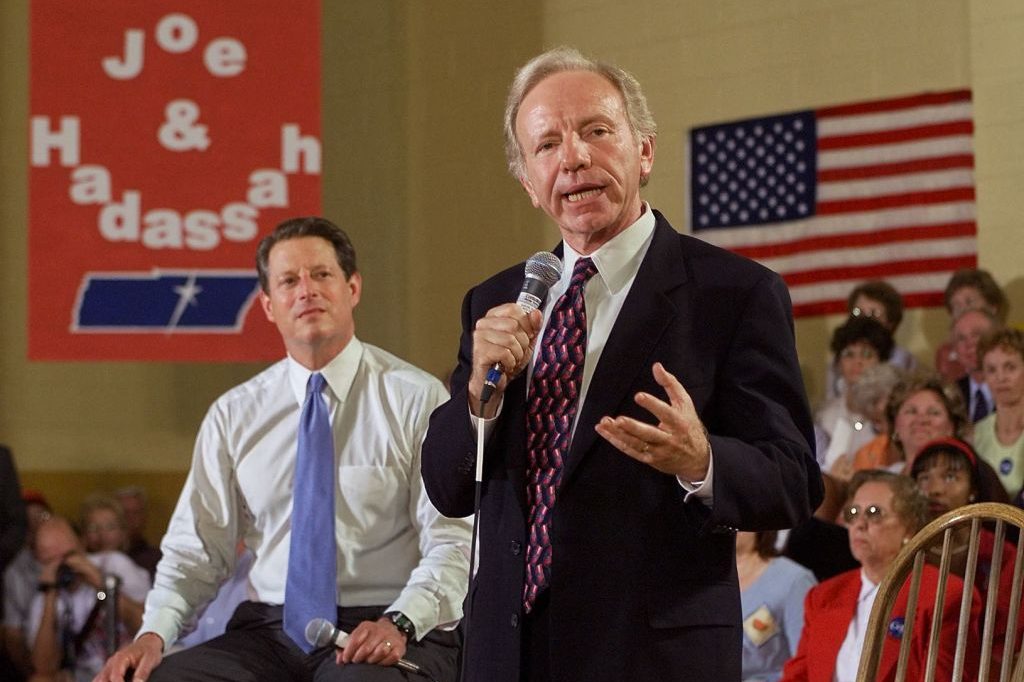

It is impossible for me to think of an American in politics who lived a life as full of hope as Joe Lieberman. Long past the point where all others would have given up and thrown their hands in the air in frustration, Lieberman was making the case even to the end for an end to partisan warfare, and a willingness to work across party lines to make a difference for the American people. Just last week he was out in public pushing for the No Labels ticket — a thorn in the side of both major parties — while criticizing Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer over his speech on Israel. Joe was always evenhanded in his critiques — he didn’t know how to do it any other way.

His time in the Senate often saw him navigating through whirlwinds on either side, as partisans became increasingly frustrated with his resolve that tested members in both parties and ensured no one would get everything they wanted. One week the left side of the editorial pages would love him. The next, he was a menace to progress who should be tossed from the Democratic caucus. He paid it no mind.

The point was what he believed in his conscience was right — not who he worked with to get there. And he was willing to work with anyone toward that end. People thought of him as a centrist. But the truth was he would take positions on the left and on the right — he wasn’t just a weathervane, muddling along like a politician who lacks a spine. He just believed the right thing was the right thing, and believed pursuing that for the country was the highest aim.

In Lieberman’s book, In Praise of Public Life, in which he argues that the solution to lack of trust in government is for more everyday people to get involved in our politics, his prologue opens:

There are times, now and then, when my mother will read something critical about me in the newspapers, or she’ll hear the fatigue in my voice during an evening phone conversation from my home in Washington to hers in Connecticut.

“Sweetheart,” she’ll say, in that voice I’ve heard all my life, “do you really need this?”

I laugh and answer, “Yes, Mom, I really do need this. I love it.”

He really did love it. I know this because I got to know Joe Lieberman as a politician before I was fortunate enough to know him as a friend. Some of my fondest memories of him are sitting outside at dusk in Arizona, at the end of the dinner table with John McCain, debating a point of foreign or domestic policy for hours as others drifted away in discussions that were marked by disagreement, not disrespect, but with a fair bit of ball-busting and laughter along the way.

When John died, Joe and his wife Hadassah were there for us and our family at every turn. They supported us in every small thing that matters through the death of a towering figure who also happens to be a beloved father, mentor and a symbol for so many. And whenever the opportunity arose to get together in New York, it would be a chance to reminisce, but also to think about the future of the country — a future about which Joe was always hopeful.

It’s a strange thing what happened after the fractious controversy of the 2000 election. For Al Gore, it seemed to break him. For Joe, it was as if he had an irrepressible quality to move forward without regret. He never let politics poison him. He always thought it was worth doing. Again, from In Praise of Public Life:

The summary of our aspirations was in the Hebrew phrase tikkun olam, which is translated “to improve the world,” or “to repair the world,” or more boldly “to complete the creation which God began.” In any translation, this concept of tikkun olam presumes the inherent but unfulfilled goodness of people and requires action for the benefit of the community. It accepts our imperfections and concludes that we, as individuals and as a society, are constantly in the process of improving and becoming complete. Each of us has the opportunity and responsibility to advance that process both within ourselves and within the wider world around us. As Rabbi Tarfon says in the Talmud, “The day is short and there is much work to be done. You are not required to complete the work yourself, but you cannot withdraw from it either.”

We will miss Joe Lieberman’s voice of reason in a fractious age. But if we are about coming together, about becoming complete, we will need more people who heed what he had to say. RIP.

Leave a Reply