American Psycho was never supposed to be a hit. Bret Easton Ellis thought Glamorama would be his big seller, and Psycho was just an odd interlude; an experiment with form that mocked the disconnection, inanity and opulent obliviousness of America’s new, young, hyper-materialist upper crust. It was also a cloaked reflection of repressed homosexuality, written by a gay author who once dated a closeted financier.

It’s not even that violent. Most of it is just the interior monologue of this cold man listing the clothes and food and bad music that occupies his hollow mind. And it was intensely funny, but dryly, darkly so.

In short, it wasn’t an obvious literary smash. It only became one through a canceled publication by Simon & Schuster and accompanying media hysteria. It became the book “they won’t let you read.” So, people bought it.

When Mary Harron adapted it for the big screen, her great accomplishment was in highlighting just how funny the book was. Johnny Depp, Brad Pitt, Billy Crudup and Leonardo DiCaprio had all been interested in the title role, but (after studio hijinks) it went to Christian Bale, who perfectly captured Bateman’s icy emptiness. It was a moderate hit (earning $34.3 million on a $7 million production budget), and though it didn’t get Oscar nominations — which people oddly attribute to sexism against Harron, rather than the Academy’s conservative tastes conflicting with ironical chainsaw slaughter— it’s become iconic. Look at that subtle off-white coloring. The tasteful thickness of it. Oh my God. It even has a watermark.

And then, in 2006, Jesse Singer had an idea.

Act 4 Entertainment had never produced theater before, let alone been on Broadway; instead it made socially conscious documentaries. But Singer, who worked there as a producer, thought American Psycho could make a great musical.

It would have sex, violence, a fun Eighties setting, the best pop music of the era and a point to make about late-capitalist excess. He won over his boss, David Johnson, and the two men met up with Bret Easton Ellis at the Chateau Marmont. He gave them permission, but Los Angeles is a town where many ideas are pitched but rarely finished. And American Psycho: The Musical is a mighty improbable idea.

Singer pressed on. To start, he brought writer Roberto Aguirre-Sacasa (who wrote for Glee and eventually made Riverdale) to adapt the book, and two-time-Tony-winning composer Duncan Sheik, to write the music. Singer originally pitched it as a jukebox musical, but that didn’t interest Sheik (thank goodness). Instead, he created an almost-all-electronic synth-pop soundtrack on his 13” MacBook Pro, operated using the software Ableton — one of the first musicals to do so. Charlie Rosen (who now leads the 8-Bit Big Band) was the orchestrator on Broadway, but “It didn’t need to be orchestrated, or need anything additional, because it was all in the laptop,” he told me. “On the first day of rehearsal, Duncan walked in with a laptop in his hand, put it in front of me, and said ‘here’s the show.’”

Listening to the London cast recording, it doesn’t sound like any other musical. It’s the best, strangest club pop album the Eighties never produced. It’s meant to be raved to on molly. Rupert Goold, one of London’s most famous and adventurous theater directors, was already sold on directing American Psycho — but during their first meeting, Sheik passed him a pair of headphones and played the opening six tracks. Listening to them on repeat as he flew back to London, he’d fallen in love with them. “My daughter started listening to that album way before she was old enough for me to explain what was actually going on at the show” he told me. “She still listens to that score every day and she never saw the show, and she’s like thirteen.”

Though development started in the US, it soon felt that too little was happening and it was taking too long. As Goold recounts, after an underwhelming three-day development session in David Johnson’s LA office, “I said rather than doing another workshop, why don’t we just do a production in England? And they liked the idea.”

And so, in 2013, Act 4 and Headlong would bring American Psycho to London’s Almeida; a small non-profit theater, known for running ambitious shows for dedicated audiences. Goold would later become its artistic director.

As they entered September 2013, American Psycho was gearing up. They had their theater. They had the music. They had a great script. They had brought on the legendary choreographer Lynne Page, and set design was handled by the award-winning Es Devlin, who has worked with Kanye West, Beyoncé, the Weeknd and designed the closing ceremony for the London Olympics. Her Psycho set was a sleek white minimalist box, with video projections and two rotat- ing turntables on the floor, inspired by a cassette tape. Everything looked great; and tickets would almost sell out before the cast was announced.

There was only one missing component: their Patrick Bateman. Ben Walker had long been first choice, involved in workshops for the part since 2011, but he was unavailable for London, having signed on to Ron Howard’s In the Heart of the Sea. Matt Smith was the dream pick but he was doing Doctor Who. As they started casting in London, the list of actors was promising, but nothing quite worked. When they finally found the man for the role, he got immensely sick and had to drop out. And then, only three weeks out from rehearsals, Matt Smith gave Rupert a call.

On October 5, he shot his final scene for Doctor Who. On October 7, Smith started rehearsals for American Psycho, as London’s Patrick Bateman.

Compared with the book, Roberto’s script transformed its story into a sort of twisted romance — of the heartless Patrick and ditsy, upper-crust Evelyn — and though the same beats remained, they became on-stage musical numbers.

Bateman’s materialist obsession became the pop earworm/list-song “You Are What You Wear.” His erotic and physical fixations became the horny “Hardbody” and narcissistic “Morning Routine.” The book’s incessantly inane dinner conversations were distilled into the sarcastic “Oh Sri Lanka.” Page transformed the famous “Cards” scene into a spectacular athletic dance number, with dancers raising themselves up on glowing desks — legs arcing slowly up, as though played on a VHS in slow motion — “Killing Spree” made dance spectacle of slaughter.

Jesse Singer had offered to fly Bret Easton Ellis over to see the London show, but Ellis said he wouldn’t lie; if he didn’t like the show, he would say as much. They decided against the risk.

Thankfully, when previews started at the Almeida on December 3, 2013, it was a hit. At the open, the 325-seat theater was quiet and dark, with the cast standing amid the audience, wearing raincoats, and Smith’s tanned, ripped Bateman slowly rose into view on stage; and so it started. Critics loved it, crowds raved (some even turned up in costume) and the cast adored it.

“It’s quite a hard job to talk about because I just don’t have anything interesting to say about it other than I thought it was fucking great and I loved it, and I wish I was still in it,” actor Hugh Skinner, who played Luis, told me. And, had things gone differently, he may have.

Bar some extra enhancement money from David Johnson, the show covered its costs, and there was more than enough hype to sustain a West End run. However, theater owners wanted Smith in the role, and a commitment to do it for between four months and a year. Just off three years of Who, Smith wasn’t interested in being tied up for another long project, and so the West End dream died.

A year later, Smith told Goold over lunch that he regretted not doing a West End version. The producers would soon share his feeling.

Broadway is not cheap. Compared to the West End, it’s usually twice as expensive, and for Psycho, it would be even more. To make sure you don’t burn millions before an uninterested crowd, most shows do an off-Broadway run first. It lets them work out the kinks, and check you actually have an audience. American Psycho was going to follow this pattern, doing a run with Carol Rothman’s Second Stage. But, as plans progressed, it soon became clear that the finances didn’t make sense. Off Broadway runs always lose money, but this was going to be a lot; and so, when the veteran Broadway producer, Jeffrey Richards, gave them an opportunity to bring it straight to Broadway, they took it. And American Psycho went straight from the Almeida’s 325 seats to 1,079 seats at the Schoenfeld Theatre.

Many of the changes from London to Broadway were rather inconsequential; narrative tweaks, a different song for “Killing Time” and the removal of “Oh Sri Lanka.” After a four-hour meeting with the Broadway union they added two more live musicians, who had very little to do, and the ersatz accents in London were remedied with an American cast. On Broadway, they finally got their original Bateman, Ben Walker, who was dedicated to the role. Alongside him were two more notable cast members; comedienne Heléne Yorke as Evelyn, and the Tony-winning Broadway star Alice Ripley, as Patrick’s mother. To cast and the creative team, she was a loving, charming, hard worker. To the production staff, she was an abusive diva, who would throw lipstick and coat hangers, among other items.

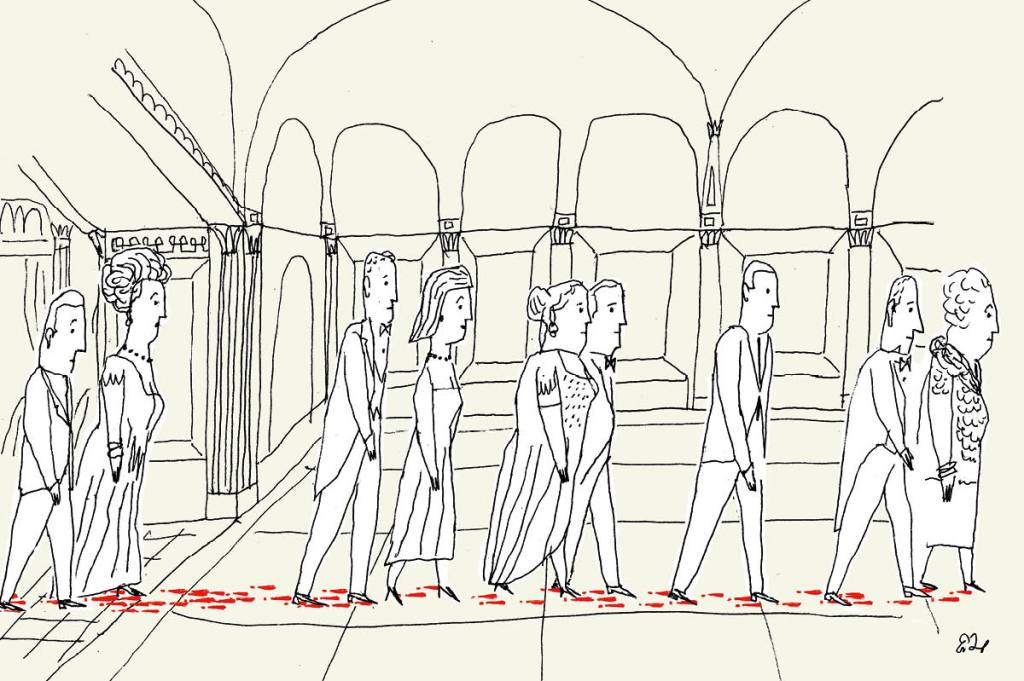

However, the biggest change from London was the blood. Given concerns about cleaning and wardrobe, the Almeida show had just used lighting and video projections, resulting in such a clean, metaphorical production. Warwick School brought its students to see it on a school trip. On Broadway, though, there were squibs and blood cannons and a giant shower curtain to protect the audience as Bateman took the ax to Paul Owen. A whole new dance sequence called “The Rat King” was added, which ended with giant pile of bloodied, tangled bodies. Music supervisor David Shrubsole told me the new song “Requiem” “was purely written to cover cleaning up the blood.”

During rehearsals, the crew loaded one of the blood cannons with water to see how bad it would be if they went off while the curtain was up. The water hit the theater’s back wall. Thankfully, the worst incident was the curtain not quite sealing in time, letting a small smatter of fake blood hit the feet of the front row, marking a Louis Vuitton handbag. The incident landed in Page Six.

When the show opened on April 21, 2016, the cast and crew were extremely proud of what they had produced; their audience would include Bryan Cranston, Calvin Klein, Phil Collins (appropriately enough), Anna Wintour, Bradley Cooper, Huey Lewis (also appropriately) and many more stars. Speaking with the cast, producers and creative team, there is an overwhelming, constant love for the people they worked with and the musical they produced; a truly bold, dramatic production that pushed the boundaries of what Broadway could do. It was a spectacle.

Yet it would close after just fifty-four shows, as an infamous Broadway bomb.

Rumors and reports would vary about how much it lost, with Bret Easton Ellis writing in his 2019 essay collection, White, that it had lost $14 million. This is likely the total production cost of all versions of the show, from inception, to Almeida, to Broadway, with total losses closer to $9 million. Insiders confirmed to me the Broadway show had a capitalization of $8.8 million (with Act 4 and Jeffrey Richards each controlling half of this), fixed weekly running costs of roughly $500,000, and a total gross of $5.63 million. Merchandising revenue was negligible and though the theater bar overperformed, that all went to the theater.

The red flags were there from the start. It was a show on Broadway that couldn’t bring in families or anyone under eighteen, and it wouldn’t appeal to tourists or much of the traditional Broadway crowd (AKA older women of means). After Goold saw the opening performance, he was convinced it was a great show, but it would need strong word of mouth and good reviews to get there. And soon after, Ben Brantley’s New York Times review dropped.

Though he had mildly praised the London show, noting points for improvement, his Broadway review was scathing. To Brantley, it was a spectacle of bodies but without being very sexy or scary. The Almeida’s focus on video projections and lighting made the show a minimalist, abstract metaphor; but by adding gushers of blood, the Broadway show lost that style, and drew attention to the now unrealistically simple set. “The Broadway production was kind of stuck between metaphor and literalism,” he told me.

Similarly, when audiences laughed at specific lines, some actors would lean in, playing up their humor (namely, references to items of Eighties nostalgia). To some, this helped let the crowd know that yes, this is a comedy. To others, it just undermined the dry wit of the text. Brantley thought it was condescendingly nostalgic.

The failure of Psycho was overdetermined. It was opening in April, when box office earnings are usually swollen by school trips, none of whom could see American Psycho. It was in an immensely competitive season, going up against Waitress, School of Rock and a little show — which got most of the attention and ticket dollars — called Hamilton. This played out at the Tony Awards too, where it was snubbed for Best Original Score, Best Musical and — most scandalously — Best Actor for Ben Walker as Bateman. And rumors spread as to why.

Namely, that this was fallout for Walker’s scandalously abrupt marriage to Meryl Streep’s daughter, Mamie Gummer, who he left after falling for Scarlett Johansson, and a concern that voting for Walker would put you on the wrong side of the legendary Streep (who sources confirmed still has no warm feelings for Walker).

But this is a stretch. As James Forbes Sheehan, an associate producer on Psycho, told me, “Ben Walker was a journeyman actor playing an unlikable character in a new musical; Zachary Levi [who was nominated for She Loves Me] was a TV star showing a new side of himself in a musical revival that was universally beloved. Do the math!”

Though Psycho had many factors working against it, perhaps it can be distilled to this; it wasn’t Broadway material. It was inherently risqué, without a hero to root for; you didn’t know quite how to feel on leaving it. It was bolder than Broadway could stomach, and though the show did have a passionate fan base, its fans were young, and young audiences buy cheap seats. This meant that even on weeks with almost 90 percent occupancy the show barely broke even; average ticket prices rarely topped $80 (their internal target was $100). At the end of May, when notice was given to the cast, only 68 percent of seats were sold. In those showings, there were more empty seats than the entire audience of the Almeida. It closed on June 5. Much to the cast’s frustration, there is no original Broadway cast recording. The only way to watch it (aside from the YouTube bootleg) is an archival recording at the New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. This recording was paid out of pocket by — as the library’s records put it — an “anonymous donor.” That donor was producer David Johnson.

Tragically, in the final week, just as it was about to close, it felt how it should been the whole time; with raving crowds who didn’t just love the sex and blood, but ran their hand through the pooling blood on the stage, and wished there had been a splatter zone to get soaked in the front row (which was briefly considered). “It felt like a rock concert,” Jesse Singer told me. “I remember looking around and thinking, why are we doing this in a proscenium? Why do we even have seats?” And then, eight performances later, it was gone.

The following Sunday, Lynne Page texted Rupert Goold, “How are you? You alright?”

“You know, not really,” he replied.

“I was really upset about it, more upset about any other show closing really,” Page told me. “I wept. Maybe one shouldn’t feel that way, because it’s ultimately just a piece of theater, but it’s not just a piece of theater. We put 100 percent of our heart and soul into it. It was grief.”

Seeing the New York show in 2015, Bret Easton Ellis said “It’s kind of like remarkable. In some ways, this is my favorite version of the material.”

When I emailed him for this piece, Ellis replied, “In the States it was a flop losing $14 million and I had nothing to do with it. Why would I want to talk to anyone about this?”

“I have no desire to talk about this — it is not personal at all. I have zip.”

American Psycho ends with the capitalized “THIS IS NOT AN EXIT.” And though the musical was dead on Broadway, that wasn’t the end. It had a successful 2019 run in Sydney, Australia, was adapted for an episode of Riverdale and there are many dreams for how it could be restaged.

Goold would like to bring it back to the West End — or better yet, make a film of it. Brantley thought it could work quite well as an opera, but “the musical for me probably works best at its most ragged.” Hugh Skinner wants a ten-year anniversary concert.

In 2025, American Psycho will return to New York; this time, as an atmospheric musical (akin to Here Lies Love and the work of Punchdrunk) in a Brooklyn warehouse. The warehouse currently just has dirt in it, and some assorted boxes stored at the back. When it opens, it’ll be the coked-up synth club of Bateman’s dreams.

In fall 2023 a Chicago production of the show will have wrapped up in the Chopin Theater. Director Van Barham had embraced the gayness and camp of the novel (using glitter and confetti for blood during “Killing Spree”), and there was an intimacy to the show, with 100-or-so guests being so close to the stage they could reach out and touch the cast.

Years ago, in the audience of the final performance of the Broadway production there was a sixteen-year-old girl, Caleigh Pan-Kita. Her mother’s friend was an investor and wrangled her a ticket; and as the cast took their final bow, Caleigh’s view of musical theater had changed. “I’ve never seen like people who loved theater more than those people performing on stage,” she told me. “They were like, ‘This is what I was meant to do’ and this is the last time I’m ever going to perform this show’ and it literally changed my life.”

This fall, Caleigh will take her final bow as Evelyn in the current Chicago production. And there, with that audience, in the year 2023, improbably as always, American Psycho: The Musical proved a success.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s December 2023 World edition.

Leave a Reply