It is early in the morning on the “day of infamy,” Sunday, December 7, 1941. Two hundred and fifty miles north of Hawaii, six Japanese aircraft carriers are preparing to launch more than 350 aircraft in a surprise attack on the United States Pacific Fleet at Pearl Harbor.

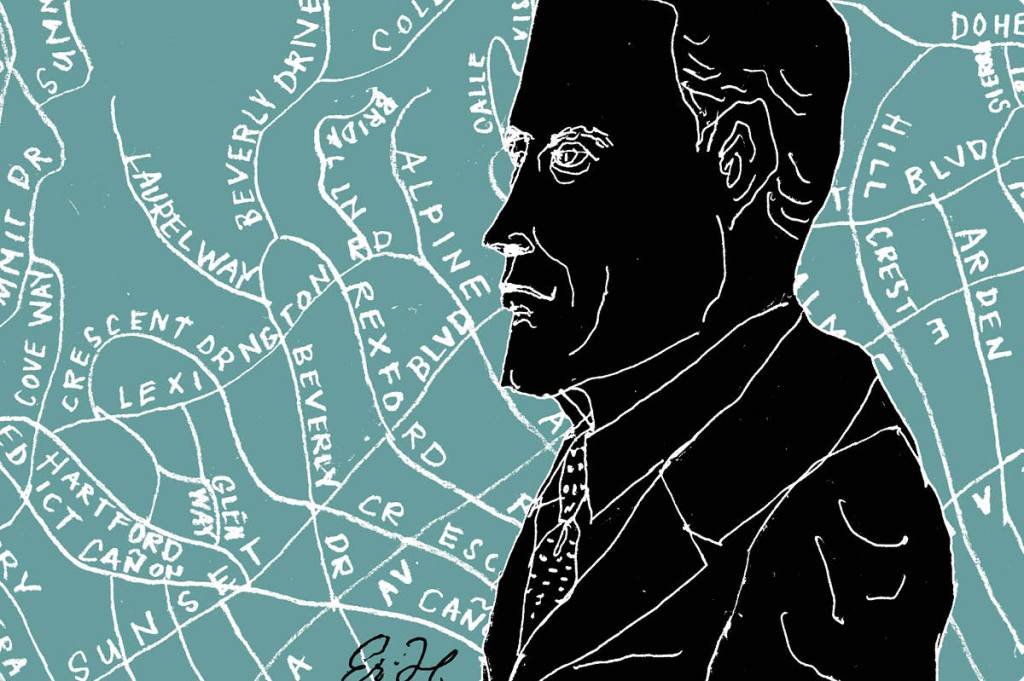

The fleet’s commander-in-chief, Admiral Husband E. Kimmel, had told a reporter the day before that the Japanese would be “damned fools” to attack the United States, ignoring the warnings that war was imminent. Around 7:30 a.m., the lead Japanese pilot fires a single flare, giving the pilots the “final go” signal. “Within an hour… the US Pacific Fleet was in ruins.” The American public, writes espionage historian Ronald Drabkin in Beverly Hills Spy, quite rightly demanded: “Whose fault was it?”

Admiral Kimmel and Army General Walter Short were quickly held responsible for the disaster. Then it was “unnamed higher-ups” in Washington, and President Roosevelt himself, who were blamed. As the author notes, “there wasn’t much public evidence that would have pointed any blame at the FBI.” But Drabkin uses newly released FBI files and overlooked Japanese documents to challenge the official account.

He tells the story of a Japanese spy known as Agent Sinkawa, who was neither Japanese nor American; who was known to be a spy by the FBI but never arrested; who was a skilled naval aviator and engineer who had “personally helped redesign” the Japanese aircraft carriers used in the attack and whose spying enabled the Japanese to update the aircraft vital to its success. And he was also a British war hero, dubbed “Rutland of Jutland.”

It’s even worse for the FBI’s reputation that Frederick Rutland had lived for over half a decade in a Beverly Hills mansion paid for by Japanese Naval Intelligence. He had been under surveillance by the FBI, the US Office of Naval Intelligence (ONI) and MI5. The failure to take the threat from Japan seriously, along with their rivalry, organizational chaos, fear of national humiliation and even a murky deal with Naval Intelligence, stopped the evidence from being shared that would have led to his arrest.

Rutland’s glamorous Beverly Hills parties, with Hollywood A-listers such as Charlie Chaplin and Boris Karloff, together with his membership in Hollywood clubs like the British United Services Club, were the perfect cover for the Great War hero, who had distinguished himself in early air reconnaissance at Jutland, to chat to senior American military figures about the accuracy of their dive-bombers, the range of their fighters and Lockheed’s new top-secret fighter — and made him difficult to arrest.

But as America’s relationship with Japan deteriorated, there were FBI agents parked outside Rutland’s house, and his A-list friends were asking question about his ties to Japan. Guilt-ridden over his work, or just out of options, Rutland offered to warn the Americans and British when Japan was going to attack. But could he be trusted?

This is a “story of high ambition, daring greatness and world-changing events — but mostly, it’s a story of missed chances,” according to Drabkin, and he is right. Beverly Hills Spy is the story of the espionage war with Japan, and the damaging rivalry between intelligence services that prevented them from working together. It asks the same question asked today of researchers, business leaders and former air force pilots keen to work in China: how far can you go before you commit treason?

It was supposed to be “impossible” for the undernourished son of a Dorset day-laborer to become an officer, a gentleman and a pilot in the Royal Navy — but no one told Frederick Rutland that. He was born in extreme poverty but had “natural charisma,” along with the determination and intuitive technical skills to succeed. Even the higher-class naval officers and pilots admitted that Rutland had “undisputed guts.”

It was the afternoon of May 31, 1916, that changed Rutland’s life forever. The greatest naval battle of World War One — the Battle of Jutland —had begun in the North Sea off the Danish coast, and both sides believed the outcome would decide who won the war. It was already going badly for the British.

The Royal Navy didn’t know where the German fleet was, or how many ships it had, and the pilot chosen for what was “clearly the most important air mission in British naval history” was Frederick Rutland. In ugly weather that would have grounded most missions, Rutland managed to get his flimsy seaplane up into the stormy sky. Within ten minutes he found what he was looking for: the German fleet.

Then the German gunners located their targets, and first one and then a second huge British battle cruiser exploded below him, killing around 2,500 sailors, and soon after a third — HMS Warrior — was on fire and sinking.

Rutland’s courage stood out in an otherwise grim day for the British. He was invited to Buckingham Palace to receive the Albert Medal from King George V. It was a medal for “cases of extreme and heroic daring,” and usually awarded posthumously.

The publicity brought Rutland and his skills as a pilot and engineer “to the attention of many of the top admirals, [who] started to contact him directly for suggestions on how to operate the Royal Navy’s aircraft.” Soon, Rutland was advising them on the design of their future aircraft and aircraft carriers. But then it was all taken away from him.

He could become a pilot and an officer, but — it was made clear — not a gentleman. When in April 1918 the Royal Air Force was formed, Rutland went from being seen as a “capable and zealous officer, who with more experience could do well in higher ranks” to, Drabkin explains, “a talented officer of a lower social class, and who acted as such — unfit for higher rank.” That he kept his key role in the development of British naval aviation was no longer enough for him.

Luckily for Rutland, a new opportunity arose. Britain had at last become aware of the threat that Japan posed to its empire and in 1921 it broke off its decades-old military alliance with its former ally. “The Japanese depended on British technology, and it was no longer for sale. The only real option… was to steal it.”

Now an embittered Rutland knew what he needed to do. When he walked into the Imperial Japanese Naval Office in Westminster in late 1922, “their jaws dropped… the most accomplished British aviator in the field had simply dropped into their lap.” To confuse British intelligence, he told the RAF that he was working for Mitsubishi in Japan, lived far away from the main Japanese naval base at Yokohama — and when he was visited weekly by the Navy’s head pilot, Torao Kuwabara, and other officers, they dressed in civilian clothes.

Rutland coached Kuwabara and his staff on how to update the new Akagi and Kaga aircraft carriers — which would be used in the attack on Pearl Harbor — for the new “faster and heavier” aircraft whose all-important landing gear he was helping to design. Kuwabara wrote in his memoirs that “Rutland’s help was invaluable.”

At a private geisha party, Drabkin recounts, Captain Isoroku Yamamoto — who as admiral would lead the attack on Pearl Harbor — toasted Rutland and Kuwabara, thanking them for their help and stating that “the future of the Japanese Navy was now clear. The next war would not be fought by battleships but by aircraft flying from ships.”

Back in Britain, Rutland had a comfortable life, but he was again “deeply” missing “the public’s adulation and… the admiration of the Japanese Admiralty he once regularly impressed.” In November 1932, one year after the Japanese invasion of Manchuria, Rutland was tempted back onto the “tightrope,” this time by Japanese Naval Intelligence. This time his destination was not Japan but the United States — “somewhere like Hollywood” — because if there were a war between America and Japan, “we would need to know what is happening on the West Coast.” He was told, “You are the obvious choice. Actually, you are the only choice. Are you interested?”

It is hard to know just how significant Rutland was as a spy when there remain FBI files to be declassified, and many documents were burned by the Japanese when they surrendered in 1945. Perhaps we will never be certain. In the end, the FBI and ONI turned down Rutland’s offer to warn them because they didn’t trust him and had their own sources of intelligence. Indeed, it’s unlikely that Admiral Kimmel would have listened even so. Instead, Rutland agreed to return on a VIP flight to London to discuss his offer further. He thought it was a trap, and it was. He was questioned by intelligence officer Ian Fleming, creator of James Bond. He never saw Beverly Hills again — but he never confessed.

The outbreak of war with Japan meant that on December 8, 1941, Rutland was interned without trial under wartime powers as he rep- resented “an imminent danger to the realm.” Winston Churchill refused to intervene on behalf of Rutland’s “powerful friends,” who believed the war hero was innocent, as some people still do today. He was released two years later, angry and determined to cause trouble for MI5 and likely still under MI5 surveillance. Rutland was found dead in January 1949. The official report called it suicide, but some think he could have been murdered. The mystery of his end is a fitting conclusion to this gripping, perplexing book.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply