The corruption of its democracy is one of America’s oldest yet most surprising habits. Edgar Allan Poe, it is believed, died after the ordeal of ‘cooping’: an informal exercise in getting out the vote, in which an often forcibly inebriated man was marched from booth to booth and made to vote for the same candidate each time.

The voters of Massachusetts’s 4th District, compelled by a party machine to endorse Joseph P. Kennedy III, will know the feeling. Indeed, John F. Kennedy’s victory in the 1960 elections is said to have depended on the stuffing of ballots in the Chicago of Mayor Richard J. Daley — and possibly on the intervention in Cook County by the crime boss Sam Giancana. Kennedy went on to win Illinois by 8,000 votes and to take the White House.

However endemic electoral corruption was in the past, nothing quite matches the scale of today’s disillusionment with democracy. Americans are raging against the electoral machine in a way they have never done before. Whoever wins the White House in November is going to have an uphill struggle convincing a skeptical public that he or she is the genuine choice of the American people and has got there by fair means.

Come what may, many will suspect dark forces at work. The taint of meddling still hangs over the 2016 results. Robert Mueller may not have proven collusion between Trump and Vladimir Putin, but he did turn up such paradigms of the lobbyist’s art as Paul Manafort and George Nader. Manafort, Trump’s former campaign manager, was alleged to have been an intermediary between the Trump campaign and Russian interests. He is now in prison after being convicted of conspiracy to defraud the United States and failure to register as a foreign agent, among other things. Nader was questioned by Mueller’s agents about claims that the United Arab Emirates had assisted the Trump campaign. He is now indicted for, investigators believe, funneling millions of dollars in foreign donations through a straw-man to Hillary Clinton’s 2016 campaign. He has already pleaded guilty to charges of child pornography and transportation of a minor for sex — crimes which were uncovered as a result of the Mueller inquiry.

Perhaps most disturbing is how quickly the Democrats, who still claim the moral high ground, lost interest in Mueller’s more important findings the moment they realized he had not ‘gotten Trump’. In doing so, they succeeded in proving what many suspected: that they are not motivated by a desire to clean up American politics, only by narrow partisan objectives. Many feel the same about their failed impeachment of Trump.

Never attribute to malice that which can be attributed to incompetence, they say. Sure enough, there is plenty of the latter at work in national politics. The Democratic side of the presidential race has become a muddle, with too many candidates and no clear message. Of all democratic processes in America, the Iowa caucuses ought to stand out for the direct way in which they harness the will of the people. Where else do voters, many gathering in front rooms or high-school gymnasiums to cast their choice, get so close to the levers of power? Yet the Iowa Democrats contrived an innovative, high-tech way to mess the whole thing up. This year’s caucuses will be remembered, not for the vision of any candidate, but for the endless wait for the results and how in the meantime, as in Alice in Wonderland’s own caucus race, everyone was improbably said to have won.

What happened in Iowa was almost a digital form of ‘cooping’. As Andrew Cockburn explains, the Democratic national leadership is at odds with the membership. This edition of the magazine focuses on the Democrats’ deep problems, but their party is not alone in having a disconnect between its leaders and its ordinary members: the Republicans went through similar agonies over Donald Trump.

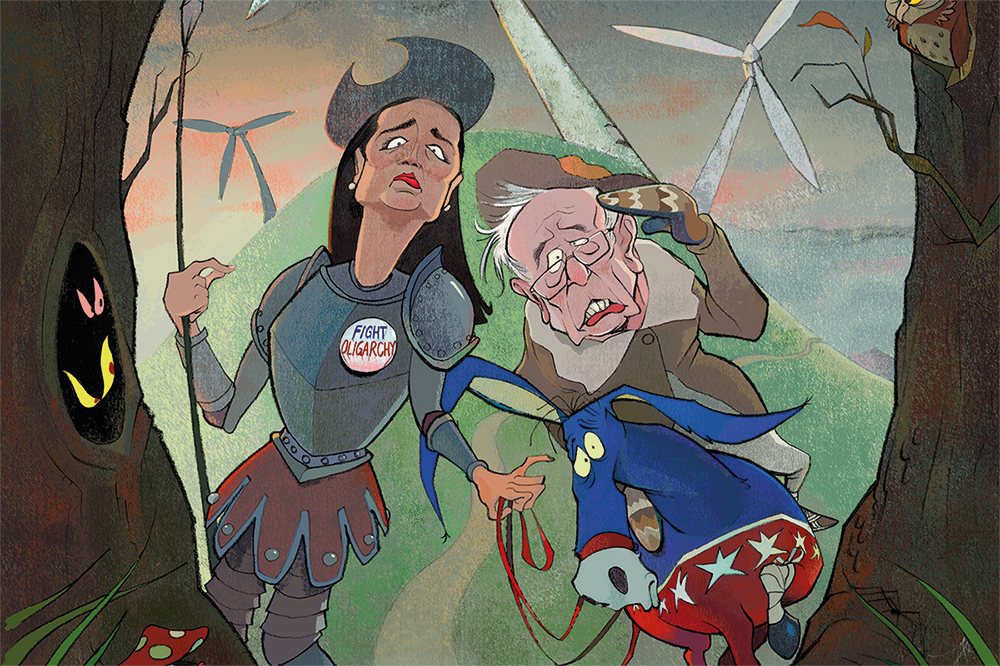

At the heart of the Democrats’ problems is a growing spirit of insurgency against political elites. We see this across the developed world: in Britain with Brexit or, as Dominic Green points out, with Jeremy Corbyn; in France with Emmanuel Macron; in Italy with Lega; in Spain with Podemos; the list goes on. Old established parties have grown deaf to their electorates and duly suffer at the ballot. They then blame sinister and somewhat unreal forces — populism, racism, Russian puppeteers.

In 2016, the Democratic establishment dodged the insurgency bullet: the Democratic National Committee (DNC) managed to overrule the Democratic primary voters’ enthusiasm for Bernie Sanders and inserted the establishment choice, Hillary Clinton. The reverse happened to the Republicans. Their rank and file overthrew the party’s preferred candidates and selected a presidential nominee who, like Bernie Sanders with the Democrats, had only recently discovered he was a Republican.

We all know how that ended: the insurgent went on to win, in spite of his many character faults. The lesson was that in the present atmosphere you want your candidate to be, or to appear to be, on the side of the people against the political establishment. A more responsive Democratic leadership would have accepted Sanders’s nomination in 2016. Had they done so, they would have neutralized Trump’s pitch as the anti-establishment choice.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s March 2020 US edition. Subscribe here.