“He walked as calamity. He walked under Libra. He was living all this bullshit from the inside out. Oh, he scathed himself and harangued and to his own feet flung down fresh charges. But there were dreams of escape, too — one day you could ride south on a fine horse for the Monida Pass.” Well met by moonlight, Tom Rourke, doper and dreamer, formerly of County Cork, now a miner in Butte, Montana, in 1891. Welcome to yet another wild and whirling world made by Kevin Barry.

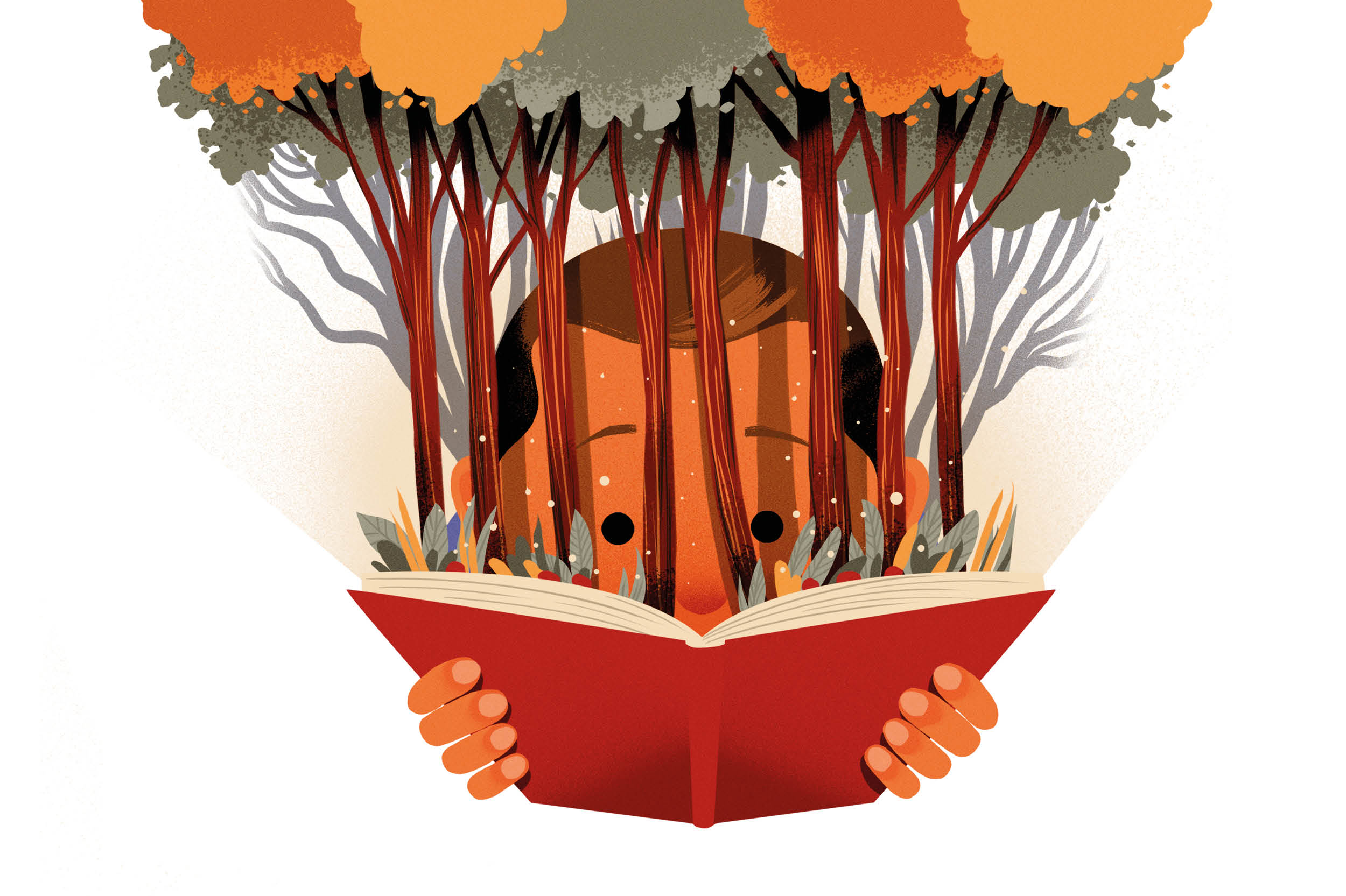

Barry’s first collection of short stories, There Are Little Kingdoms, appeared in 2007; he was already celebrated in his native Ireland as a creator of darkly comic troubled characters compassionately drawn. The publication of “Fjord of Killary” in the New Yorker in January 2010 marked his arrival on an international stage as a fiction writer of immense promise. Barry’s first novel, 2011’s City of Bohane, set in a not-far-distant future (that manages also to be archaic) in a mob-controlled town in the west of Ireland, and boasting characters like Jenni Ching and Fucker Burke with their own individual voices, fetishes, madnesses and desires, had critics and writers from Irvine Welsh to Pete Hamill — in his glowing review for the New York Times — comparing Barry to Joyce, and Bohane to Ulysses. An apter comparison would be Ulysses via A Clockwork Orange, for Barry is more comfortable than Joyce with both a polyglossia of argots and the old ultraviolence. Such comparisons would be a heavy weight for any writer to carry, but Barry’s borne it well for over a decade. His three short story collections and three novels have received immense acclaim and won substantial prizes. Barry and his wife Olivia Smith have also been the editors and publishers of Winter Papers, a rich, deep annual arts anthology, since 2016. When, you wonder, does the man sleep?

Barry, unlike Joyce, has not been overtly autobiographical in his writing to date, from the searing Bohane, with its naturalistic characters “gobblin’ hoss trankillisers like they’s penny fuckin’ sweets” to the psychological chaos of 2015’s Beatlebone, a broken series of revolutions around John Lennon’s 1978 trip and head-trip to Dorinish, an island off the County Mayo coast Lennon had bought in 1967. Unlike Joyce, Barry doesn’t confine himself to stories set in or about Ireland. His last novel, 2019’s splendid, scary Night Boat to Tangier lets you know from its title where the two old drug smugglers — admittedly Irish, yes — are putatively heading. Though Barry continues to live in County Sligo, in recent years he’s been spending time in North America, from Montreal and Toronto to Los Angeles, and now he’s set his sights on Butte.

The Wild Wild West is the perfect setting for Barry’s abilities and agilities. The Heart in Winter is under 300 pages long, but in no way is it slight. It is a rambunctious galumph of a story, a saga, yet somehow sparely, cleanly told, a slim volume bursting with energy, history, possibility, brutality and poetry. Irishmen figure prominently in the novel, appropriately enough. The city ports of Boston and New York were flooded with Irish immigrants from the late 1840s, and after many boys and men went to fight for Lincoln and the Union Army, they heeded that supposed directive of Horace Greeley’s to go West. Navigators built the new cross-country railroads and died by the thousands from cholera and other plagues; other Irishmen and first-generation Irish Americans went down into the dark dungeons in the earth, from the Appalachian coal mines to the hard rock mineral mines of Montana. A fast-aging boy named Tom Rourke, hero of The Heart in Winter, is one of the latter.

How is it that Barry manages to write an utterly original novel that is so steeped in American history and actual accounts of the American West, as well as its fictions in writing and on film? As I got to know Tom Rourke, memories kicked aside the swinging saloon doors in the recesses of my mind, happily emerging to complement Barry’s story. Threads of past tales of the West, in stories and songs and movies, are powerful in this novel: loners like Alan Ladd, Gary Cooper and Clint Eastwood; young Sean O’Brien dying of snakebite crossing a muddy flooding river in Lonesome Dove; Butch Cassidy, the Sundance Kid and Etta Place on the run; the teenaged lovers of Annie Proulx’s “Them Old Cowboy Songs,” in their rickety little cabin on the lone prairie. The arrival of a palomino mare put me in mind of Willie Nelson’s red-headed stranger from Blue Rock, Montana, who loves his dancing bay pony far more than he’ll ever love any woman living. Real stories are Western tales, too; and Mari Sandoz and Old Jules, the Wilder girls, the Donner party, Lewis and Clark and Sacagawea all were rich in my mind once again, when I finished this novel. My own recollections and imagination were enabled, encouraged, by Barry’s seductive rush of language and riveting telling of a tale. This is a writer for whom to be always grateful.

Trotting through the book you experience vivid hallucinations, natural phenomena, religious mania, jealous rage, pure cruelty and selfless love. You learn many new words, some resurrected from the 1890s, some nineteenth-century Irish slang, some Barry-made. Use them yourselves now: gowl, loolah, thorn-bled, hatchwork, godhaunts, hooktip. They’re on every page and seamlessly so, increasing rather than trammeling your understanding — and pleasure.

Tom Rourke is not just a bard in search of a muse, a boy in search of a girl and something of a dandy, fueled in what he undertakes by opium, peyote, rotgut hooch and/or an overwhelming desperate love: “He wore the felt slouch hat at a wistful angle and the reefer jacket of mossgreen tweed and a black canvas shirt and in his eyes dimly gleaming the lyric poetry of an early grave and he was satisfied with the inspection.” He is also a writer, something new for a major Barry character. As The Heart in Winter begins, Rourke is writing a letter for his mate Holohan to land him a mail-order bride, coming west from Boston. This is a part of the “westward movement” little discussed in histories until fairly recently, but it happened. Hollywood knew about it — who can forget Grace Kelly as Amy Fowler, arriving in that dusty desert town to become Mrs. Sheriff Kane?

Rourke crafts the letter carefully, and as we see many pages later, successfully: “He had it within himself to help others. He made no more than his dope and drink money from it. He had helped to marry off some wretched cases already. The halt and the lame, the mute and the hare-lipped, the wall-eyed men who heard voices in the night — they could all be brought up nicely enough against the white field of the page. Discretion, imagination and the careful edit were all that was required.” Just look at the power of fiction to create, transform, cheat and lie. Barry knows it all better than any living novelist.

The small vignettes and scenes that light up the world of Butte and the endless wilderness around it are terrific. Witness one Con Sullivan, or Fat Con, behind the counter of his “eatinghouse” on a Sunday morn: “He cut white loaves on the slicer and chopped the liver into neat hanks with a murderer’s relish. He was a man in his time. He was alive to his place and task. He swung his great belly from grill to counter and back again and there was grace to it. Dankly his occult coffee simmered and there were canteen pots of tay stewed black as porter. Dead bloodshot eyes sat in a row for him along the high stools and every last set of them was beholden.” And another man, bereft, disappointed in love, who “hated especially the eloquent. Words dropped from his own lips like stones. He could put not warmth nor humor in them. It was not that he did not feel such things. He had been lonely in his life always but never before heartbroken.”

Rourke has a Gypsy-Davy charm, and it appeals not only to readers, but to the new youngish wife of an old man. The story is timeworn but always resonant, especially when the wife is as sassy and resilient as is Polly Gillespie. Not just to survive but to thrive: how to do it, if you’re a young couple, in a wild dirty town on the fringe of what’s called civilized? How to do it on the run through the nowhere woods, into the unmapped, with a sheriff and a pack of Cornishmen, far from their native sea but as mean as the worst pirates and led by a giant named Jago, on your trail? The Heart in Winter is a quest, a chase, a ballad, a love story, a Western, a magic gritting romp that as it goes gets only more compelling, in the skipping reels of its telling.

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s July 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply