Who would have thought that the battle between champions of old-school socialism and contemporary identity politics for the post of general secretary of Unify, a fictitious British trade union, would make for such riveting reading?

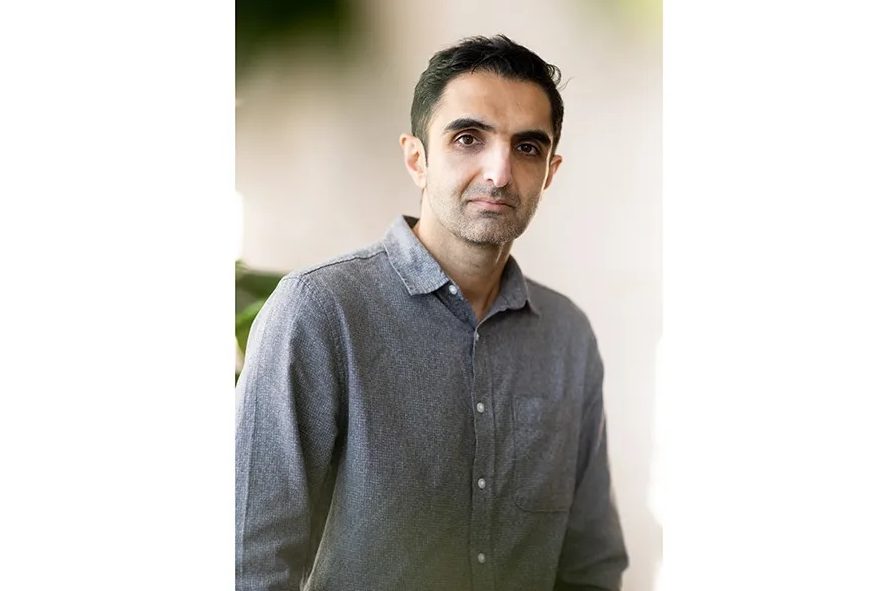

Nayan Olak and Megha Sharma have little in common save their skin color. He is the son of corner shopkeepers, who started work on the factory floor at sixteen and is now the union’s head of workplace disciplinary actions. She is the daughter of a non-dom property magnate and recently appointed head of diversity, equity and inclusion. Their political priorities are neatly encapsulated in their job titles.

While never explicitly favoring either candidate, Sunjeev Sahota makes his own sympathies clear by showing how Megha wilfully misrepresents both Nayan’s actions and arguments (not the only occasion in the novel when a man is brought down by what Nayan describes as “typical private-school, entitled shit”) and by Nayan’s heartfelt pleas for working people to stand together against those “who would create splits, based on our background, our gender, even our race.”

Nayan is deeply conflicted in his private as well as his professional life. The deaths of his mother and four-year-old son in an arson attack two decades earlier have left him emotionally scarred. Now divorced and caring for his demented father, he feels an intense attraction to Helen, a near-contemporary of his sister’s, who has recently returned to their home town of Chesterfield with her teenage son. Helen’s involvement in the arson attack on his family is evident from the start, although Sahota skillfully withholds its true nature until the final pages of the book.

The prose is spare, characterization rich and nuanced, and the portrayal of the psychological effects of urban desolation approaches that of Dickens in Our Mutual Friend. The sole miscalculation made by Sahota lies in the narrative voice. His narrator, Sajjan Dhanoa, is a local boy turned metropolitan novelist, who is drawn back to Chesterfield, a town he hates, for reasons he fails to understand. Sajjan pieces the story together from the accounts of Nayan, Megha and their associates. He is at once a bystander, whose own family connections to Nayan turn out to be significant, and the omniscient chronicler of his characters’ thoughts. In one uneasy Pirandellian passage, Helen looks to him to discover her motivation. Such metafictional flourishes aside, The Spoiled Heart is a highly accomplished and timely political morality tale.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply