When T.S. Eliot published “The Waste Land” in 1922, it was seen as a masterpiece of modernism. It was, but it was also a work steeped in cultural tradition. This was made apparent in the “Notes on The Waste Land” with which Eliot supplemented his poem. In them, he glossed its literary echoes — the Upanishads, Dante, Chaucer, Mallory, Shakespeare, etc.

Another master of the modern who came to his greatest flourishing between the world wars was P.G. Wodehouse. Though seven years older than Eliot, Wodehouse first achieved real fame at much the same time, after the publication of The Inimitable Jeeves in 1923. Like Eliot’s, his work’s modernity, making such innovative use of the main literary traditions of the West, would have been unimaginable in the 19th century. But Wodehouse produced no “Notes on Jeeves,” or on any of his oeuvre, to guide the potentially perplexed reader. Had he done so, he would have risked over-explaining, thus killing his main intended effect, which was to make people laugh.

Being funny requires artistry. It is a demanding craft now practiced by a skilled few, like dry stonewalling

For this reason, there is a strong case for maintaining a Wodehousian silence about the Master’s references; but I have decided that two arguments point the other way.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]The first is that many of his cultural allusions, wholly familiar to the English middle classes, especially English public schoolboys, from the 19th century to the 1980s, are now forgotten. They need rescuing, or rather, for scholars have ploughed this furrow, re-rescuing.

The second is that, in the twenty-first century, the word “comedy” tends to mean a left-wing person standing up to swear and shout against fossil fuels, Boris Johnson, “homophobia” and so on. In the twentieth century, by contrast, comedy involved being funny. That art now requires elucidation before it is, as Wodehouse might have put it, “one with Nineveh and Tyre, and spats.” Being funny requires artistry. It is a demanding craft practiced only by a skilled few, like dry stonewalling.

Samuel Johnson famously complained of the seventeenth-century Metaphysical Poets that, in their work, “the most heterogeneous ideas are yoked by violence together.” But what Wodehouse saw, as Johnson perhaps did not, was that such yokings can be funny. For his art, the joke of the yoke lay in the contrast between the epic, romantic, scriptural or classical sublimity of the original words from great literature and the invariably farcical situations he described.

In the case of Wodehouse’s best-known creations, the idle aristocrat Bertie and his valet Jeeves, the joke has an added layer. In the great tradition of master/servant comedy, Bertie is the damned fool and Jeeves the learned sage. Thus: “‘Childe Roland to the dark tower came, sir,’ said Jeeves, as we alighted, though what he meant I hadn’t an earthly.” That is a quotation from the fool in King Lear, and perhaps a nod to Robert Browning’s poem of that name. Bertie likes to repeat and apply such quotations, but he mangles them as he does so. He often believes that Jeeves himself invented them.

This deployment of the high style occurs in most Wodehouse, but Jeeves and Wooster display it most clearly. To illustrate this, I have used only one book, his novel, The Code of the Woosters, first published in 1938, and widely regarded as Wodehouse’s most successful full-length work. It concerns the troubles which ensue when Bertie is persuaded by his beloved Aunt Dahlia to steal a silver cow-creamer from the grim Sir Watkyn Bassett. Unusually for Wodehouse, the book also contains political satire. The vast and preposterous Roderick Spode, associate of Sir Watkyn, is the bullying leader of an extremist movement (this is the late 1930s, remember) called the Black Shorts.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

The opening page of The Code of the Woosters contains two literary references of the sort described.

The first immediately establishes the relationship between Jeeves and Wooster. Bertie is in bed with a hangover. He summons Jeeves under the impression that it is evening. Jeeves explains it is morning. “Are you sure?” asks Bertie, “It seems very dark outside.” “There is a fog, sir. If you will recollect, we are now in autumn — season of mists and mellow fruitfulness.” The quotation Jeeves deploys is from Keats’s “Ode to Autumn,” unattributed.

“Season of what?”

“Mists, sir, and mellow fruitfulness.” [Note the comic effect achieved by inserting the “sir” at just that point.]

“…Well, be that as it may, get me one of those bracers of yours, will you?”

Words from literature lurk in Bertie’s mind (if that is the right word for what he calls his ‘bean’)

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]

The second reference is Biblical. Wooster needs Jeeves’s bracer because of carousing the night before: “I had been dreaming that some bounder was driving spikes through my head — not just ordinary spikes, as used by Jael the wife of Heber, but red-hot ones.” In the Book of Judges (4:21), Jael slays Sisera who, as commander of King Jabin’s army, had been oppressing the Israelites, while he sleeps. According to chapter four, verse twenty-one, she “smote the nail into his temples and fastened it to the ground… So he died.”

By my count, The Code of the Wooster’s contains eighty-five such references, including some that are repeated and varied, such as “quills on the fretful porpentine” (Hamlet), or the frequent comparison of Bertie with the heroic Sydney Carton in Dickens’s A Tale of Two Cities. (“Who does Mr. Wooster remind me of, Jeeves?” “Sidney [sic] Carton, miss.”) Such invocations are mostly classical, Biblical (or from hymns) or literary. A few are proverbial with no known original, or references to historical legends, such as Isaac Newton exclaiming “Diamond, Diamond, thou little knowst what thou hast done,” when his dog — with whom Bertie ruefully compares himself — ate the notes of his scientific discoveries.

There may, of course, be allusions I have failed to detect. Some words sound like literary references but I cannot source them, such as the phrase “hoggish slumber,” much favored by Wodehouse. It sounds Shakespearean, but isn’t.

The actual code of the Woosters, the motto by which Bertie says his family lives, is “Never let a pal down.” The literary code of the Woosters is much more complicated.

Decoding Wodehouse’s quotations, echoes and allusions by author or other source, I find as follows:

The Bible (always the Authorized Version): fifteen references (four Psalms, two passages from Matthew’s Gospel, one from Luke’s; two from Judges; and one from Proverbs, Job, Isaiah, Exodus, Daniel and the first Epistle of Peter); plus three hymns.

Shakespeare: fourteen (from Sonnet 33, Twelfth Night, Macbeth, Hamlet, King Lear and The Tempest).

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Keats: three.

Dickens: three.

Shelley: two.

Byron: two.

Tennyson: two.

Longfellow: two.

Kipling: two.

Robert Browning: two.

;768:[300×250,336×280,320×100];0:[300×250,320×100,320×50]”]Matthew Arnold: two.

Troubadour poets: two.

Juvenal: two.

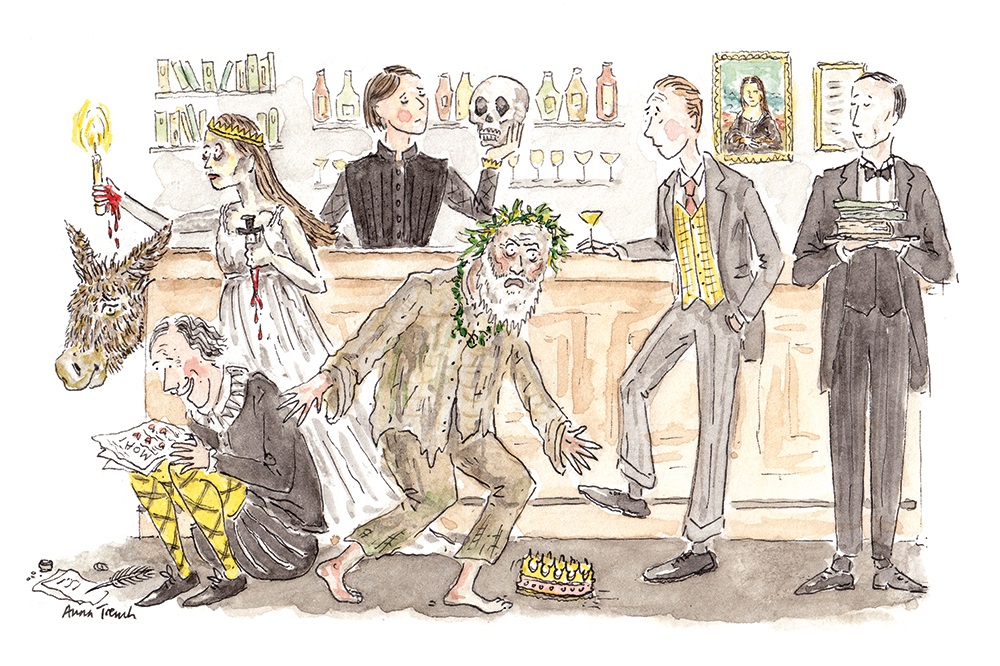

And one reference each to Burns, Edgar Allen Poe, Goldsmith, Homer, W.E. Henley, Leigh Hunt, Marlowe, Baroness Orczy and Felicia Hemans. Then there are mentions of, rather than quotations from, Damocles, Archimedes (who comes up a lot, always in his bath), “Venus from the foam,” the Mona Lisa and the painting “The Soul’s Awakening” by James Sant RA; plus remarks on the nature of Greek tragedy.

This range of reference and the relative numbers of mentions almost perfectly reflect the hierarchy of knowledge that would have been imparted to children, particularly boys, in all good schools.

So does Wodehouse’s choice of quotations. He almost always picks the passages which were best-known and recited young. Thus the words of Byron which appear are nothing sophisticated or sensual from Don Juan, but the most famous line from “The Destruction of Sennacherib:” “The Assyrian came down like the wolf on the fold.” The presence of Felicia Hemans is attributable to the only lines she wrote which everyone knew (from her poem “Casabianca”): “The boy stood on the burning deck when all but he had fled.” Baroness Orczy’s work is cited (not by name) because Bertie recalls a historical novel “about a Buck or Beau or some such cove who, when it became necessary to put people where they belonged, was in the habit of laughing down from lazy eyelids and flicking a speck of dust from the irreproachable Mechlin lace at his wrists.” Bertie claims he “had had excellent results from modeling myself on this bird.”

Most readers were sufficiently familiar with the story to work out that he was talking about The Scarlet Pimpernel. But part of the joke was also that dimmer readers would resemble Bertie in only half-remembering what they had once heard, and would enjoy laughing at themselves about that.

Bertie is, in a way, much affected by literature. Its words lurk in his mind (if that is the right word for what he calls his “bean”), having been put there either by his school or by Jeeves and almost never by reading the book in question (though he did win the Scripture Prize at prep school — “a handsomely bound copy of a devotional work whose name has escaped me”).

The words often surface, but confusedly. When Jeeves asks his master if he plans to obey Aunt Dahlia and steal the cow-creamer, Bertie answers: “That is the problem which is torturing me, Jeeves. I can’t make up my mind. You remember that fellow you’ve mentioned to me once or twice, who let something wait on something? You know who I mean — the cat chap.” “Macbeth, sir, a character in a play of that name by the late William Shakespeare. He was described as letting ‘I dare not’ wait upon ‘I would,’ like the poor cat in the adage.” (See Macbeth, Act I, Scene VII, Lady Macbeth speaking.)

Once lodged in Bertie’s bean, an image tends to recur, slightly modified. He later plucks up his courage to enter the small drawing room of Sir Watkyn’s country house and remove the silver cow from its case. “My frame of mind,” he records, “was more or less that of a cat in an adage.” He fishes out the cow-creamer, but is surprised by Roderick Spode, whose shotgun was “pointing in a negligent sort of way at my third waistcoat button.” Later still in the book, Bertie’s goofy friend Gussie Fink-Nottle is found “doing the old cat-in-an-adage stuff.”

Not every image needed Jeevesian elucidation, however. Thus the village policeman, Constable Oates, is “prowling in the rain like the troops of Midian.” Readers required no reminding that these Midianites are to be found in J.M. Neale’s Victorian version of the old hymn by St. Andrew of Crete, “Christian, does thou see them.” Similarly, when Bertie declares, apropos of the ruthless Stiffy Byng, “Kipling was right. D. than the m,” he knew this was all he needed for readers to recognize the line “The female of her species is more deadly than the male.”

I come back to Eliot, and to the Metaphysical Poets. In an essay published in 1921, the former praised the latter as the last writers who did not suffer from the “dissociation of sensibility” characteristic of more modern times. The Metaphysicals had the gift, he wrote, of “constantly amalgamating disparate experience.” I would argue that Wodehouse had that gift, though in quite a different form and for entirely non-metaphysical purposes. That is one of the reasons why he is funny, comedy being the chief register of the disparate. A world which has now almost passed loved him for it.

I would also argue that he bestowed that gift upon Bertie Wooster. A well-equipped “poet’s mind,” wrote Eliot, “is constantly amalgamating disparate experiences.” In Wodehouse’s hands, this is true not only of poets but of his most famous fathead.

As I said, The Code of the Woosters begins with two images drawn from great literature. It ends with two more.

Having, thanks to Jeeves, defeated Spode and Sir Watkyn, and secured the cow-creamer, Bertie retires to bed, switches off the light and reflects: “Jeeves was right, I felt. The snail was on the wing and the lark on the thorn — or, rather, the other way round — and God was in His heaven and all was right with the world.” That is Bertie’s version of “Pippa Passes,” by Browning.

He ends with an image drowsily drawn from his memory: “…presently the eyes closed, the muscles relaxed, the breathing became soft and regular, and sleep, which does something which has slipped my mind to the something sleeve of care, poured over in a healing wave.” The reference is from Macbeth, Act II, scene ii, in which sleep “knits up the raveled sleeve of care.” Thus are the successful pinching of a cow-creamer and a bloody Shakespearean murder committed out of power hunger “yoked by violence together.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply