The drive from Islamabad to Multan takes about eight hours. We passed through fields of citrus fruit and farmers tending weed-burning fires. Boys carried giant bunches of twigs over their heads or zipped by on old Honda 70s, balancing water tubs. All had early-Beatles haircuts and wore the shalwar kameez, the Punjabi suit of lightweight trousers and a tunic.

Multanis, distinguished by their good looks and their own musical dialect, are called meethi churiyans by other Punjabis, meaning “sweet knives.” They are charming and generous, serving up piles of warm chapati and mutton chops, before stinging you with a hefty bill. Cars and rickshaws tussle for space on the road, no one gives way without excessive honking, and the motorbikes, sometimes carrying whole families, jauntily weave in and out, their protruding mirrors deliberately removed.

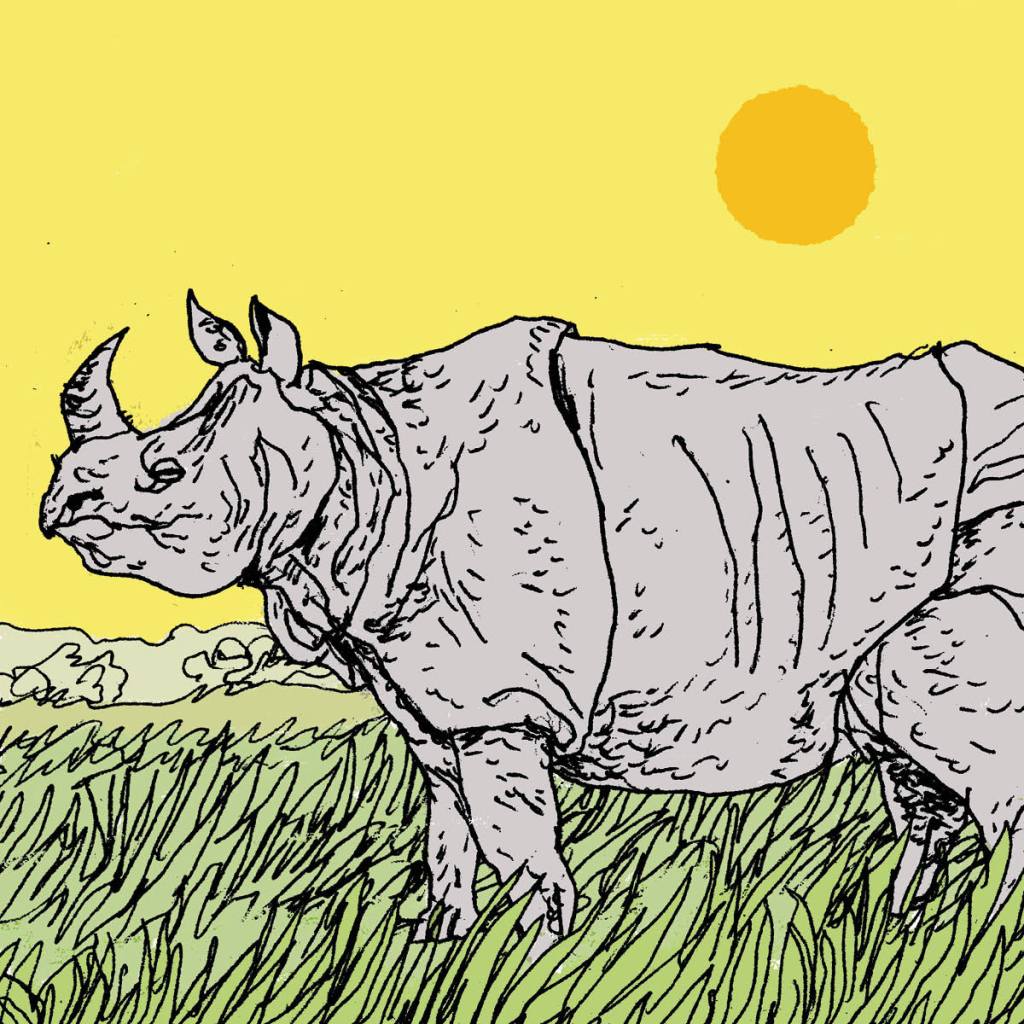

I’m here as part of an expedition sponsored by the Aspinall Foundation (set up by my grandfather John Aspinall in 1976) to find new territory for the greater one-horned or Indian, rhino. Leading the field in successful animal reintroductions, the foundation has returned lowland gorillas to West Africa, Javan gibbons and langurs to Indonesia, European bison to Romania and Przewalski’s horses to Mongolia. With Ben Goldsmith’s Pakistani Environmental Trust (PET), it now hopes to reintroduce the greater one-horned rhinoceros to its ancient heartland.

You don’t tend to think of rhinos when you think of Pakistan but these mega-herbivores once roamed freely over the fertile plains of the Indus Valley. In the sixteenth century, the Mughal emperor Babur wrote about hunting them in what is today called the Peshawar Basin, about ninety miles northwest of Islamabad. Eventually, the Indian rhinoceros met the same fate as the Indian elephant, the Asiatic lion and the Asiatic cheetah, hunted to the brink. By 1900, there were fewer than 200 in the wild. But in one of Asia’s greatest conservation success stories, they now number about 4,000, mostly residing in northeastern India and the Terai grasslands of Nepal.

Since I am writing a book about my grandfather, I’ve decided to tag along with the reintroduction team, which consists of Amos Courage, the foundation’s director of overseas projects, Tony King, conservation and reintroduction coordinator (and keen birdwatcher) and our two partners from the PET.

A successful reintroduction project first needs to establish a breeding sanctuary; a manageable, enclosed area of several hundred acres, with shade, a water source and suitable vegetation. Once the rhino crash (herd) grows, they’ll need a much larger release site, ideally contiguous, which they can be moved to. This of course needs to be protected from poachers.

Asian conservation is a funny affair. At one of the proposed sites, an estate two hours’ drive from the capital, we met our local host. He greeted us in perfect English and cashmere Louis Vuitton, saying he had returned from Dubai specially to show us around.

With him was a young Englishman. Wearing a brown suede bomber and aviator shades, Bertie asked about our project and then told us about his own. He was trying to reintroduce foxhunting to Pakistan: “They are very kindly building me some kennels here. We’re trying to re-establish the Peshawar Vale Hunt, first formed in 1863.”

Swept up in dreams of horsemanship, I asked if we could ride out to see the land. Saddles were promptly fetched and I found myself atop a large brown stallion. We began a three-mile ride through fields of wheat and sugarcane and the seventy or so villages which made up the estate.

With chafed thighs and a splitting pain in my backside, I watched a display known as “tent-pegging.” This sport involves galloping, lance held high, toward a little block of wood pegged into the ground and trying to spear it up as you pass. The Household Cavalry still practice it today (it has its own World Cup), having picked up the technique during the Raj from Indian cavalry who attacked their unsuspecting enemies by collapsing their tents before mercilessly skewering the trapped wretches.

On the ride back, my horse panicked, reared and, unbeknown to me, hit the hood of the support vehicle. I was not made aware of this until afterward, when I was back at the compound, sipping mango juice and feeling happy to be alive. “Your horse put a dent in my car,” said our host. My efforts to compensate him fell on deaf, rather furious ears. To add insult to injury, Bertie then whispered I’d developed a gaping hole in my trousers, through which my testicles were beginning to elope — the sort of thing that can get one beheaded in Pakistan.

Luckily our host’s brother, “the Prince,” seemed a kindly man, giving us a full tour of the estate. Behind the mansion stretched a great brick courtyard where two young boys played cricket, using a stone block for stumps. At the old barracks, now cattle sheds, a rare single-humped Brahman bull was dragged from his slumber. We were shown around the stables, shepherded by an elderly clan of turbaned men wearing kurtas and blankets. The eldest, swaddled in white, an assault rifle dangling at his side, had a perfectly curled silver mustache. One by one, the Friesians were led out of the dairy barn and paraded before us in the fading light.

Our Prince was a true romantic, clinging passionately to the old ways. He is a Brexiteer and expressed peculiarly grave doubts about Romania joining the European Union (the country joined in 2007).

The estate has its own parliament, prison and mosque. The family is responsible not only for appointing all the local administrators but also for settling villagers’ personal grievances. It is a sort of feudal system, built on patronage and maintained through inter- marriage within the wider kinship group. This ancient form of society holds the country back, but it’s also what holds it together.

As we left for another rhino site, we learned that we would be not sleeping at our guesthouse because it had been given over to an Emirati sheikh who had flown in to hunt houbara bustards. Tony’s ears pricked up at the mention of this endangered bird. International and local wildlife protection laws have banned the hunting of houbaras but occasionally a “special license” is granted by the Pakistani government. Every winter, the birds migrate from Central Asia to Pakistan. Unfortunately for them, the sheikhs migrate too.

Pretty soon some Indian rhinos could also be making the trip, returning to ancestral lands after centuries of an eked-out existence. Rhinos are a keystone species, meaning their presence helps shape and regenerate entire ecosystems. They have been called “nature’s landscape engineers” for how their grazing maintains grasslands, which today act as vital carbon sinks. They won’t be easy neighbors in a densely populated country like Pakistan, but they have every right to be here. The foxhounds are, well… another story.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s May 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply