The view from my top floor room at the Steigenberger Hotel de Saxe looked out at the great dome of the Frauenkirche. It’s a huge Baroque church in the center of Dresden; I first saw the building on foot, when failing to find a local restaurant on my first night there. I turned a corner to see it towering above me. It looks like it’s always been there, but the original was destroyed in 1945, under the infamous British firebombing, and reconstruction only finished in 2005. I was eventually directed to the restaurant, past the Oktoberfest stands that began sprouting up during my visit in late September.

However beautiful the town, I was not here for “Florence on the Elbe” and its grand buildings, but for smaller, more delicate wonders from a nearby town. And so, at 8 a.m. on a crisp Thursday, I took a car along the same route that Ferdinand Adolph Lange had traveled almost 180 years before, when he founded the company that arranged my commute, A. Lange & Söhne. My destination was Glashütte.

Twenty miles south of Dresden, through gently winding roads, past farms and cottages, in a valley carved by the Müglitz and Priessnitz rivers, this little town is home to 1,600 residents, one museum, one chicken restaurant and some of the best watchmaking in the world. There are currently nine watch companies operating here — Moritz Grossmann, Tutima, Wempe Glashütte, Union Glashütte, C. H. Wolf, Bruno Söhnle, Glashütte Original, and the two brands I was visiting, A. Lange & Söhne and Nomos Glashütte. If it says a watch was “made in Glashütte,” it means something. By law, you can only apply the label if 50 percent of a watch’s added value came from Glashütte. You can also tell a watch is from Glashütte by its signature cornflower blue screws and three-quarter plate ribbing.

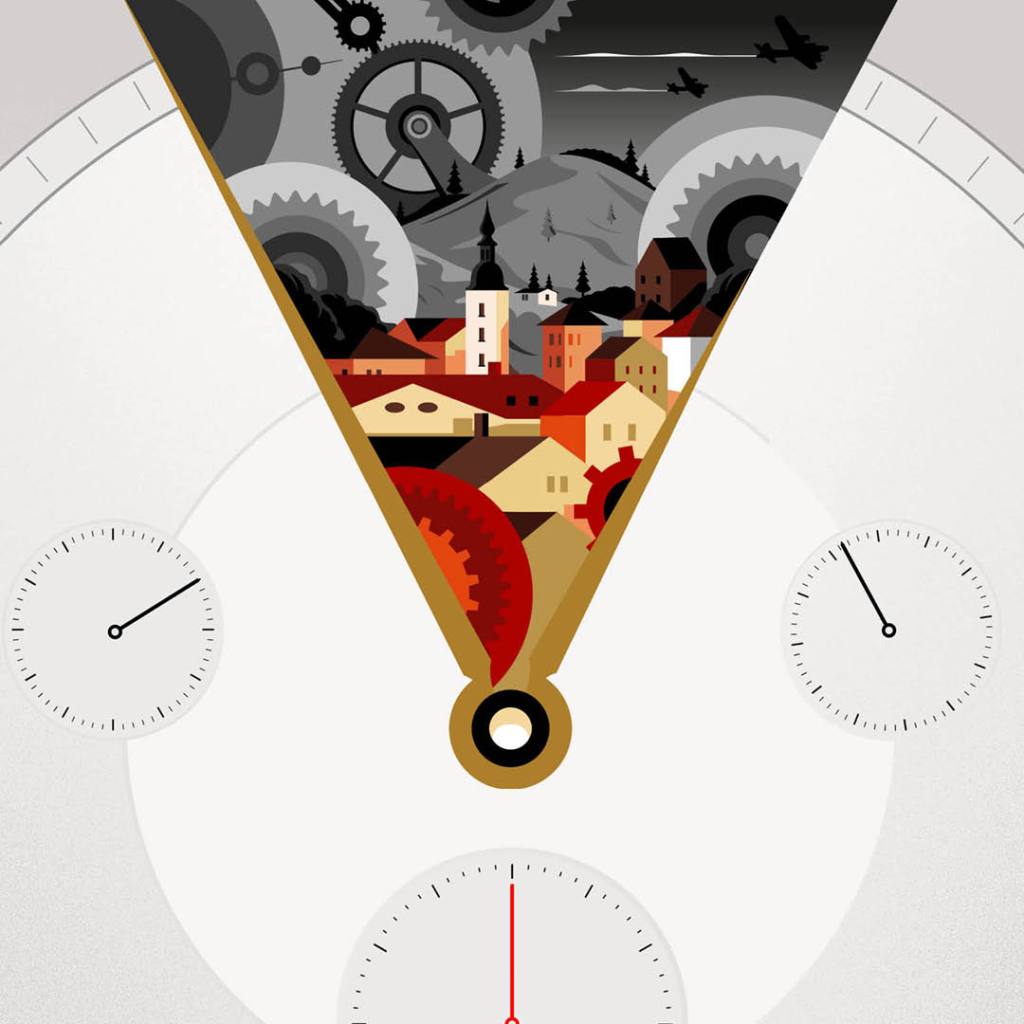

It’s pretty, small, surrounded by green and gently quiet. But the hands of time have not always been kind to Glashütte.

Germany was once renowned for its timepieces, until the Thirty Years’ War turned much of the country, its economy and people to dust. During the eighteenth century, Saxon leaders tried to resurrect the local craft, with Frederick Augustus I bringing watchmakers from England, France and Switzerland to Dresden, only for the city soon to be burnt and battered by riots, the Seven Years’ War and various episodes of Prussian rule. It would only truly burst back to life in the nineteenth century, as capital of Napoleon’s new Kingdom of Saxony, and the local government and elites wanted to restore the surrounding areas too.

The Erzgebirge (Ore Mountain) region, where Glashütte lies, was economically devastated by the vast seventeenth-century glut of Mexican silver, which collapsed its prices. With the silver market gone, slowly crumbling under poverty, disease and fire, Glashütte needed a new purpose; and with the help of a Saxon government scheme and fifteen local apprentices, F.A. Lange brought it. He founded his watch company there in 1845 — and by the time the German School of Watchmaking opened its doors in 1878, there were many other brands in town.

After World War One decimated the German population, and the post-war depression did the same to the country’s economy, nobody was buying watches. Glashütte’s unemployment hit 85 percent in 1926, and the banks of the Müglitz broke the following July, unleashing a flood that destroyed much of the town and killed more than 150 of its residents. Military contracts from the new Nazi government improved business in the 1930s, but during the war, Glashütte became the site of an Arbeitslager, or forced labor camp, and its watches — including those from A. Lange & Söhne — became products of this slave labor. The town was then bombed. When the war ended, its watch industry disappeared behind the Iron Curtain. Machines and tools were shipped to the USSR, and the communist German Democratic Republic consolidated all its watch brands into a government-run conglomerate. The Soviet watches worked — they kept time — but lacked soul.

In 1989, the Berlin Wall fell. Communism was dead. And Glashütte’s watchmaking came back.

At their campus, I popped my phones and camera into a locker, trading for a notebook and pencil, and was offered some coffee. So began my tour of one of A. Lange & Söhne’s six buildings.

To those who don’t interest themselves in timekeeping, A. Lange & Sohne is not a big name. They’re not flashy, influencers don’t flex about “icing-out” their Zeitwerk, thankfully, and their brand doesn’t fill rap lyrics like Rolex, Patek Phillipe, Audemars Piguet, Hublot or Richard Mille.

However, industry insiders working in parts manufacturing are unreserved in their praise. Put simply: the precision of Lange far outstrips its competitors’, even at a similar price point. “A lot of the Patek hype is just the name,” one watch industry person told me, recounting being unimpressed by the standards demanded for a particular piece. “Lange sets the bar.” And each part is so small, and requires such precision, that no machine will do. Though it’s monitored by advanced tools, everything at Lange is done by hand.

The beryllium alloy balance spring — patented by Richard Lange in 1930 — can be under a hundredth of a millimeter thick, made to a manufacturing tolerance of one 10,000th of a millimeter. Each link on the fusée-and-chain transmission — essentially a minute bicycle chain, keeping the tourbillon (in short, a complicated device that helps in accuracy) perfectly precise — is so small that assembly requires tweezers, loupe and an immensely steady hand (yet the final product could suspend two kilograms’ weight). Each watch comes with an engraved balance cock — a floral-pattern signature, carved in gold — and the pattern is not sketched or planned beforehand. Yet, moving in minute, perfect curves, the engraver fits each groove into the last, making a perfect final pattern, all on a piece of metal smaller than a fingernail. When you’re aiming for perfection, even the tiniest screw has to be perfectly polished, even when it’s so small you can barely tell it’s a screw with the naked eye.

A Lange 1, one of their flagship models, has more than 100 different oil spots in its construction and six different oils needed to lubricate it — and that’s without some of the possible exotic complications, like jumping seconds, split-second chronographs or minute-repeaters, which chirp the time when you press a button. The Lange 1 was one of the four initial relaunch models unveiled by Walter Lange in 1994. He had fled Glashütte in 1948, when the communists ordered him to work in a uranium mine — a death sentence. In 1990, in his sixties, he took back his family’s legacy and restarted his great-grandfather’s brand.

When I was first getting into watches, I wasn’t intrigued by the Lange 1. In photos, it didn’t work. It didn’t look modern or futuristic, and it was also asymmetrical, with minutes and hours in one large subdial, seconds in a small one to the side. But when I held the black-dial Lange 1 Perpetual Calendar in my hand, it was perfectly balanced. Its date window — which I once thought oversized and blocky — is an homage to the five-minute clock of Dresden’s Semperoper opera house. That revolutionary timepiece was designed by Johann Christian Friedrich Gutkaes, when Ferdinand Lange was his apprentice.

The Lange 1 — like the company’s Zeitwerk Lumen Phantom, its 1815 Rattrapante, and the Richard Lange “Jumping Seconds” — is perfection encased in platinum. I would kill to own one and, frankly, would need to. The website reads “Price on Request,” because if you need to ask, you don’t have the roughly six figures needed to buy one. Lange also has to want to sell you one. Rolex makes about a million watches a year, and Patek Phillipe produces roughly 60,000; Lange restrains production to between 5,000 and 6,000. You can’t do what Lange does at much greater scale.

Were it just for Lange, Glashütte wouldn’t be what it is today. Even with their apprenticeship program — which has graduated 230 watchmakers, most of whom started as teens from the local area — Lange makes too few watches at too high a price to sustain a local industry and a whole town. Rather, it’s Lange’s neighbors who’ve brought Glashütte to the world stage, pulling in young customers by offering incredible craftsmanship at more moderate prices. The watch brand Glashütte Original offers this, with most of their watches ranging from $5,000 to $15,000, but they’re owned by Swatch, the massive watch conglomerate, and though neighboring brand Bruno Söhnle watches are often under $1,000, their designs are generic and run on outsourced Sellita or quartz movements.

But the brand Nomos is pure Glashütte. They’re still family owned, their watches are up to 95 percent made in Glashütte and — since 2014 — they exclusively use their own fully in-house movements, powered by their own in-house escapement. Nomos’s Swing System took seven years and €11 million to develop but now Nomos operates completely independent of Swiss manufacturers. Despite all this, their watches start at $1,380 — and most are under $5,000.

Nomos is not only the biggest producer of mechanical watches in Germany; it kicked off this new era for Glashütte. Roland Schwertner founded the brand in 1990, only a few months after the Wall fell, and the first line, of four watches, was released in 1992. The Tangente remains their best-selling watch. Roland and his co-workers started the company in an apartment before moving to their old train-station headquarters.

Compared with the classical intricacy of watches from A. Lange & Söhne, Nomos designs come from Bauhaus principles. They use clean lines, subtle text and detail, and color is always at service of function to help clearly tell you the time. The subtle grooves on the second subdial help visually separate it from the minutes and hours, as does the popping contrast color on its hand. Despite setting off the “minimalist” watch trend, they are anything but boring. Their youthful Club Campus is a canvas for interesting colors, sold in electric green, bright tangerine, vivid blue, cream coral and rich purple with light blue accents. Rather than just show the date in a window, as is conventional, their Neomatic Update watches use two bright pill-shaped cut-outs, which circle the dial, and their Zürich World Time lists twenty-four cities on a disk behind the dial, which spins into place when you change time zone with the press of a pusher.

Nobody needs a watch. Your smartphone will tell the time more accurately than any you can buy. Besides, the most expensive, complicated watches usually live in glass cases, bought as investments or just because you can. In an era where watches are not needed to show the time, they’ve often just become a way to show you’re rich.

But that’s not what the best of watch culture is. It’s not about beautiful hotels and black limos and spending piles of cash. It’s not why Pete, who has worked at Lange for sixteen years, perfectly carving balance cocks, or the tattooed Mark, another worker, assembles those tiny bicycle chains, or the ladies in the hillside Nomos Chronometrie building — giggling as they try to avoid tour-group cameras — arrive at six in the morning to start assembling watches.

There was a young woman, roughly my own age, working in the Lange 1 division, named Mary. She grew up near the region. The watches that she builds, and trains others to build, could last hundreds of years given the right maintenance, telling the time for generations after we’re gone. I asked whether it feels special to make something that will so outlast her. “Yes. Yes, it really does,” she said. She had a proud smile.

At its best, a watch tells the time for its owner. It marks where you’ve been, what you’ve achieved, the dreams you had, and the legacy you want to leave. It’s the Timex you run a marathon in, the Breitling your father flew with, the Daytona your brother sailed with. A watch can freeze a memory and hold it in a little piece of beauty that you wear on your wrist.

It’s not about the money. As I walked around the Lange factory, I wore a Blok 33 on my wrist; a black, quartz children’s watch, from a small brand. It’s not expensive, but it’s cool, and has lovely design details, and I love it for the memories of travel that I make with it. It makes me smile, just as it did some of the folks in Lange, who paused in assembling an $89,000 Zeitwerk to take a look.

I still default to checking the time on my phone, and I get distracted in the meaninglessness of the mundane daily — but every morning, as I wind up the little pink watch on my wrist, I step away from that all. It’s a Nomos Club Campus with a chunky steel sports band. I bought it to mark my first year working full-time in journalism. It will return to the people who made it every five or six years for maintenance, and hopefully long outlive me. I hope to give it to my eventual first child, when they go off to pursue their life.

Through wars, floods, depressions, Nazi control, Soviet dreariness and the rise of quartz, Glashütte still ticks on; as does my little pink watch, born and made there, which carries my memory of visiting. And, carrying the spirit with which it was made, I wear it with pride.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s January 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply