On September 23, 1951, King George VI was operated on for cancer. It was a grueling, dangerous procedure, conducted at Buckingham Palace by Clement Price Thomas, a leading chest surgeon. The king, unsurprisingly, was miserable at the idea, saying, “if it’s going to help me get well again, I don’t mind, but the very idea of the surgeon’s knife again is hell.” Yet he was kept unaware of the seriousness of his illness, instead being informed that the cause of his health problem was nothing more urgent than obstruction in one of his bronchial tubes, which would require a “resection” of the lung, and that it would cure the “pneumonitis” that he believed he was suffering from.

It was given out that the operation was a success, and a day of national thanksgiving was declared on December 2. Unfortunately, this was dangerously premature, as the truth was known to those around the king. The politician Harold Nicolson wrote in his diary on September 24, “the King pretty bad. Nobody can talk about anything else — and the election is forgotten.” He saw Churchill’s personal physician Lord Moran at a social event the day after the operation. In response to his unspoken question about the chances of recovery, the doctor gravely shook his head. By October 10, a formal meeting was held, with the king’s private secretary Alan Lascelles and others present, to discuss the arrangements for what would happen in the event of the “demise of the crown.”

This duly came to pass on February 6, 1952, when the king died in his sleep of a coronary thrombosis, at the age of fifty-six, resulting in the immediate succession of his daughter Princess Elizabeth, who was only twenty-five. She was informed of her new responsibilities while in Kenya; Nicolson said, “She became Queen while perched in a tree in Africa watching the rhinoceros come down to the pool to drink.” It was a moment of seismic change for Britain — and the world. The young, untested Elizabeth II took on unimaginable responsibilities at a time when questions were being asked about the point of the monarchy and whether, in the postwar era, there was any need for it or if it was simply a backwards-looking anachronism. As some pointed out, the United States had not had a monarch since George III and seemed to be managing perfectly well.

The reign of Elizabeth was, of course, a great success, both in longevity and in terms of reputation. When she died on September 8, 2022, at the age of ninety-six, she was widely hailed as the most consequential monarch since Queen Victoria. In many regards she was a more impressive figure, who not only revived the reputation of the British royal family from the doldrums it had declined into but refreshed it and put any suggestions of republican sympathy in the shade. Even at the low points of her reign — the “annus horribilis” of 1992; the anger at her slow public response to the death of Diana in August 1997 — there was never any serious suggestion that the institution was not fit for purpose.

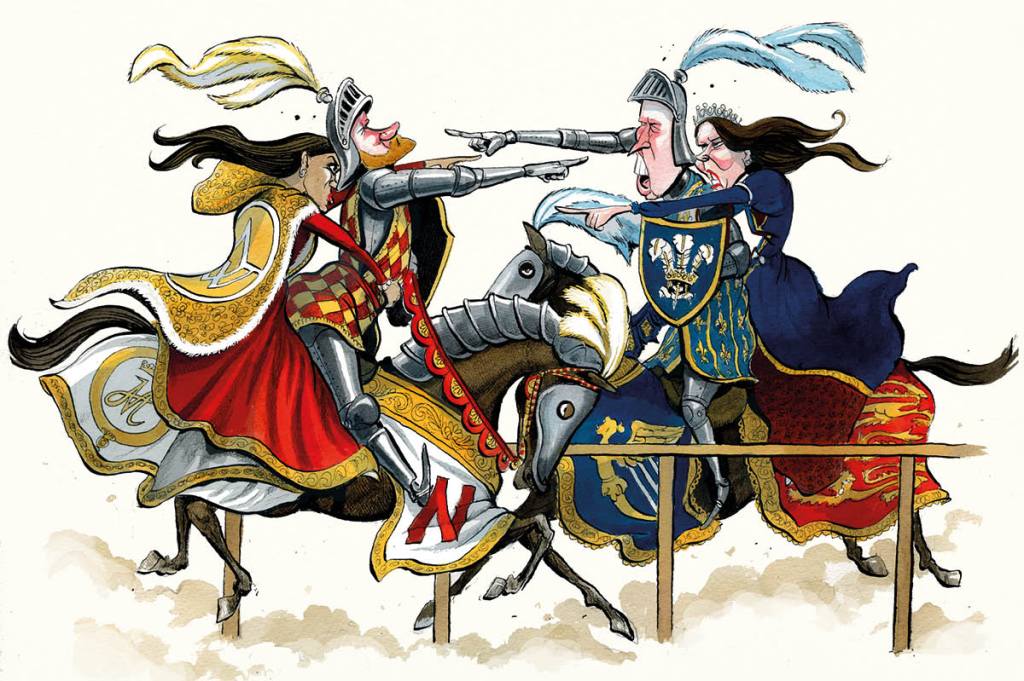

Eighteen months after her death, however, matters have changed dramatically. The soap opera of the fraternal battles between Prince William and Prince Harry has been lavishly documented all over the world and shows few signs of coming to an end. Harry’s decision to write his self-aggrandizing, at times utterly bizarre memoir Spare only further damaged relations between him and the rest of his family. The media have feasted on the apparently endless stories of his estrangement from them, exacerbated, naturally, by the influence of his wife, who remains almost comically unpopular in Britain and who shows few if any signs of attempting to improve her standing in a country that she seems to regard as backward and racist.

Yet all this has paled into insignificance since the recent revelations that King Charles is suffering from cancer: the first time a monarch has been seriously ill since his grandfather George VI seventy years ago. There has been a steady drip-feed of information into the public domain from palace sources, which has struck an uneasy balance between candor and obfuscation. While previously details of the royal family’s health issues have been shrouded in mystery — the Queen Mother had cancer twice, once in her sixties and once in her eighties, but this was not reported until years after her death, despite widespread public rumors — Charles has now decided that openness is the best policy. On January 17, it was announced that he was to enter the London Clinic, an exclusive private hospital, for a prostate operation, and then, on February 5, the news was broadcast on live television that the king had cancer. The type was not revealed, save to clarify that it was not prostate cancer, and that treatment had begun immediately.

It has not helped that the Princess of Wales also had to enter the London Clinic in January for an operation and a prolonged recovery. The nature of her illness has not been disclosed publicly save to clarify that it was not cancer. Stories have circulated, some more likely than others, but the dual indisposition of two of the main “working royals” has left “the Firm,” as the institution is familiarly known, with a dilemma. Should the likes of Prince William and the Queen take on ever-greater responsibilities, or should other currently minor figures like Princess Beatrice and Princess Eugenie be pressed into public service, taken away from their demanding jobs in art and software companies? Or should the royal family simply do less and gradually withdraw from public life?

Nobody has seriously advocated the latter course of action, as it is known that it would be increasingly difficult to find widespread support for an institution that takes public money and does little to repay it. (The age-old argument that the monarchy is “good for tourism” has taken an increasing battering in the post-Covid era, but nobody, save a few disgruntled republicans, has made any serious public attempt to disprove it.) Yet if Charles’s illness proves to be more serious than is hoped, and he must either scale back his responsibilities or follow the example of his great-uncle Edward VIII and abdicate in favor of his son the Prince of Wales, there will be increasing questions asked about whether the monarchy can sustain a second period of change.

As a royal historian and present-day chronicler of the institution, I do not pretend to be Cassandra, able to predict the future. If anything, I have erred on the side of pessimism in the past. I suggested that Elizabeth II’s death was likely to be the spur that led to a rise in republican sentiment in Britain, but in fact, any fillip that the late Queen’s demise produced instead firmed up public support for the monarchy, perhaps in the spirit of “better the devil you know.” Nobody seems to want a presidential system in the United Kingdom — “President Boris Johnson” would be a step too far for anyone — and so, buoyed up by a mixture of patriotism, inertia and carefully measured propaganda, the royal family seems unlikely to be challenged by external forces any time soon.

Instead, the greatest threat to its survival will come from within. King Charles is a known quantity on the world stage, liked or disliked. Whether or not his reputation suffered an insuperable blow from his ill-fated marriage to Princess Diana — something that, for most people under forty, is rapidly turning into ancient history anyway — he is still king for as long as he can be, or wishes to be. His elder son is another matter. The disclosures about William in Spare were somewhere between tawdry and embarrassing — and combined with various internet rumors about his private life, there is a general sense that the Prince of Wales’s PR machine is not functioning as smoothly as it should. Which is fine, if your father has a decade or two left to rule, but rather more difficult if there’s any chance that you might have to accede to the throne in the next couple of years.

What will the reign of William V be like? It is presently easier to define the next monarch by what he doesn’t believe in rather than what he does. He is no great adherent of the Commonwealth; has only a passing interest, at best, in the Church of England, of which one day he will be head; and he lacks his father’s philosophical and intellectual leanings. King Charles had the writer Laurens van der Post as his mentor, while his son associates with high-end property developers and nightclub impresarios. His reign will probably be a stylistic throwback to those of Edward VIII and George IV, even if William himself is far more dutiful and less glamorous than either of those controversial figures. It will be his wife who is expected to bring compassion and sensitivity to the monarchy, and William will grimace a lot, openly bored by the responsibilities that any king has to put up with.

It is impossible to know when his turn to take over the reins will be. His grandmother had barely any time to acclimatize to the idea, while his father had decades to prepare for it. In all likelihood, William will have something in between. He will then be faced with a largely thankless and demanding task, which he may well cavil at, but he will also have known, since birth, that this will be his destiny, as it has been for all his family. The question remains whether Prince George — whenever this poisoned chalice is passed onto him — will inherit a monarchy that is in any way recognizable from his great-grandmother’s reign. After centuries of conservatism and continuity, all expressed through the adage “never complain, never explain,” chances are that the excess of complaining and explaining that has been epitomized by Prince Harry will be what we all expect from the royal family in the future.

Everyone will wish King Charles the best for his recovery, and hope that the remainder of his reign is less eventful than the past couple of years have been. But given how tumultuous the royal institution has become, you would not bet against matters becoming even more dramatic. Fasten your seatbelts, ladies and gentlemen: we are in for a bumpy ride.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s April 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply