reply