The greatest rivalry in soccer for the past decade is coming to an end. Managers Jürgen Klopp and Pep Guardiola clashed in thirty games across Germany and England, but neither came out decisively on top (their final meeting was a 1-1 draw earlier this month). In May, Klopp will leave Liverpool for good. It’s a shame that two of the best managers of all time may never face each other again, because their rivalry has raised the caliber of the sport so spectacularly.

Klopp and Guardiola tinkered relentlessly with their squads, tweaking formations, positions and playing styles in order to best one another. In doing so, they redefined the cutting edge of soccer season after season, and their dominance in all tournaments forced other managers to adapt their own styles so as not to fall behind. There will be much talk about their tactical brilliance in the coming months, but the man who really deserves the praise is the one who inspired them both, the godfather of modern soccer: Johan Cruyff.

‘Playing football is simple, but playing simple football is the hardest thing there is,’ Cruyff liked to say

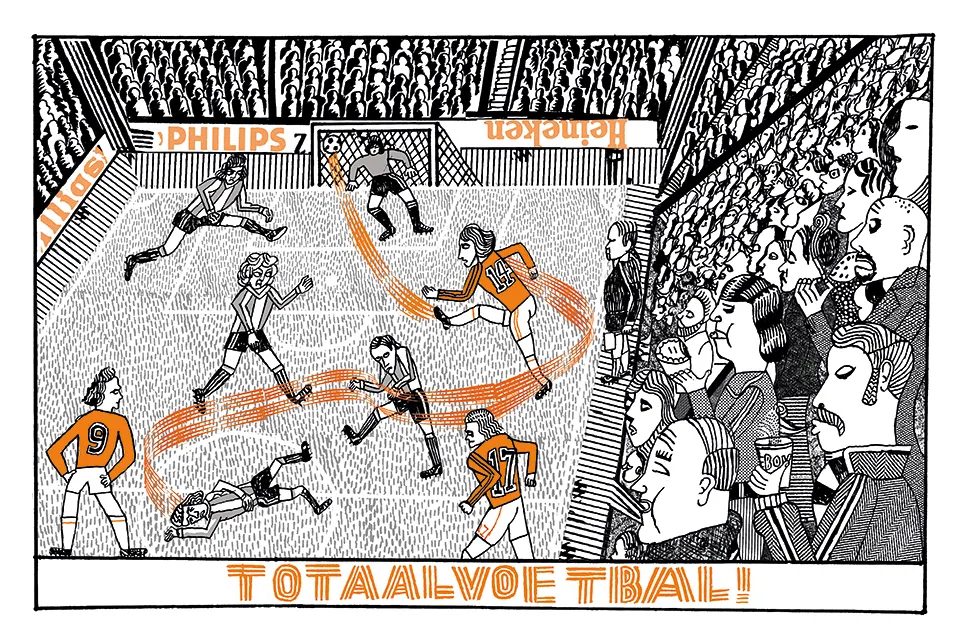

When Cruyff was a seventeen-year-old novice at Ajax in Amsterdam in 1965, Rinus Michels had just become the club’s manager. Michels had himself developed a revolutionary attacking approach to the sport which relied on two tenets: players interchanging positions on the attack to confound the opposition’s defense, and making runs into space between opposition players in lieu of playing man-for-man. He called this approach “total football.” Cruyff was the perfect disciple for Michels. He was never the most athletic player — he smoked twenty a day — but he, like Michels, understood that soccer is a cerebral exercise as much as a physical one. “Playing football is simple, but playing simple football is the hardest thing there is,” he liked to say. His sayings were mocked by some, but young students repeated them like mantras, and later they were distilled into his “fourteen rules” of soccer. The fourteenth was to “bring beauty to the sport,” which he did, and still does today.

This isn’t to say total football didn’t have teething problems. An overwhelming emphasis on attacking made it exciting, but also meant teams could be very vulnerable to counterattacks. The first major obstacle was in the 1969 European Cup final where Ajax played AC Milan. The match was a clash of two rival footballing schools: Dutch total football and its antithesis, the Italian catenaccio, or “door-bolt.” Mastered by Milan coach Nereo Rocco, catenaccio was centered on a rigid system of defense that would lock out the opposing team as players then battled man-for-man across the pitch. The mood in the stadium was feverish ahead of the match and kick-off was delayed by fifteen minutes because there were so many members of the press still on the pitch. In the Milan dressing room, Rocco barked orders at his players, instructing his defenders to “kick everything that moves, if it’s the ball, even better” and telling his main defender to man-mark the slippery Cruyff “from the dressing room to the toilet.” His team’s doggedness paid off. Milan beat Ajax 4-1.

But within two years, after a few minor changes to the formation, total football was back. Michels and Cruyff dropped a winger into a freer midfield position, now recognized as a 4-3-3 — and signed a new German defender, Horst Blankenburg. Blankenburg immediately fitted into Ajax’s set-up where directness on and off the pitch was a prerequisite. “I’m Horst, I’m a Kraut and I’ve come to play football with you,” he announced on his arrival. Ajax won three consecutive European Cups — the first team to do so since Real Madrid in the 1950s.

Even as a player, Cruyff experimented with the total football formula. At the 1974 World Cup he persuaded Michels, now the Dutch national team manager, to select a different goalkeeper who was better with the ball at his feet despite being a worse shot-stopper. Cruyff’s reasoning was that he could also be called upon to defend in dangerous moments. The role of the sweeper-keeper was born, one that is still seen in the best teams fifty years on.

Like all great innovations, this one forced change in the competition too. Michels and Cruyff’s success meant other teams had to respond in kind. As the Times of London reported after one of the club’s European triumphs: “Ajax proved that creative attack is the real lifeblood of the game… that blanket defense can be outwitted and outmaneuvered.”

Cruyff became manager at Ajax, then at Barcelona between 1988 and 1996, and in his first tactics session he marked the positions on the board in the classic 4-3-3 he had played in some fifteen years before. “What the hell is this?” Eusebio Sacristán, a starting midfielder, later recounted. “We couldn’t believe how many attackers were in the team, and how few defenders.” Younger players felt that total football had had its day, but Cruyff started developing Barcelona’s “Dream Team,” which would go on to win four consecutive league titles and the club’s first European Cup.

‘Before Cruyff came we didn’t have a cathedral of football,’ Guardiola said. ‘It was built by him, stone by stone’

It was during the European Cup winning season that Guardiola emerged as one of soccer’s most promising midfielders and one of Cruyff’s most loyal disciples. Cruyff had plucked Guardiola from relative obscurity at Barcelona’s youth academy, La Masia, and promoted him to the starting eleven, just as Michels had done to him some two decades before. After retiring as a player, Guardiola also managed Barcelona, where he bested Cruyff in holding the record for trophies won. “Before Cruyff came we didn’t have a cathedral of football,” Guardiola said a few years ago. “It was built by Johan Cruyff, stone by stone.” Guardiola’s own tactics are very different from Cruyff’s, prioritizing possession and strict positional play as opposed to free-flowing attacks, but he acknowledges the total-football philosophy which he inherited: “The basis comes from before, from my mentor, from Cruyff.”

Although Barcelona was Cruyff’s last job — he suffered a heart attack in 1991 and later quit coaching — he spent the rest of his life helping other coaches and took up advising roles at his two main clubs, Ajax and Barcelona. Just weeks before his death in 2016 he spent some time in Haifa, Israel, with the coach Peter Bosz, then a relatively obscure manager who had had limited success with some middling Dutch clubs. “In one week I learned enough for ten years,” Bosz remembered fondly.

Bosz has been a Cruyff acolyte since he was a child and obsessed with total football’s prowess as a free-flowing, attacking game. As a teenager he collected Cruyff’s sayings in a scrapbook. As a player for Ajax’s rivals Feyenoord, he would try to spy on their training sessions to see how Cruyff’s former team played — “How is it at Ajax?” he often dreamed. Sadly, he never got to play under Cruyff. Bosz was a strong defensive midfielder, a destroyer, which ironically was the opposite of the soccer he aspired to play. Such was Bosz’s affinity with total football that when he was on the bench, he admitted he could give himself “a happy afternoon” and “give one to the fans.”

After his week with Cruyff, Bosz was offered the Ajax job for the next season. A supposed fairytale takeover of the side started promisingly. “I never thought I’d see an Ajax team playing this way again,” says Cruyff’s biographer Auke Kok. But Bosz left for Dortmund that summer, where he lasted less than a year, later followed by stints at Leverkusen and Lyon. Now back in the Netherlands, at PSV in Eindhoven, Bosz is still unrelenting in his faith in total football. So far it’s paying off. PSV currently have the best domestic record on the continent, twenty-three wins and three draws, and are likely to remain undefeated — it’s been twenty years since a top-flight English team managed to do the same.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply