Four-star Marine General Kenneth “Frank” McKenzie headed US Central Command — CENTCOM, covering the Middle East — from spring 2019 until spring 2022. It was an eventful, and stressful, three years: taking out long-time Islamic State head Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi in 2019, then notorious Iranian Quds Force commander Qasem Soleimani in early 2020 and overseeing the disastrous final withdrawal from Afghanistan in 2021.

Prior to CENTCOM, McKenzie had spent four years in two top-level Joint Chiefs staff posts, and before that he served multiple tours of duty on the ground in Afghanistan. As a younger officer he had been in the Pentagon on September 11, 2001, when American Airlines Flight 77 hit; he was commissioned in the Marine Corps right out of the Citadel in 1979. He credits his English courses there for teaching him that “I could write and write well,” and this fast-paced, hugely impressive analytical account of his service years demonstrates the truth of that observation page after page.

Given McKenzie’s years at CENTCOM, The Melting Point is also essential reading for anyone interested in what Donald Trump 2.0 might mean for the world come January 2025. While recounting White House meetings, McKenzie time and again refers to “the president,” rather than specifying either Trump or Joe Biden, an implicit reflection of McKenzie’s deep devotion to the US tradition of civilian control of the military.

Yet while The Melting Point is always polite and measured, McKenzie never shies from bluntly calling out what he sees as a tragically long series of US blunders in the Middle East. To McKenzie, “the single greatest missed opportunity of the campaign on the military side” occurred all the way back in 2001, just months after 9/11, when “the CENTCOM commander” — McKenzie does not call out General Tommy Franks by name — “would not release the forces necessary” to kill Osama bin Laden in the Tora Bora mountains. But George W. Bush’s White House instigated a far graver error, says McKenzie; “invading Iraq is appropriately viewed as one of the most disastrous and negatively consequential foreign policy decisions ever taken” by US leadership.

McKenzie is likewise harsh when it comes to President Barack Obama, noting unsurprisingly that “the passage of time has not been kind to the decisions made by the Obama administration.” For one thing, “Obama’s decision to surge forces into Afghanistan in 2010 while also setting a firm timeline for ending those operations… completely destroyed the strategic utility of adding forces in the first place and gave a lifeline to the Taliban,” the insurgent reactionary movement that had long sheltered bin Laden. Similarly wrong-headed, McKenzie writes, was the “Obama administration’s precipitous decision to withdraw from Iraq in 2011.”

But The Melting Point’s firm focus is on McKenzie’s own three years at CENTCOM. “One of my first acts after assuming command in March 2019 was… to ask if we held any plans to strike Soleimani”; McKenzie wanted “a relentless focus on Iran” and the dangers its allied militia groups throughout the region posed to US forces. Nine months later a missile attack killed an American contractor at Kirkuk in Iraq. “This was a game-changer, and it was obvious to me that we would be responding.” Two days later Joint Chiefs chairman General Mark Milley informed McKenzie “that we were to strike Soleimani in Iraq if he came there” per a decisive policy shift ordered by President Trump. McKenzie was quietly exhilarated; he “had watched the Obama administration national security apparatus” — and before that Bush’s — “grapple ineptly with the dynamism and leadership that Soleimani brought to the fight.”

Late on January 2, 2020 at CENTCOM headquarters at MacDill Air Force Base, McKenzie watched a live video feed as “a great flash of white arced across the screen,” marking the end of Qasem Soleimani’s life on an access road near Baghdad Internatio al Airport. “For me personally, as a Marine,” that moment was “profoundly satisfying on a deep, emotional level” — Soleimani “had the blood of hundreds of US servicemembers on his hands, and he had been plotting to kill more,” McKenzie writes. He also knew that Iranian retaliation would not be long in coming, and “for the first time in the history of warfare, US forces were subjected to ballistic missile attacks” at a base in Iraq, but no fatalities ensued. “In a wise and far-sighted decision, the president chose not to respond to the Iranian attack.”

McKenzie is likewise quietly commendatory of Trump’s demeanor when the earlier decision had been made to target Baghdadi: the president “was focused, and asked good questions,” he observes, pushing back on the widespread assumption that Trump was an emotionally deranged chief executive. Yet McKenzie harshly criticizes his administration’s February 2020 agreement to withdraw all US forces from Afghanistan by mid-2021, even though at the time McKenzie himself endorsed the accord. “Setting a date was an enormous strategic mistake that gave renewed life to the Taliban, even as it deflated the government of Afghanistan. We also agreed to stop air strikes against the Taliban,” he reflects. “These two decisions represent some of the worst negotiating mistakes ever made by the United States” and were “purely a reflection of our desire to have an agreement at any cost.”

But McKenzie appreciates how the US presence had become a tragic error. “We forgot why we were there. We entered Afghanistan to remove the source of an attack on our homeland and to prevent future attacks. This morphed into an exercise in nation-building,” albeit one “where we never achieved the most fundamental condition necessary for counterinsurgency success,” namely cutting off the Taliban’s sanctuary in neighboring Pakistan. This represented “a policy failure at the highest level of our government across multiple presidential administrations.” Even more fundamentally, “it was a remarkable exercise in American arrogance to believe that we could create a democratic society in Afghanistan.”

McKenzie recounts in detail a June 2, 2020 White House meeting about drawing down US troop levels prior to full withdrawal. Donald Trump “was engaged and interactive from the beginning,” and “was very measured as he asked questions.” Trump spoke “about all of the money that had been poured into Afghanistan — and with so little effect,” and “it was difficult to disagree with him.” McKenzie knew then “that a complete withdrawal would likely lead to a rapid collapse of the Afghan security forces and the government,” so he and General Milley strongly favored retaining a minimal US presence for as long as possible.

Come November, Trump lost reelection and soon thereafter fired superb defense secretary Mark Esper, leaving a small cast of amateur misfits as the Pentagon’s top civilians. Milley and McKenzie feared that Trump’s lame-duck cast of characters might provoke the president to attack Iran, but at a December 4 White House meeting “it was the president who resisted these more aggressive approaches,” McKenzie recounts. Trump “was engaged, focused and quite interested in both the large concepts and the small details” that his uniformed commanders laid out concerning Iran. “I found the president to be rational and very reasonable.”

Nonetheless, McKenzie strikingly states that “simply arriving at the afternoon of January 20 without a major war with Iran underway was a great accomplishment.” Yet he was far from overjoyed with the exceptionally remote new defense secretary, former general Lloyd Austin, or with President Biden. McKenzie compares April 11, 2021, when Milley informed him that Biden had ordered a total US withdrawal from Afghanistan by the end of August, with the emotional impact of 9/11. “To withdraw while still maintaining an embassy… and not undertaking a withdrawal of American citizens and at-risk Afghans concurrently” was a calamitous decision that “was entirely his” and that “irrevocably accelerated the trajectory” of the inevitable Afghan collapse.

Come August, events on the ground indeed proved that “it was impossible to achieve success with the decision that was made.” As the Taliban advanced on the city, it made the ill-considered decision to free hundreds of Islamic State fighters from prisons, including one who on August 26 successfully mounted a suicide attack on the US troops who were providing security for the hurried and chaotic mass evacuation underway at Kabul’s international airport.

“The attack was not preventable by the forces on the ground unless we stopped bringing evacuees inside the perimeter,” McKenzie grimly observes, and the deaths of thirteen US service members “will haunt me for the rest of my life.” Nonetheless, “on the day of the attack, we brought out a total of 13,390 people. I consider that number any time I reflect on the loss of those thirteen brave Americans. I do not believe that their deaths were in vain.”

All in all, “our withdrawal from Afghanistan was a huge victory for international terrorism,” McKenzie admits, and “the return of the Afghanistan platform for terrorists will prove increasingly problematic for us over time,” he predicts.

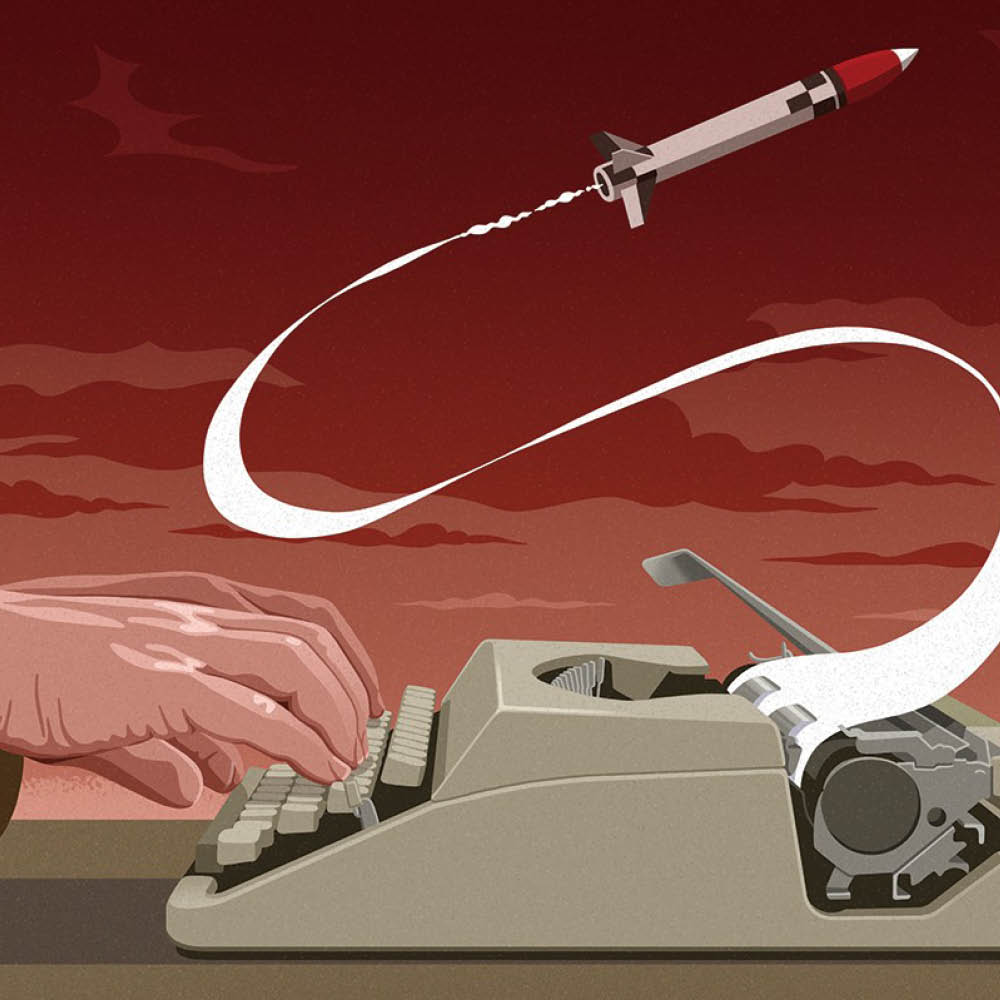

Yet terrorism is far from McKenzie’s most dire fear. “Nuclear weapons are coming back as battlefield weapons,” he cautions, and “I am convinced that the next large war we fight will have a nuclear component.” What’s worse, “modern missiles… have made the great oceans that border the North American continent little more than river barriers,” he writes memorably. “The next war… will be bloodier than what we have come to expect,” and “other nations” — plural — “are assiduously preparing for this war, and… are targeting us.”

General McKenzie’s fine memoir is a rich and powerful testament to the qualities that our best military commanders bring to their service to the nation. It is also, to use Thomas Jefferson’s famous phrase from two centuries ago, a fire bell in the night. The United States needs to be ready for “when war comes,” McKenzie warns, for “it’s coming faster than we realize.”

This article was originally published in The Spectator’s August 2024 World edition.

Leave a Reply