Poetry is politics in the Yemen. When the last imam of Yemen, who was also the hereditary ruler, was deposed in a coup in 1962, it was a local poet who announced the change of regime on the radio, in verse of course. And the current al-Houthi regime in the north of the country, like all its predecessors, asserts its legitimacy, confounds its enemies and rallies its supporters through poetry.

As an aspect of their cause, they have consciously avoided high-Arabic poetry — a literate, urban cultural form — and have made use of the zamil tradition, which immediately speaks not of the palaces of emirs and princes, but takes the listener to sit beside the farmers and Bedouin shepherds in the villages and hills.

Zamil poetry shapes the great events of life — from weddings to war

Zamil oral poetry is, under a variety of names, an Arabia-wide practice. Banish any memories you might have of poetry recitals here — the small gathering of shy writers reading myopically from their slim volumes. Instead imagine a vast tent in which a cocksure young warrior, one hand on his sword, the other puncturing the air, is chanting his verses to a striking rhythm set up by a drum and supported by the melancholic melody of a flute, the entire audience excitedly singing along to the refrain-like couplets.

This is zamil (plural zawamil) which, unlike the literate traditions of Arabic poetry, is not governed by precise rules of meter and internal rhyme, but is ready to be shaped for any of the great events of life. It might be used to celebrate a wedding — and to generously introduce the two families to each other; there might be duels between rival poets brandishing rival politics with humor or deadly zeal (zajal); there can be eulogies for the dead (madih), praise of the tribe (qitah), denigration of the enemy (hija’) and hamasah, calls to war.

Marvelously it may be used by a revered old sheikh in an arbitration, not so much when making a judgment over a dispute, but in the lead up to the settlement of an argument to summarize and praise both sides.

Winds — either gentle lovable breezes or violent tornadoes turning the dry wadi floor into a devastating flood — are ever popular analogies. The much-burdened camel is an irresistible image for the experience of the common man.

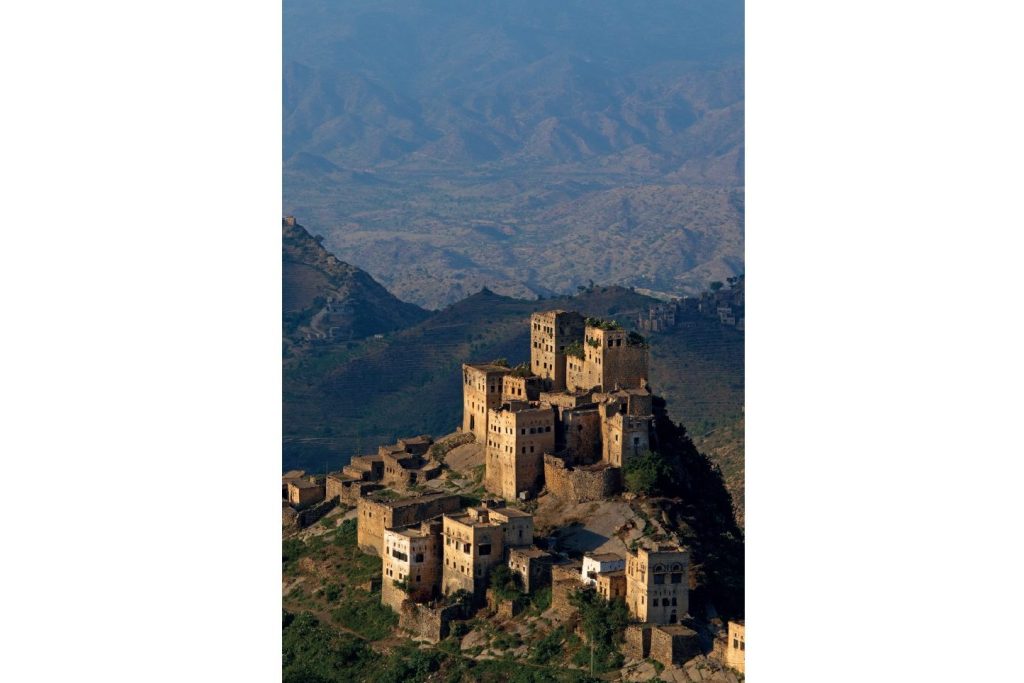

At its best this oral poetry becomes the articulate, free-talking spirit of the community, relishing intimate details of the local landscape, the local dialect, mythology and slang which may be incomprehensible to the next-door valley, let alone the rest of the Arab world. Yemen is thick with local identities, complete with recognizably different accents and old memories of self-governing sheikhdoms and rival dynasties. Yet the most-loved verses escape their locality and can have a vast reach, originally through cassette recordings, but now to an ever-wider audience through the medium of the mobile phone and the internet. Today’s viral offerings combine solo voices of passionate integrity with gritty chorus refrains sung by male warriors.

One of the most popular young male singers championing the al-Houthi cause is Issa al-Laith. His poems “Prophet Muhammad Unites Us” and “Force of Great Might” could make a useful introduction. This zamil tradition in the Yemen is exactly mirrored by nabati, created by the rural, semi-literate Bedouin across eastern Arabia, and now much cherished by an X Factor-style annual television competition called Million’s Poet, which is screened across the Gulf. The work of Hissa Hilal, a veiled Saudi Arabian woman and mother of four, who reached the final of the 2010 edition of the show with her nabati poem “Against Extremism,” is another good place to start.

The scholar Steven Caton, who had recorded zawamil in the obscure highland villages of northern Yemen in the 1980s, was astonished to hear them chanted thirty years later by tens of thousands of demonstrators when the Arab Spring engulfed the country in 2011.

The Houthi, whose war poetry has recently gone global, were part of an alliance of popular forces brought together in opposition to the corrupt governance of president (and ex-general) Ali Abdullah Saleh. They had first emerged as an organized movement in their home city of Sa’da in 1992, defending their own Shiite traditions from the aggressive preaching of Wahhabi Sunni missionaries from neighboring Saudi Arabia. In 2004 their leader, Hussein al-Houthi, was killed and 800 of his followers were imprisoned by the government, igniting armed resistance in their mountain homeland in the north-west, which continued over the next six years (from 2004 to 2010) under the leadership of his brothers.

So the al-Houthi had every good reason to join the protest marches of the Arab Spring in 2011, which by 2014 had evolved into a three-cornered civil war, with the remnants of the corrupt old regime propped up by an aggressive Saudi-Gulf military coalition. This civil war raged from 2015 to 2022. For seven years the Houthi, under the leadership of Abdul-Malik Badruldeen al-Houthi endured air strikes, drone attacks, naval blockades and marine landings, but now and then managed to lob a rocket at targets in Saudi Arabia and the Emirates. The whole country suffered, with 150,000 Yemeni killed in the war, and an additional 230,000 dying through associated famine and disease, before a temporary truce called a halt to hostilities in 2022.

To survive against the extravagantly funded armies of their oil-rich enemies, the al-Houthi have transformed northern Yemen into a militant regime and allied themselves with the Iranian “Axis of Resistance.” Their poetry is the most successful part of their propaganda which stresses their piety, bravery, learning and poverty compared with the corruption, wealth, laziness and hypocrisy of their enemies, whom they portray as betraying their fellow Arabs with their open alliance with Israel, the USA and UK, and liken to Yazid, a hated caliph from the seventh century. Memories are long in the Islamic world, and the Houthi poetry contains constant references to the great Shia heroes — to the example of Imam Ali and the martyrdom of Husayn at Karbala — for it is part of the Shia tragedy that in every generation, the good suffer.

Poetry is the most successful part of Houthi propaganda which stresses their piety and bravery

The al-Houthi follow a very mild version of the Shia faith, first brought to Yemen by their ancestor, Yahya ibn al-Husayn, who was buried beside an old mosque in the ancient city of Sa’da in 911 AD. A direct descendant of Mohammed, Yahya followed the teachings of his own saintly grandfather, who was emphatic that to rule with injustice and oppression is a heresy of Islam, and that it is the duty of all true believers to remove themselves from such injustice.

He taught that a true leader of the Muslims should be chosen from the many descendants of the prophet, identifiable by his possession of fourteen virtues, which start with piety, bravery, learning and poverty. This ideal leader — the “guide to the truth” — is acclaimed by the zamil poets.

Tanks, jets, drones and rockets are no more than visual backdrops to the still provincial, rural identity of the poetry, with its traditions of poverty and faith. Resembling a fusion of the redneck hillbilly populist sentiments of the Appalachian Mountains and the spirit of a Highland Jacobite chieftain from the pages of Robert Louis Stevenson, the Houthis’ ongoing disruption of Red Sea shipping has brought the millennia-long poetic traditions of the Arabian peninsula to our attention.

Barnaby Rogerson’s The House Divided: Sunni, Shia and the Making of the Middle East is out now. This article was originally published in The Spectator’s UK magazine. Subscribe to the World edition here.

Leave a Reply